内容简介

Shelter and natural light are fundamental elements of architecture. The first is concerned with protection from natural elements; the second with the creative and sometimes spiritual interaction between the man-made and the natural worlds. One is solid and static, the other illuminates and animates.

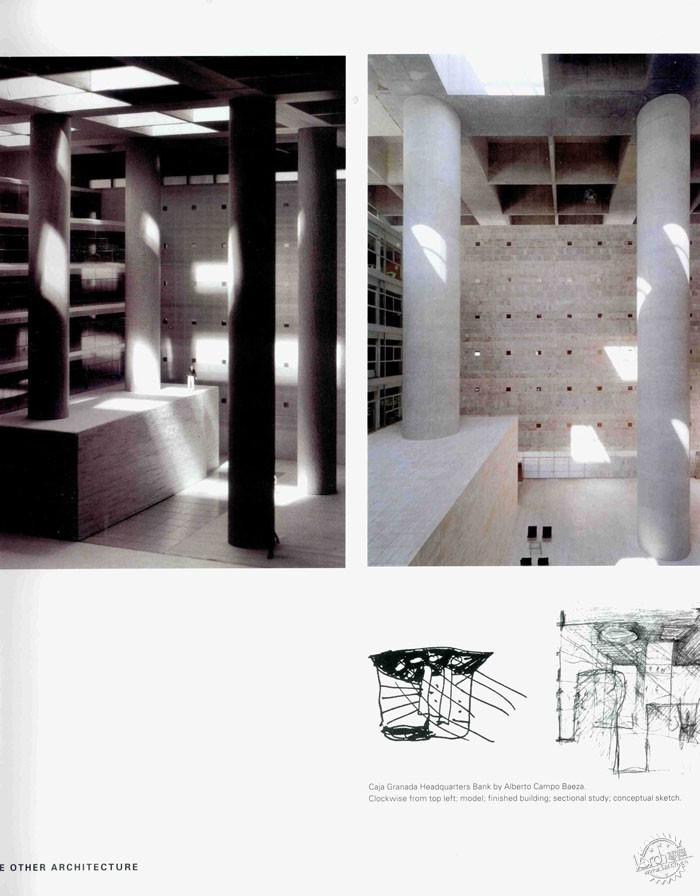

Architects through the ages have preoccupied themselves with how to marry these two opposing aspects of architecture, a marriage that at its finest transforms natural light itself into a building material. Seen through the eyes of an architect and photographer, The Architecture of Natural Light is the first publication to consider the many effects of natural illumination in contemporary buildings. This comprehensive and thoughtful survey begins with a brief introduction exploring the advances and experimentation of architects throughout the centuries. Each of the following seven chapters is devoted to a specific quality of natural light, including evanescence, atomization, and luminescence, and examines the particular uses of light through many disciplines—from art history to film and literature. With more than fifty case studies of buildings from around the world, this volume considers works by some of the world’s most influential architects, including Tadao Ando, Steven Holl, Herzog & de Meuron, Peter Zumthor, Frank Gehry, álvaro Siza, Alberto Campo Baeza, Rafael Moneo, Rem Koolhaas, Jean Nouvel, Fumihiko Maki, and Toyo Ito, among others.

For all those seeking to create space that transcends the physical, The Architecture of Natural Light is a powerful and poetic yet practical survey that provides an original and timeless approach to contemporary architecture.

作者简介

Henry Plummer teaches architectural theory and design at the University of Illinois, and is an associate of the Center for Advanced Study there. He received his M.Arch. from M.I.T., studied light art with Gyorgy Kepes, and was a photographic apprentice to Minor White. He is the author of numerous books, most recently Masters of Light, First Volume: Twentieth-Century Pioneers.

目录

The Other Architecture

Constructing metaphysical space

1

Evanescence

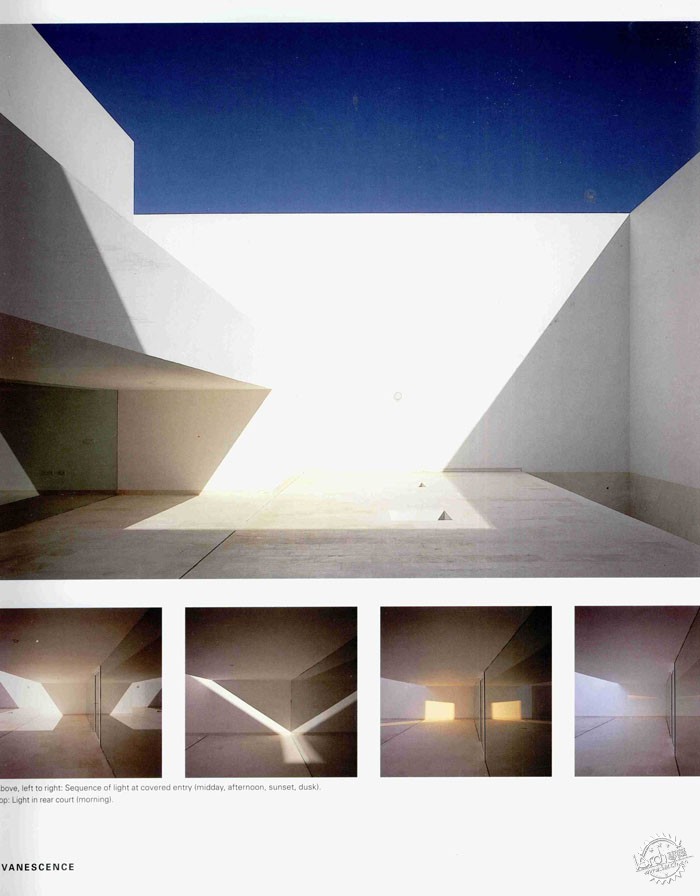

Orchestration of light to mutate through time

2

Procession

Choreography of light for the moving eye

3

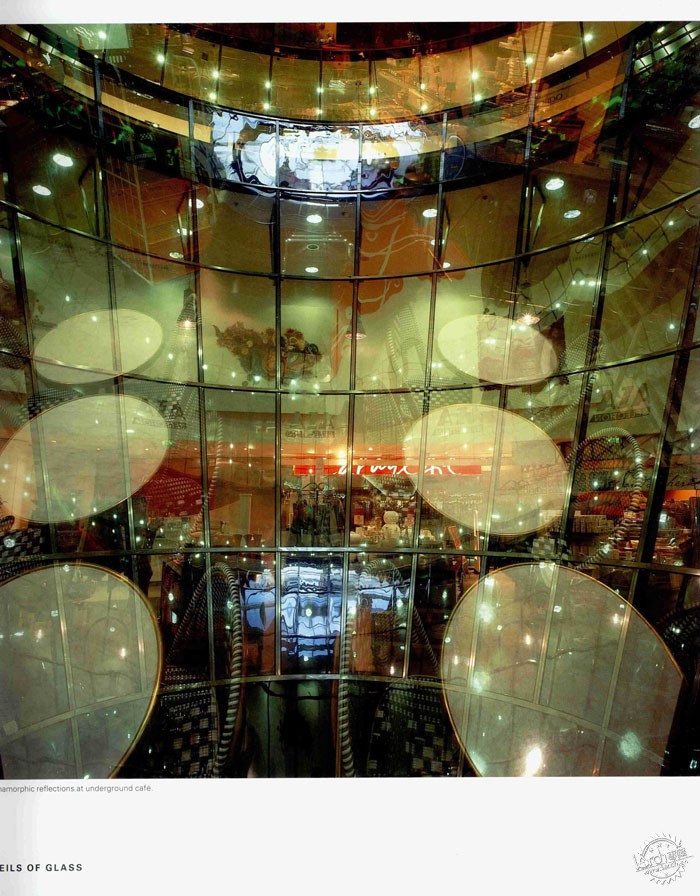

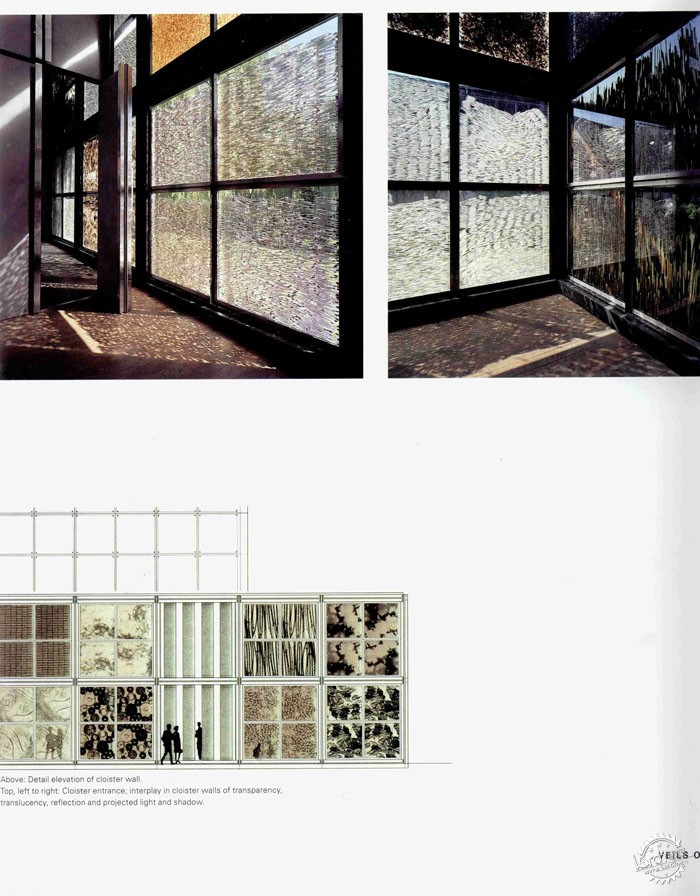

Veils of Glass

Refraction of light in a diaphanous film

4

Atomization

Sifting of light through a porous screen

5

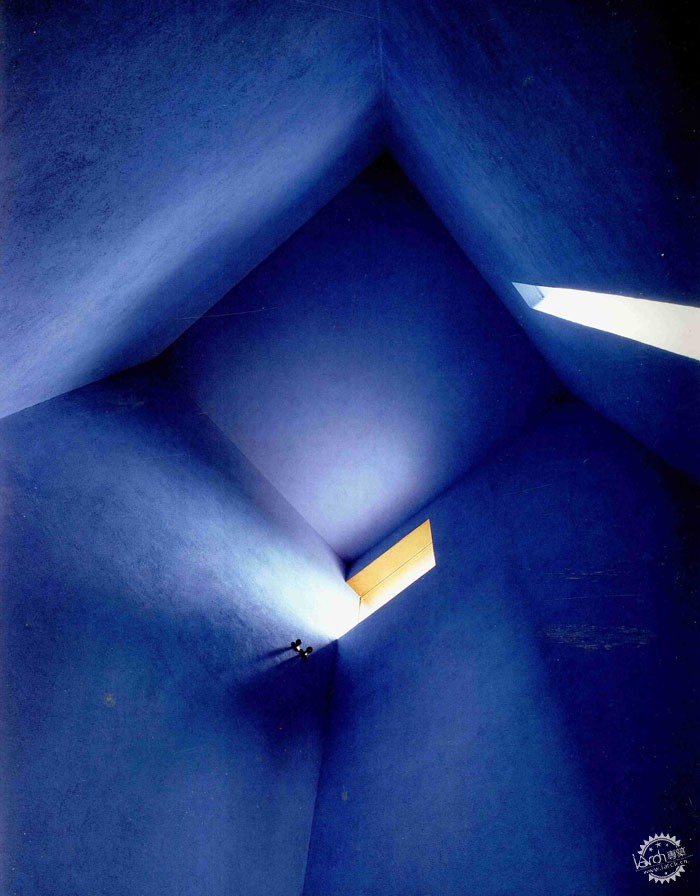

Canalization

Channelling of light through a hollow mass

6

Atmospheric Silence

Suffusion of light with a unified mood

7

Luminescence

Materialization of light in physical matter

Sources

文摘

From: Introduction

The Other Architecture

Constructing metaphysical space

The beholding of the light is itself a more excellent and a fairer thing than all the uses of it.—Francis Bacon (1561–1626)

The ebb and flow of light in the sky affects every part of our lives, and literally makes possible life on Earth. At its simplest, light allows us to see, to know where we are and what lies around us. Beyond exposing things to view, light models those things to enhance visual acuity and to help us negotiate the physical world. Furthermore, daylight is the source of energy that drives the growth and activity of all living things, and over millennia has waxed and waned with such intensity that our bodies and minds are now closely tuned to its cycles and spectrum. In addition to generating life, daylight is also essential to sustaining life by deterring a large number of diseases, as well as maintaining our biological rhythms and hormonal distribution. While we have invented many kinds of artificial light to supplement the light of the sun, the radiation of such man-made alternatives lacks the tempo and wavelength, nuance and tone necessary to replace our need for frequent exposure to natural light.

These practical virtues have impelled builders to open their forms to available light, within varying constraints of climate and culture. But while infusions of daylight may ensure that the lighting in buildings is adequate and comfortable, we need more from architecture than physical contentment. We expect our buildings to also be emotionally satisfying: to appear alive rather than dead; to take hold of our affections with moods that resonate with what we wish to feel inside; to keep us in touch with the flow of nature; and to empower us to make spaces our own by activating our perceptions and dreams. These extra depths of experience imply aspects of light that may have no practical benefit whatsoever, beyond satisfying the human spirit.

From the beginnings of architecture and all over the world, man’s relationship with light has transcended necessity, and even the limits of objective reality. The way daylight has been handled historically by architects offers striking insights into the human ethos of each age, and often tells a tale that is different from the more rational language of form and space. The most remarkable of these constructs are religious in nature, where light was employed to arouse feelings of mysticism and to convey the sacredness of a place. Commonly identified with spiritual forces and beings due to its awing powers over life on Earth, light could manifest a divine presence for believers. But also expressed in such buildings was something simpler and more immediately graspable: an ethereal presence at the outer limits of material existence with a miraculous capacity to bring things alive at a sensory level, and to create, before one’s very eyes, a sudden intensity of being.

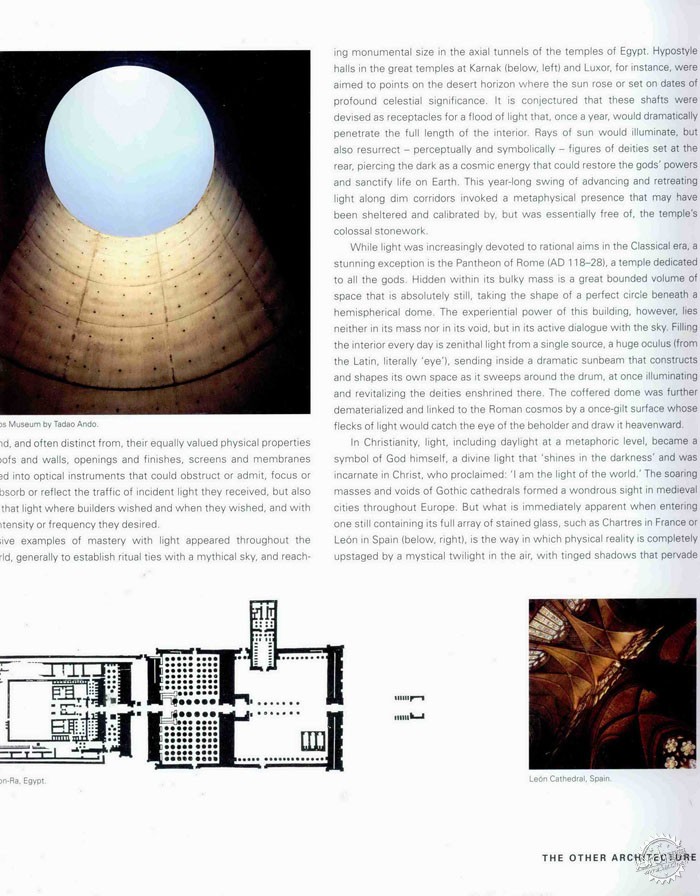

Even the most cursory account of changing attitudes towards daylight and architecture reveals dramatic variations in the meaning and handling of light itself, and in its capacity to visualize a wide range of beliefs and values that could not be expressed with material form. Therein lay an extraordinary challenge for architects, for how could they creatively manage the sea of light found in the air when that radiation could not be grasped or worked with the hands? One cannot even see light unless it is aimed directly into the human eye, or arrives after striking a solid object or filtering through a medium, such as smoke or mist. To overcome this predicament, builders resorted to modulation, inventing a repertoire of light-controlling elements that behaved in ways beyond, and often distinct from, their equally valued physical properties. Roofs and walls, openings and finishes, screens and membranes were shaped into optical instruments that could obstruct or admit, focus or disperse, absorb or reflect the traffic of incident light they received, but also could send that light where builders wished and when they wished, and with whatever intensity or frequency they desired.

Impressive examples of mastery with light appeared throughout the ancient world, generally to establish ritual ties with a mythical sky, and reaching monumental size in the axial tunnels of the temples of Egypt. Hypostyle halls in the great temples at Karnak and Luxor, for instance, were aimed to points on the desert horizon where the sun rose or set on dates of profound celestial significance. It is conjectured that these shafts were devised as receptacles for a flood of light that, once a year, would dramatically penetrate the full length of the interior. Rays of sun would illuminate, but also resurrect – perceptually and symbolically – figures of deities set at the rear, piercing the dark as a cosmic energy that could restore the gods’ powers and sanctify life on Earth. This year-long swing of advancing and retreating light along dim corridors invoked a metaphysical presence that may have been sheltered and calibrated by, but was essentially free of, the temple’s colossal stonework.

下载百度网盘链接:http://pan.baidu.com/s/1dEb6tRr |

|