德绍包豪斯校舍/Bauhaus Dessau © Nate Robert via Flickr License Under CC BY-SA 2.0. Image

包豪斯女性艺术家的那些历史故事

The Lost History of the Women of the Bauhaus

由专筑网李韧,蒋晖编译

格罗皮乌斯(Walter Gropius )于1919年成立了包豪斯学校,这是一个开放的场所,“无论年龄与性别,任何盛誉良好的人,”都能在这里感受到“没有差异的气息”。这样的一个理念诞生在这个时期是非常特殊的,因为在当时女性需要涉及某些领域时,仍然是需要进行申请的。但如果女性想要接受艺术教育,则依旧无法进入公立学校学习。但是在包豪斯,格罗皮乌斯的观点得到了广泛的认可,因此这里的女性学生比男性还要多。

When Walter Gropius created his renowned school of design and arts in 1919, he devised it as a place open to "any person of good reputation, regardless of age or sex," a space where there would be "no differences between the fairer sex and the stronger sex." His idea occurred in a period when women still had to ask permission to enter fields that were once off-limits. If women received an artistic education, it was imparted within the intimacy of their home. But at the Bauhaus and the Gropius school, they were welcome and their registration was accepted. Gropius' idea was so well-received that more women applied than men.

瓦尔特·格罗皮乌斯/Walter Gropius © via Wikimedia License Under Public Domain. Image

然而,格罗皮乌斯的性别平等理念似乎并没有完全实现。在建筑、绘画、雕塑领域,似乎仍然存在着性别优势,尽管“性别平等”这样的观点在其他某些学科中得到体现,但在这些学科的创始人看来并非如此。

那这是为什么呢?根据格罗皮乌斯的说法,女性在身体与心理上并不那么适合于学习艺术,因为她们的思考方式往往停留在二维空间,而男性则能够更好地进行三维空间的思考。

因此,那些出自于包豪斯学校的知名人士,例如Paul Klee、Wassily Kandinsky、László Moholy-Nagy、Ludwig Mies van der Rohe,他们的许多合作伙伴已经销声匿迹,亦或是成为了他们妻子。

在密斯担任包豪斯学校的校长期间,即20世纪30年代,整个学校的男性化趋势愈发明显。密斯的教学主要面向建筑与金属专业,这个领域曾经禁止女性涉及。

However, Gropius' declaration of gender equality never realized in the way he initially professed. Architecture, painting, and sculpture were reserved for the "stronger sex," while the "fairer sex" was offered other disciplines that were not, in the founder's opinion, so physical.

Why? According to Walter Gropius, women were not physically and genetically qualified for certain arts because they thought in two dimensions, compared to their male partners, who could think in three.

Thus, it was the men of the Bauhaus who have gone down in history, figures like Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, László Moholy-Nagy, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, while their colleagues have been forgotten or, in the best of cases, are recognized as "the wives of."

This masculinization of the Bauhaus became more evident in the early 1930s during Mies van der Rohe's period as director. His teachings were oriented mainly towards architecture and metal works, a field women had previously been barred from.

巴塞罗那椅/Poltrona Barcelona © Vicens via Wikimedia License Under CC BY-SA 2.5. Image

但Lilly Reich似乎并不认同,这位来自德国的设计师与建筑师是密斯的亲密合作伙伴。其合作关系长达12年之久,而Reich并没有学习过建筑,但是她进行过其他艺术学科的学习,例如设计,因此她的职业生涯开始于工业设计与服装设计方面。

她和密斯共同合作的项目有德意志制造联盟展廊建筑、柏林“Velvet and Silk Cafe”展馆,还有众所周知的1929年巴塞罗那世界博览会德国馆。另外,她还参与了包豪斯的两个项目,即图根德哈特住宅和朗格住宅。

后来密斯成为包豪斯的校长,他邀请Reich在德绍创办一间工作坊,另外他还让Reich担任纺织设计工作坊的主要负责人,因此她在德绍和柏林都有工作职位。Reich也因此成为了在包豪斯这两个校区中共同任职的极少数的教育家。

1937年,密斯移民去往美国,他们长期的合作关系就此结束。Reich负责管理建筑工作室、商业项目,以及家庭事务。1939年,Reich来到美国,他们又进行了短期的合作,即位于芝加哥的ITT项目。当时,Reich希望能够留在这里,但是密斯似乎不太同意,因此Reich在二战期间回到了德国。

后来他们再也没有相见,只是通过书信联系。战争结束时,Reich在柏林大学教授室内设计与建筑设计理论。再后来,Reich在柏林开设了自己的建筑设计工作室,她一直致力于设计工作,直至1947年逝世。

Lilly Reich职业生涯研究者兼Knoll设计管理人员Albert Pfeiffer认为,密斯的成功与Reich密切相关。

But Lilly Reich turned a deaf ear. The German designer and architect was a close collaborator and partner of Mies van der Rohe for more than 12 years. Reich never studied architecture, but she practiced it along with other artistic disciplines, such as design. It was that field, industrial and fashion design, that began Reich's career.

She and Mies van der Rohe worked together on various projects including the apartment building for the Deutscher Werkbund exhibition, the "Velvet and Silk Cafe" exhibition in Berlin, and the German pavilion for the 1929 Barcelona International Exposition. She also participated in two paramount works of Bauhaus architecture: the Tugendhat house and the Lange house.

When Mies van der Rohe was appointed director of the Bauhaus, he invited Reich to give a workshop at Dessau. He also named her director of the interior and fabric design workshop, a position she held simultaneously at both the Bauhaus in Dessau, and in Berlin. Reich thus became one of the few educators to teach at both schools.

Their partnership ended when he emigrated to the US in 1937. She took over the architect's studio, business, and family responsibilities. Their last collaboration was in 1939 when Reich moved to the US and participated with her former partner in the ITT project in Chicago. Reich wanted to stay, but Mies van der Rohe was not fond of the idea, so she returned to Germany in the middle of World War II.

They never saw each other again, although maintained an epistolary relationship until his death. At the end of the war, she taught interior design and building theory at the University of Berlin. In Berlin, she reopened her design and architecture studio where she worked until her death in 1947.

According to Albert Pfeiffer, the vice president of design and management at Knoll and a researcher of Lilly Reich, the success of the famous architect is closely correlated with the period of his relationship with Reich.

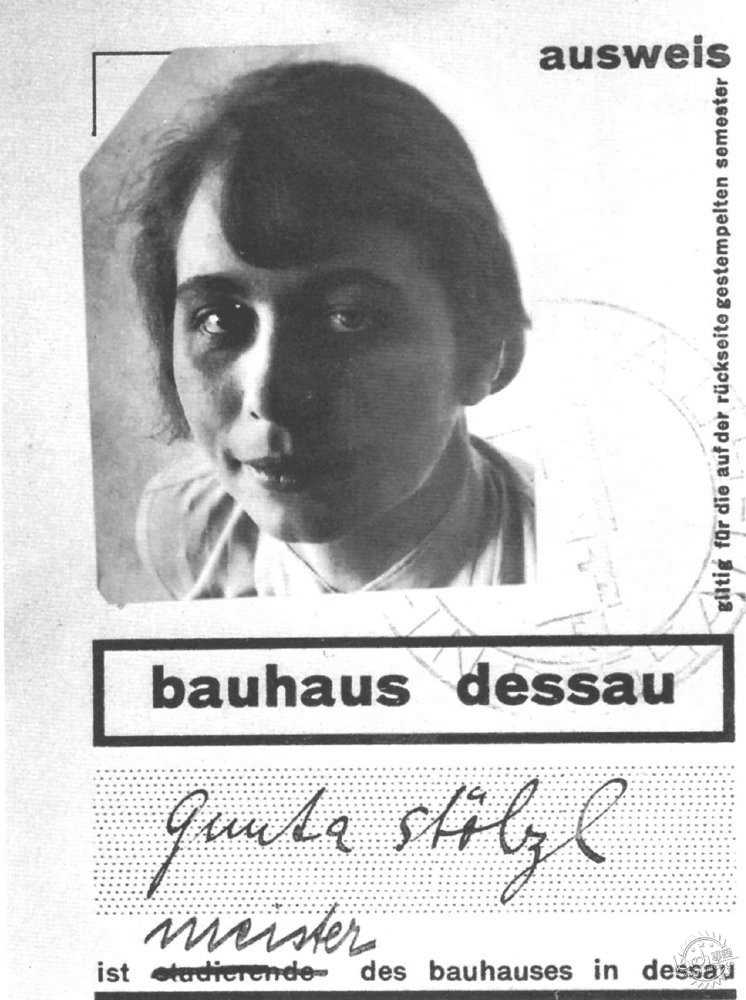

Gunta Stolz © Sascha Wagner via Wikimedia License Under Public Domain. Image

“这并非巧合,密斯的成功离不开Reich的协助。有趣的是,在离开Reich的帮助后,密斯再也没有设计出出色的现代家具了。”例如世界上知名的那两张椅子。

Reich并不是包豪斯唯一的成功女教师,Gunta Stölzl、安妮·艾尔伯斯(Anni Albers)、Otti Berger、玛丽安·布兰德(Marianne Brandt)、 Karla Grosch等知名人士都曾就职于包豪斯。但与Reich不同的是,她们曾经都是这里的学生。

"It is becoming more than a coincidence that Mies' involvement and success in exhibition design begin at the same time as his personal relationship with Reich. It is interesting to note that Mies has not developed any modern furniture successfully before or after his collaboration with Reich." Furthermore, two of the most famous chairs in the world was designed by the pair: the Barcelona and Brno.

She was not the only female teacher at the male-dominated institution. Gunta Stölzl, Anni Albers, Otti Berger, Marianne Brandt, and Karla Grosch all worked at the Bauhaus. But unlike Reich, all were former students.

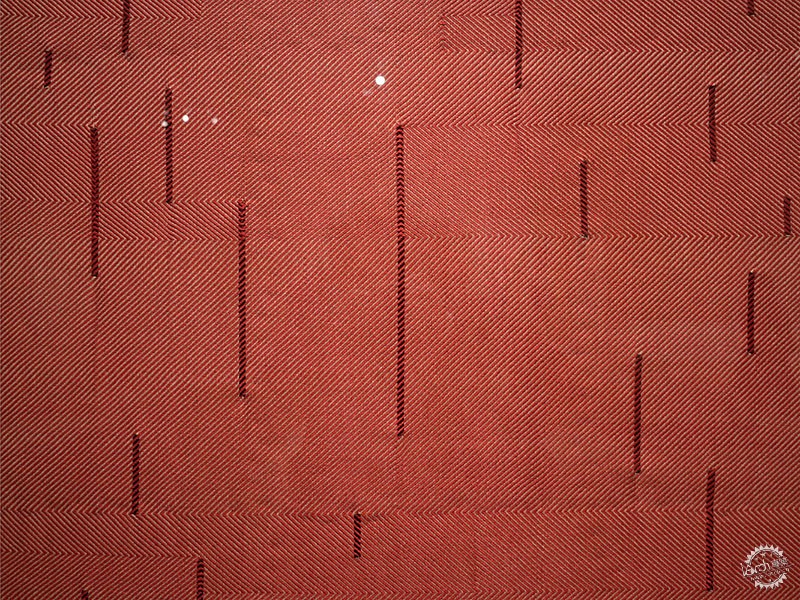

Cadeira com tapeçaria Gunta Stolzl © Sailko via Wikimedia License Under CC BY-SA 3.0. Image

Gunta Stölz既是包豪斯的学生,也是这里工作坊的老师,同时还是纺织工作坊的负责人,她是包豪斯唯一一位变幻了多重身份的女性员工。在这里,诸如建筑、雕塑、工业设计等热门专业的负责人大多为男性,而瓷器、编制艺术等专业则主要由女性设计师负责。格罗皮乌斯也正是通过这种策略来防止女性设计师的大量流失,从这个角度来说,他也为女性设计师保留了一席之地,而这一举措极具先见之明。

Stölz的个性十分明显,她认为格罗皮乌斯的“性别公平”理念也将成为包豪斯的一大特色。在其他项目中,她为德绍校区的Marcel Breuer进行了家具设计。然而,这位激进的右派学生在多次经受纳粹主义的打击后最终选择与一位犹太建筑师结婚。Stölz最终离开了包豪斯,前往瑞士,在那里她继续将自己的纺织设计事业发展下去,甚至还成立了自己的工作室。

Gunta Stölz was the only female teacher listed above who has worked in every position at the Bauhaus: a student, workshop teacher, and director of the textile workshop. As the other disciplines such as architecture, sculpture, and industrial design were reserved for men, ceramics and the art of weaving were exclusively for women. This was Gropius' strategy to stop the avalanche of female matriculants. Without knowing it, he was supplying the workshop with great female artists, that in the end, acquired great strength and acclaim.

Stölz was a woman of character who showed that the "fairer sex," as defined by Gropius, could also make a career at the Bauhaus. Among other projects, she designed furniture upholstery for Marcel Breuer at the school in Dessau. However, after being harassed by several, radical right students (at a time when Nazism was growing) for marrying a Jewish architect, Stölz left her post and the Bauhaus and moved to Switzerland. There she continued her career as a textile designer and established her studio.

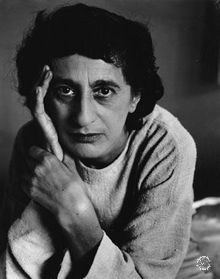

安妮·艾尔伯斯/Anni Albers © Gobonobo via Wikimedia License Under Fair Use. Image

安妮·艾尔伯斯(Anni Albers)极力推崇纺织品艺术与设计,如同其他许多人一样,她带着对绘画的渴望来到包豪斯,可是却只能在纺织品车间工作。这里的教育水平很高,Albers完成了所有的课程,并展示了自己独特的纺织与创新才能。在她的学术论文中,她设计了一种具有隔音、反射,同时可水洗的纺织物,这种纺织物由棉布与玻璃纸制作而成,主要用于剧场观众厅。

但是学校的政策并没有影响她在纺织品中的绘画,既然她不能在画纸上展示技艺,那么她就选择在各种织物中表达自己的绘画才能,其作品也因此而闻名。她的画作相对抽象一些,这与包豪斯的许多大师类似,比如康定斯基以及她未来的丈夫Josef Albers。

更为重要的是,她的老师Paul Klee对她产生了深刻的影响。Paul的绘画风格在其油画作品中表达得淋漓尽致。“当我看到他画的那些线条、细节,亦或是某个笔触时,我也努力在自己的作品中寻找到自己的特点。”这位艺术家在1968年的某次采访说说道。

Anni Albers这样描述包豪斯的哲学:“包豪斯最大的优点就在于这里没有明确的教学体系,所以一切都取决于你自己,你必须找到适合自己的工作方式,这种自由的感觉是每个学生都应当经历的。”

1933年,受到纳粹的影响,包豪斯学校就此关闭,Albers和丈夫去往欧洲旅行。在同一年的年底,他们接受建筑师兼纽约纽约现代艺术博物馆馆主的邀请,来到了美国,在美国北卡罗莱纳州的黑山学院任教,也正是在这里,Albers找到了适合自己的研究方式,同时她也开始为Knoll 和Rosenthal等公司进行纺织品设计。

在美国创立了自己的事业之后,这对夫妇继而在墨西哥、南美洲旅行,他们在挂毯和织物中表达了前哥伦布母题,这是他们旅行的重大成果。这位设计师对这些文化的技术与创作十分着迷,并且将这些内容在1965年的研究著作《On Weaving》中发表。

直到1994年去世之前,Albers始终都致力于纺织品艺术技艺的研究工作,同时她也是第一位在纽约当代艺术博物馆举办个人展览的女性纺织品艺术家。

就像Lilly Reich在建筑领域的成就一般,Marianne Brandt突破了女性研究领域的又一玻璃顶,那便是金属方向。Brandt所学广泛,她既是画家,也是雕塑家,同时还是工业设计师,在其晚年时候,她又热衷于摄影艺术。在魏玛美术学院时,她学习的是绘画和雕塑,后来进入包豪斯学校学习也许是她一生中最为重要的决定。同样地,由于学校政策原因,她无法进入绘画工作室学习,于是Brandt加入了Gunta Stölz的纺织品工作室。但她始终没有停止努力,后来她在由摄影师Hungarian和画家László Moholy-Nagy经营的金属工作室中获得了一席之地。Brandt 的作品给Moholy-Nagy留下了深刻的印象,因此毫不犹豫地让她留在了工作室中学习。在1928年,Brandt成为了Moholy-Nagy的接班人,负责管理这个工作室。

But if anyone elevated the art of loom and textile design, it was Anni Albers. Like many others, Albers entered the Bauhaus with the intention of training in painting, but the school's policy only allowed her to enter the textile workshop. Although the instruction given to the students was very practical, Albers finished the course demonstrating her ability to weave and innovate. For her senior thesis, she created a soundproof, reflective, and washable fabric made of cotton and cellophane tailored for a musical audience.

The school's policy didn't stop her from including painting in her textile works. If she was not allowed to show her art on a canvas, she turned her fabrics and tapestries (which she called hangings) into paintings. Her works are known for their picturesque fabrics, where abstraction takes prominence, just as it did in many of the great figures of the Bauhaus, such as Kandinsky and her future husband, Josef Albers.

But above all, she was influenced by the paintings of Paul Klee, her teacher, whose style she wanted to reflect on her canvases. "I watched what he did with a line, a point or a stroke of the brush, and I tried to some extent to find my own direction through my own material and artistic discipline," the artist explained in a 1968 interview.

Anni Albers described the philosophy of the Bauhaus: "What was most exciting about Bauhaus was that there was no teaching system yet in place. And you felt as if it depended only on you. You had to find your way of working in some way. That freedom is probably something essential that every student should experience."

When the Nazi party closed the school in 1933, Albers and her husband left the country to travel through Europe. Later that same year they traveled to the US, accepting an invitation of Philip Johnson, an architect and the curator of MoMA in New York. They were appointed to teach at the newly inaugurated experimental school Black Mountain College in North Carolina. It is in America where Albers found her space to experimenting freely, and where she started designing fabrics for companies like Knoll and Rosenthal.

Already established in the United States, the couple continued traveling through Mexico and South America. The result of these trips is the influence of the pre-Columbian motifs that are shown in some of their tapestries and fabrics. She became so immersed in the techniques and drawings of these cultures that she ended up publishing her research in the 1965 book entitled, "On Weaving."

Albers continued working on her designs and printing techniques until her death in 1994. She was the first woman textile artist to have a solo exhibition at the MoMA in New York.

Just as Lilly Reich managed to work in architecture despite being a woman, Marianne Brandt broke the glass ceiling in another discipline reserved for men: metal. Brandt was many things: a painter, sculptor, industrial designer, and at the end of her life, a photographer. She began her studies in painting and sculpture at the Weimar School of Fine Arts, but the most impactful decision of her life was to enter the Bauhaus. Initially, after being denied access to painting workshops, Brandt participated in the textile workshop under Gunta Stölz. But she did not stop until she received a position in the metal workshop run by the Hungarian photographer and painter László Moholy-Nagy. Moholy-Nagy was impressed by Brandt's work and did not hesitate to accept her into his workshop, despite the reluctance of many. She later replaced him as the director of the studio in 1928.

玛丽安·布兰德/Marianne Brandt © Mteuchert via Wikimedia License Under CC BY-SA 3.0. Image

布兰德在包豪斯的学习历经曲折。在工作中,布兰德以超高的水准进行产品生产,同时也将工厂经营得很好。但仅仅只在一年之后,她便离开了包豪斯。

在那个时候,玛丽安·布兰德(Marianne Brandt)已经设计了一些具有辨识度的日常用品,在其设计中有着明显的包豪斯风格,例如其典型的自由形式。Brandt常用三角形、圆柱体和球形,例如其在1924年设计的咖啡机MT50-55a、烟灰缸、茶壶MT49,还有大众所知的灯具Kandem 702。

Her passage through the Bauhaus was not easy. The fact that a woman was producing works at a high level and directing the factory did not sit well with her male counterparts. Unfortunately, after only a year she left her post and the Bauhaus.

By that time, Marianne Brandt had already designed some of the most recognizable, everyday objects. In all her designs, the stylistic footprint of the Bauhaus is evident, such as her use of free forms. Brandt opted for the triangle, cylinder, and sphere which can be seen in her famous coffee set MT50-55a (1924), ashtrays, mythical teapot MT49, and the well-known Kandem 702 lamp.

玛丽安·布兰德的吊顶灯HMB 29/Ceiling lamp HMB 29 Marianne Brandt © Kai 'Oswald' Seidler via Flickr License Under CC BY 2.0. Image

接下来,Brandt开始在格罗皮乌斯工作室就职,在二战之后,这位设计师在德累斯顿艺术学院进行教学工作,20世纪70年代,Marianne Brandt开始接触摄影,她也成为了实验性静物创作及自画像的先驱人物。

这些女性是包豪斯的杰出代表,其他的知名设计师如Otti Berger,是一位纺织品设计师,同时也是柏林纺织工作室的创始人,以及陶艺大师Marguerite Friedlaender-Wildenhain,她的陶艺工作室Pond Hall运营得风生水起,在美国享有极高的盛誉,另外还有玩具设计师Alma Siedhoff-Buscher。

Brandt then began to work at the Walter Gropius studio. After the Second World War, the designer devoted herself to teaching at the faculty of arts in Dresden. In the 1970s, Marianne Brandt took up photography. She is remembered as a pioneer of experimental still life and self-portraits.

These women are just three great examples of the many outstanding roles women played at the Bauhaus. Other great artists include Otti Berger, a textile designer and founder of the famed Berlin shop Atelier for Textiles; the potter Marguerite Friedlaender-Wildenhain, who achieved fame in the US thanks to her pottery Pond Hall; and the toy designer Alma Siedhoff-Buscher.

玛丽安·布兰德的水壶/Chaleira 1924 Marianne Brandt © William Cromar via Flickr License Under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0. Image

在当时,女性不仅在经营好自己家庭的同时,也通过工作的方式证明自己存在的价值。只是当时的女性如果对艺术有所追求,受条件限制,只能研究一些诸如纺织等“女性化”的方向。因为在纺织艺术当中,女性能够找到自己的艺术追求,同时对社会做出相应的贡献。因此,这些女性设计师也成为了这些领域的代表人物,而此类艺术形式也深受人们的赞赏。通过各种工艺,她们能够很好地表达自己的情感,甚至将自己的家庭也打造成艺术品王国。

Gunta Stölz曾经说:“我们想要具有当代意义的生活,同时适应于全新的生活方式,每个领域都有巨大的潜能等待挖掘,但重要的是,我们要通过材质、韵律、比例、色彩以及形式来塑造属于我们自己的艺术品。”她们十分成功,但背后的故事却几乎无人所知。

They had the audacity to prove their worth during a time when women were relegated to the home and family. If a woman wanted to pursue an artistic career, she was only allowed to study “feminine” forms of art such as weaving, regardless of the many talents she had shown in painting or sculpture. It was believed that if women were allowed to weave, they could placate their artistic sensibilities and return to the path that society marked for them. However, these women became pioneers of hand-crafted design, an art form that is much more appreciated today. By mastering their craft, they were able to express themselves and therefore transform home objects and materials into modern masterpieces.

As Gunta Stölz said, "we wanted to create living things with contemporary relevance, appropriate to a new lifestyle. Before us, there was an enormous potential for experimentation. It was essential to define our imaginary world, to shape our experiences through material, rhythm, proportion, color, and form." And they succeeded, although their story is often untold.

Tapeçaria Anni Albers © jlggb via Flickr License Under CC BY 2.0. Image

出处:本文译自www.archdaily.com/,转载请注明出处。

|

-

4.jpg

(62.08 KB, 下载次数: 1489)

|