ImageCourtesy of Wikimedia user RillkeBot (Public Domain)

AD经典:哥伦比亚世界博览会

AD Classics: World's Columbian Exposition / Daniel Burnham and Frederick Law Olmsted

由专筑网李韧,邢子编译

在1851年举办的第一届水晶宫世界博览会中,美国的表现非常突出。英国媒体对此也赞不绝口,认为美国的展品更加精致与实用,“Liverpool Times”写道,“美国不会再被嘲笑,也不会再被轻视”。在欧洲,政府对于国家展馆进行了大量的投资,而美国则不同,国会对于投资这件事仍然犹豫不决,因此如果想要进行展览,相关人员只能自筹资金。由于美国的内战,政府对于国际展览的重视程度有所下降,在战争结束后,这种情况好转了很多,在1876年,美国主办了费城世界博览会。为了庆祝美国的国家精神与技术进步,本次博览会也取得了很大的成功,同时,也为美国另一场世界博览会奠定了坚实的基础,即1893年哥伦比亚世界博览会。[1]

The United States had made an admirable showing for itself at the very first World’s Fair, the Crystal Palace Exhibition, held in the United Kingdom in 1851. British newspapers were unreserved in their praise, declaring America’s displayed inventions to be more ingenious and useful than any others at the Fair; the Liverpool Times asserted “no longer to be ridiculed, much less despised.” Unlike various European governments, which spent lavishly on their national displays in the exhibitions that followed, the US Congress was hesitant to contribute funds, forcing exhibitors to rely on individuals for support. Interest in international exhibitions fell during the nation’s bloody Civil War; things recovered quickly enough in the wake of the conflict, however, that the country could host the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition in 1876. Celebrating both American patriotism and technological progress, the Centennial Exhibition was a resounding success which set the stage for another great American fair: the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893.[1]

ImageCourtesy of Wikimedia user scewing (Public Domain)

与1876年的博览会一样,1893年哥伦比亚博览会同样具有重要意义,这纪念了Christopher Columbus于1492年首次来到美国,因此,这次博览会名为“哥伦比亚世界博览会”。与费城博览会一样的是,哥伦比亚博览会也展示了美国的工业创新技术,[2]同时,本次博览会也展出了许多1876年博览会中没有的东西,即美国不仅仅在技术方面能够跟上欧洲进步的脚步,同时其文化水准也在不断地上升,这让美国在“旧世界”中站稳了脚跟[2]。

举办本次博览会的城市是芝加哥,这是一座位于美国中西部的大城市,在1871年的一场大火之后,芝加哥的发展非常迅猛。城市的人口数量与贸易交易量不断增加,因此通过这座城市来展示美国从一个乡村殖民地发展成为世界强国的历程,是再合适不过了,因为在1830年,这里还只是一座以捕猎为生的村庄,而在不到一个世纪的时间里,这里就发展成为了一座拥有各项文化设施的大都市[3]。

Like its predecessor in 1876, the 1893 Fair would have a dual significance. It was planned as a commemoration of Christopher Columbus’ first voyage to America in 1492, hence the name “World’s Columbian Exposition.” Like the Centennial Exhibition, the Columbian Exposition would also showcase American industrial capability and technological innovation.[2] However, it fell to the 1893 Fair to demonstrate something that the 1876 Fair had not: that the United States was not only the technological equal of Europe, but had risen past a century of cultural inferiority to stand on even footing with the “Old World”.[2]

The city chosen to host the Fair was Chicago, the great urban center of the Midwest which had flourished exponentially in the years since its decimation by fire in 1871. The city’s population and trade, rather than being dampened by the blaze, had actually increased by the following year. It was a fitting setting for an event which was expected to showcase America’s rise from a collection of mostly rural colonies to an international power: what had been a backwater fur-trappers’ village in 1830 had, in less than a century, developed into a full-fledged metropolis with a variety of cultural amenities.[3]

Courtesy of Wikimedia user scewing (Public Domain)

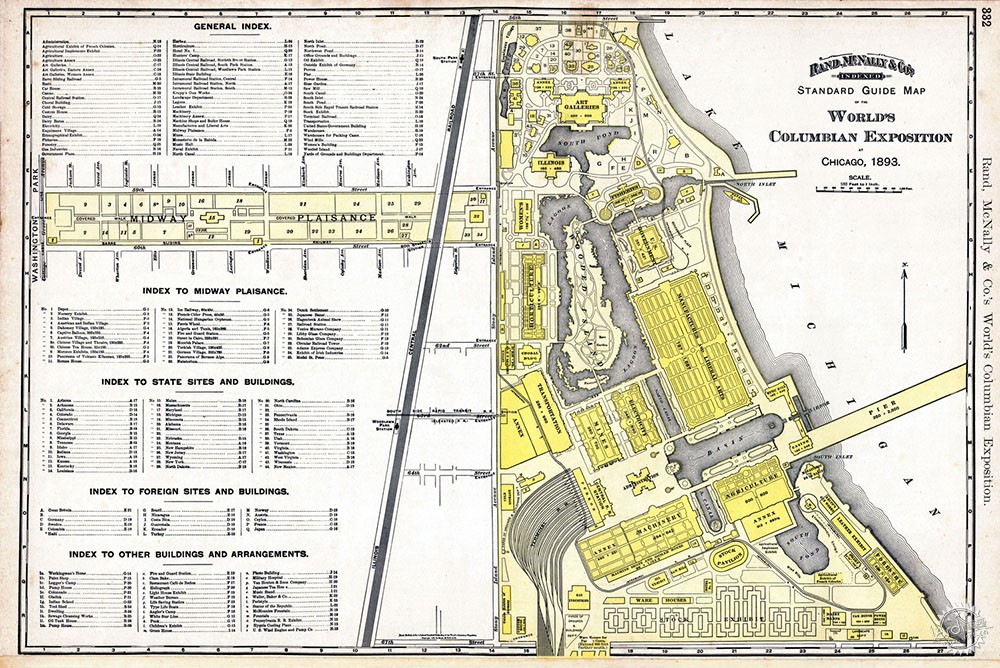

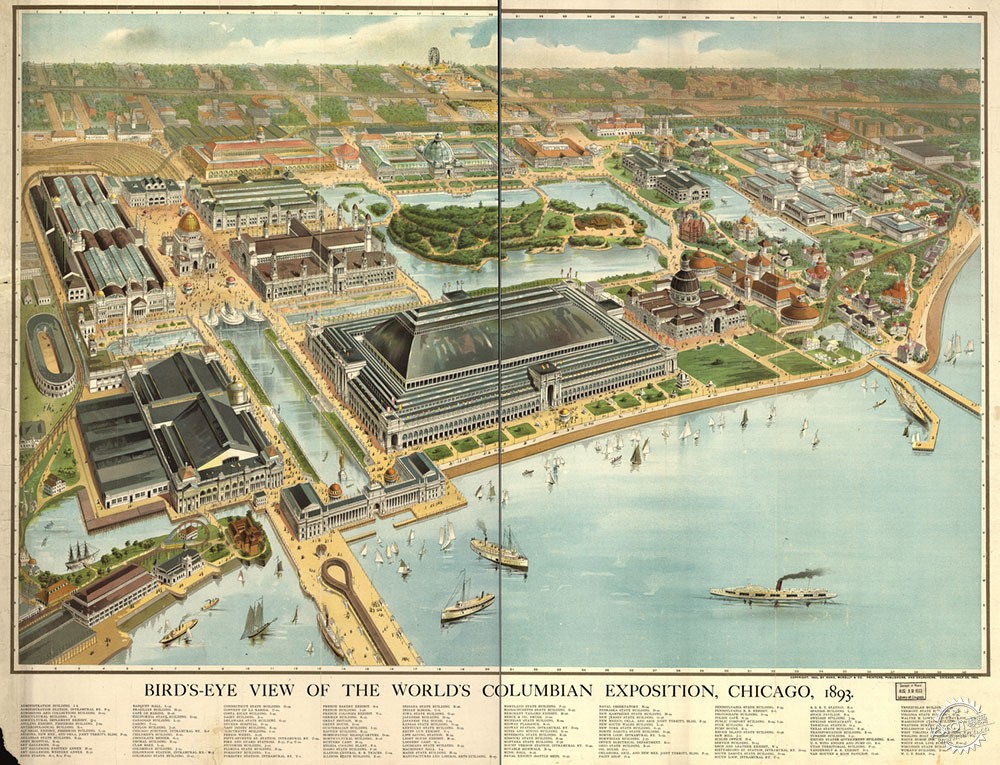

Daniel Burnham是一位著名的芝加哥建筑师,他主要负责这个项目。整个展览区的面积约为686英亩,地点位于城市南部的湖畔地区,整个项目的景观是和景观设计师Frederick Law Olmsted合作完成。建筑师团队成员分别来自芝加哥、纽约、波士顿、堪萨斯,他们共同设计博览会的建筑,建筑师的个人风格由共同的文化所统一起来,与水晶宫的金属玻璃结构不同的是,本次全新的展览展示了一座真正永恒的“梦幻城市”。 [4,5]

Daniel Burnham, a noted Chicago architect, was chosen to serve as the project’s director. At his disposal were 686 acres of land along the city’s southern lakefront, a vast swathe of land which he developed with the help of famed landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted. A team of architects from Chicago, New York, Boston, and Kansas City was gathered to produce the Fair’s individual buildings. Their individual efforts were united by a stylistic mandate: rather than the metal-and-glass pavilions that had characterized World’s Fairs since the Crystal Palace, this new exhibition would take on the appearance of a real and permanent “dream city” realized in the Beaux-Arts style.[4,5]

Courtesy of Wikimedia user Tuvalkin (Public Domain)

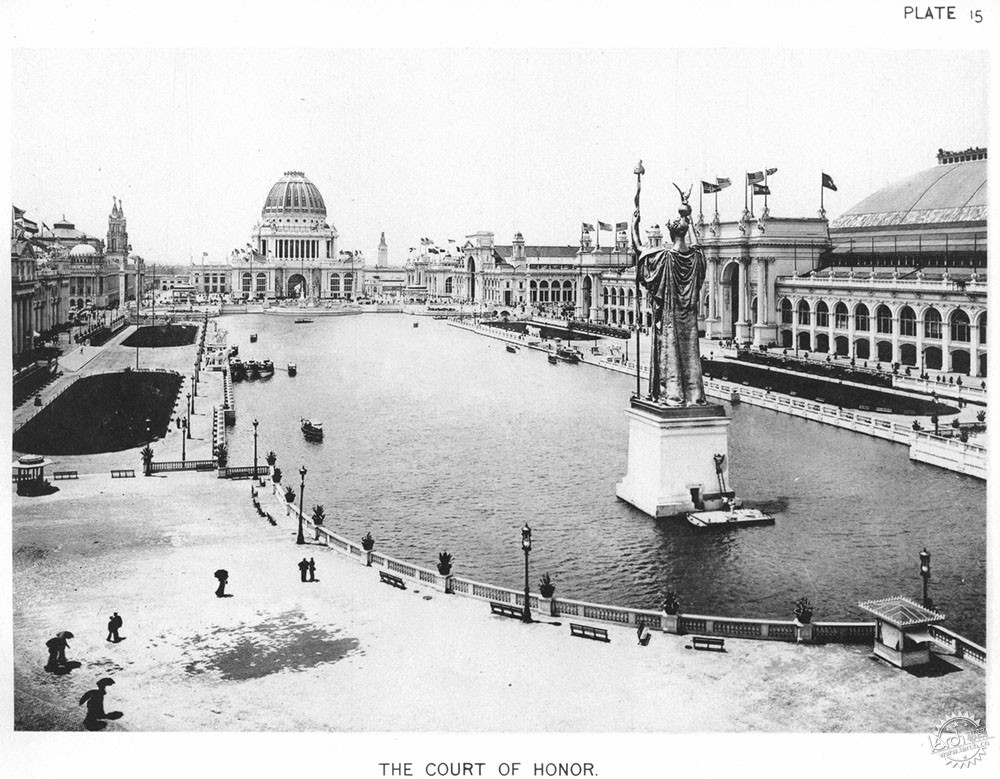

项目从规划到建造,时间大约不到两年半,Burnham团队同时也拒绝了一些想法,即设计出更加壮观的“埃菲尔铁塔”,因为这些方案在很大程度上只是再一次强调了新古典主义美学。[6]密歇根湖畔的全新城市与芝加哥城市的其他部分形成明显的对比,这是一个宏伟有序的序列,沿着法院轴线而排布,并且与密歇根湖交相辉映。整个场景在夜晚灯火通明,让城市沐浴在超凡脱俗的光芒之中,对于参与者而言,这样的光芒将他们与传统的工业城市完全隔离开。[7]

The team had less than two and a half years to plan and build their new city. A slew of proposals, many of which were for towers designed to outshine the Eiffel Tower of 1889’s Exposition, were presented and rejected by Burnham’s team, which largely enforced the Neoclassical aesthetic throughout the fairgrounds.[6] The new city that arose on the shores of Lake Michigan was a gleaming antithesis to the rest of Chicago: an orderly ensemble of grandiose, stylistically harmonious structures arranged around an axial court of honor and reflected in a series of lagoons. The entire scene was electrically floodlit at night, bathing the city in an otherworldly glow which, to attendees, would have made the fairgrounds feel entirely removed from the industrial cities to which they were accustomed.[7]

ImageCourtesy of Wikimedia user RillkeBot (Public Domain)

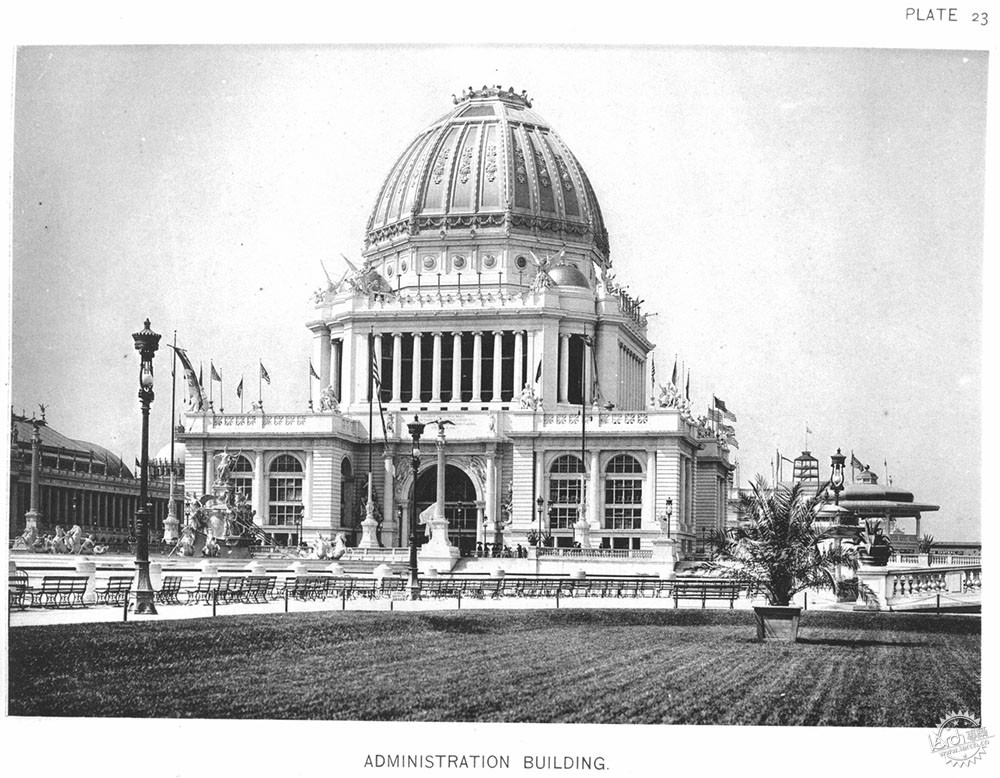

游客可以通过三个入口进入展览区,行人可以从芝加哥市区的沿街面进入博览会码头,而大多数游客则来自于场地南侧的火车站。这些游客首先会到达大型行政中心。这座巨大的穹顶建筑由纽约建筑师Richard M. Hunt设计,这里是世界博览会的行政办公场所。同时拥有14座世博会建筑的主要特征,即有着高度为60英尺(约18.25米)的统一檐口、白色粉刷墙体,以及几何Beaux-Arts美学体系[8]。

Three entrances allowed visitors into the fairgrounds. Pedestrians could enter from the street onto the Midway or take a steamboat from downtown Chicago to a pier on the Fair’s lakefront. Most visitors, however, arrived via the railroad terminus at the southern end of the grounds. Those who entered via the two latter means first encountered the monumental Administration Building. Designed by New York architect Richard M. Hunt, the enormous domed building housed the offices of the Exposition’s chief officers. It also set the tone for the Exposition’s fourteen “great” buildings, establishing a uniform cornice height of 60 feet (18.25 meters) and a white-stuccoed, geometrically logical Beaux-Arts aesthetic.[8]

ImageCourtesy of Wikimedia user RillkeBot (Public Domain)

博览会的其他几座重要建筑和荣誉法院以及行政中心的Great Basin呈线性形态而排布,其中有机械馆、制造与文艺馆、电力馆、矿业馆,除了最后两座建筑,其他的建筑都由不同的设计事务所设计。这里是理想城市的核心地带,建筑师都明白这些建筑需要有统一的风格。在这样的前提下,建筑师不仅仅都运用了统一的檐口线,同时还运用了25英尺(约7.6米)的凸窗作为建筑立面的标准化体系。[9]

Several of the Fair’s other important buildings lined the same court of honor and Great Basin as the Administration Building: the Machinery Hall, the Manufacturers and Liberal Arts Building, the Electricity Building, and the Mines and Mining Building, all of which, with the exception of the last two, were designed by separate firms. Here, at the center of the ideal city, the architects knew their respective buildings required a unity beyond the basic style template. With this in mind, they agreed not only to match their cornice lines, but to use a twenty-five foot (7.6 meter) bay as a standard module for the façades of their buildings.[9]

ImageCourtesy of Wikimedia user RillkeBot (Public Domain)

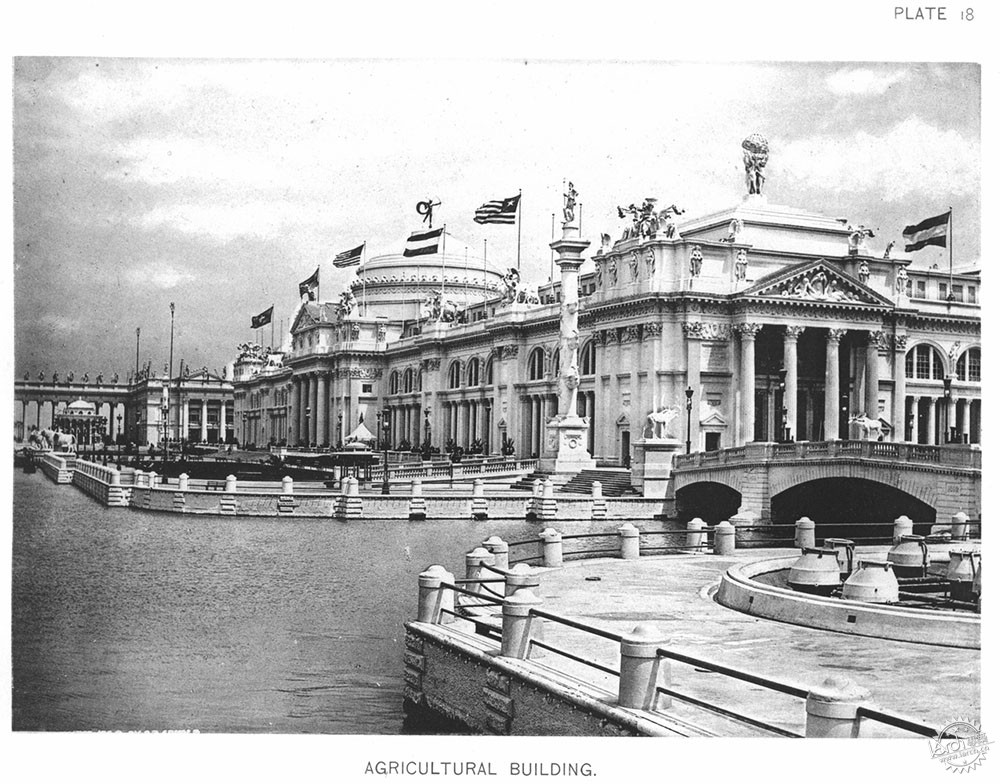

机械馆位于行政中心的南侧,如同周边的其他建筑那样,机械馆同样拥有古典的立面形态,其中包含着海绵状的展览空间,这里展示了诸多作品,这座建筑由波士顿Peabody & Stearns事务所设计,面积为435500平方英尺(约40,459.27平方米),这里展示了许多全新的技术,例如缝纫机和世界上最大的传送带。展厅中还有着43台蒸汽机和127台发电机,供应着整个博览会的电力系统。纽约McKim, Mead,, & White事务所设计了机械馆旁侧的农业馆,这里展示了来自世界各地的农业产品,其中有由腌菜制作而成的美国地图,还有来自加拿大的“奶酪妖怪”。 [10]

Just south of the Administration Building, the Machinery Hall was, like most of its neighbors, a Classical façade hiding a cavernous single exhibition space packed tightly with exhibits. Designed by the Boston firm Peabody & Stearns, the 435,500 square feet (40,459.27 square meters) of floor space in the Machinery Hall were unsurprisingly filled with technological marvels of the time, such as sewing machines and the world’s largest conveyor belt. The Hall also housed the 43 steam engines and 127 dynamos which provided electricity for the entire Fair. McKim, Mead,, & White of New York designed the neighboring Agricultural Hall, featured farm equipment and produce from around the world, including such unusual items as a map of the United States made of pickles and a 22,000 pound “Monster Cheese” from Canada.[10]

ImageCourtesy of Wikimedia user RillkeBot (Public Domain)

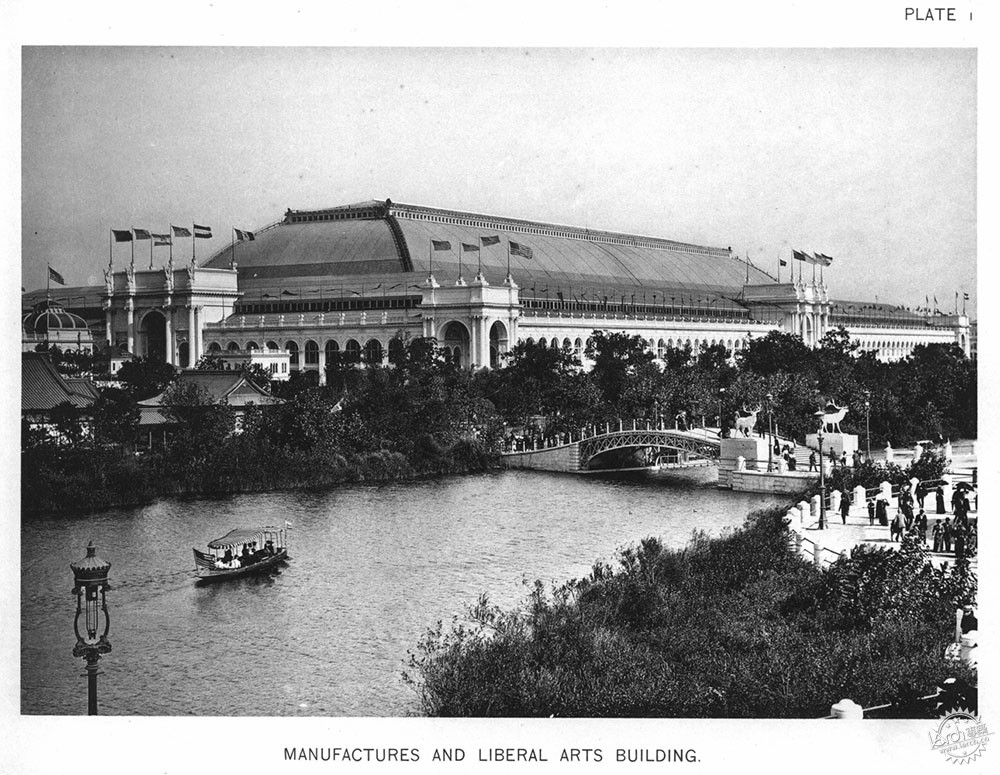

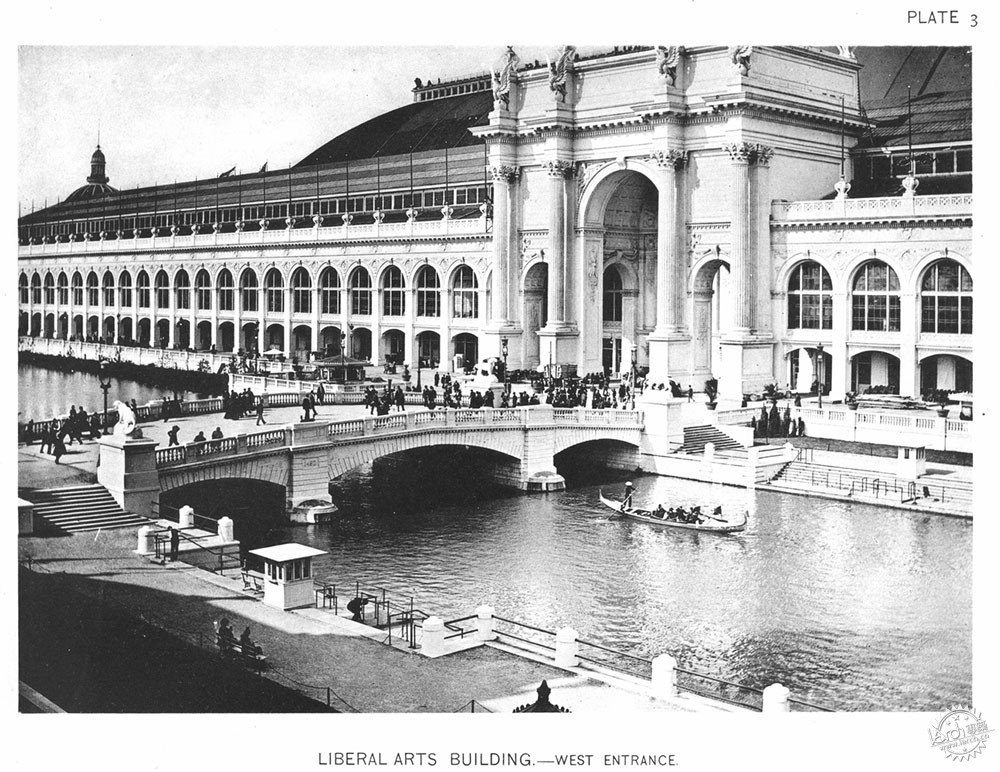

博览会上的最大建筑是制造与文艺馆。这座建筑占地11英亩,展示了来自世界各地的产品。在那些来自美洲、欧洲、亚洲的展品中,参观者可以感受各种具有历史意义的作品,其中包括来自巴伐利亚的家具和莫扎特的竖琴。[11]由于建筑的体量实在太大,这座展馆甚至沿着密歇根湖畔延伸了长达3英里(约5公里)。[12]

The largest building at the Fair, by far, was the Manufacturers and Liberal Arts Building. Covering a full eleven acres, the enormous structure was used to display consumer goods not only from the United States, but from around the world. Between exhibits by manufacturers from the Americas, Europe, and Asia, visitors could also view assorted items of historical significance, including furniture owned by the King of Bavaria and a spinet which had belonged to Mozart.[11] The Manufacturers and Liberal Arts Building was so large that its waterfront façade extended for a third of a mile (.5 kilometers) along the shore of Lake Michigan.[12]

ImageCourtesy of Wikimedia user RillkeBot (Public Domain)

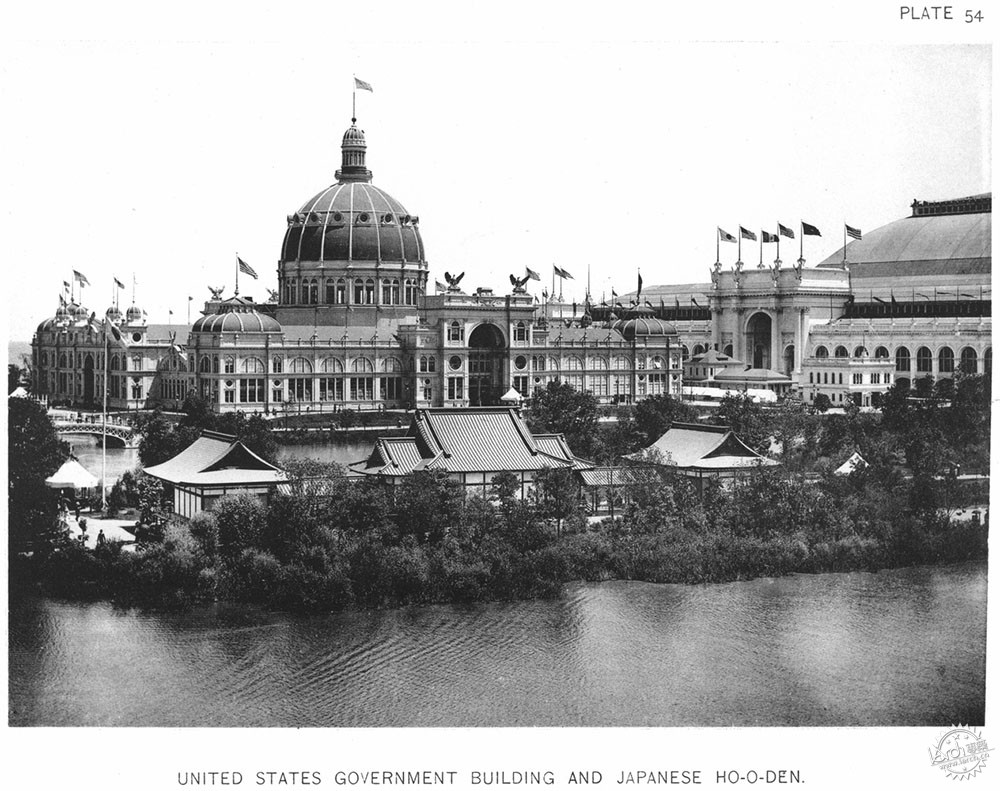

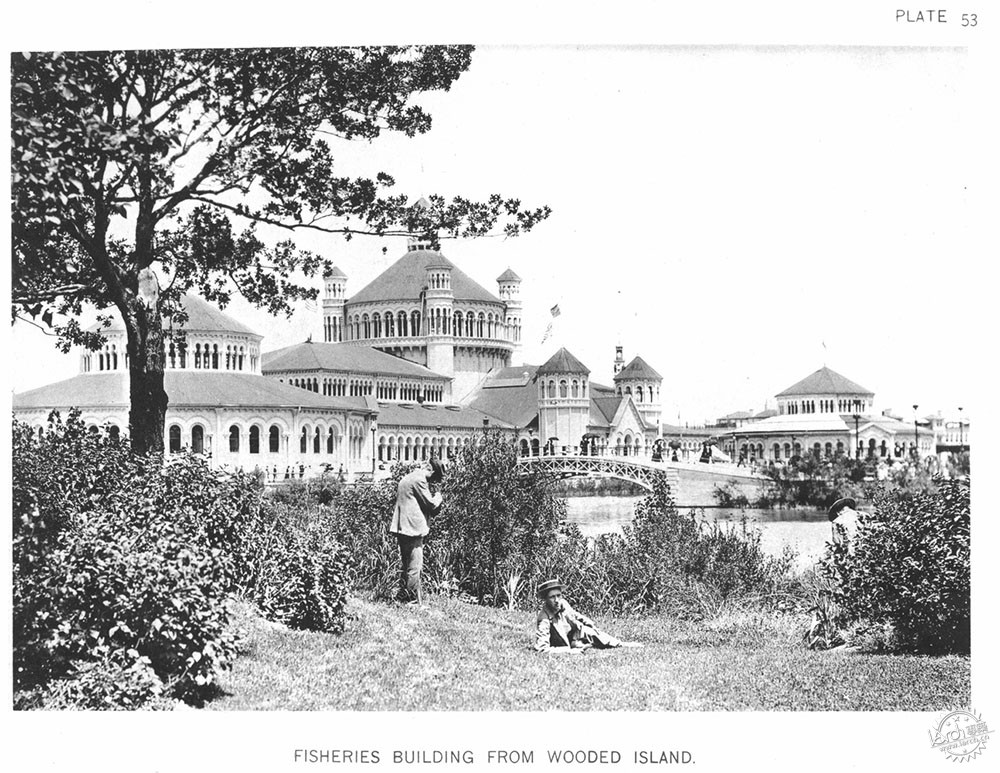

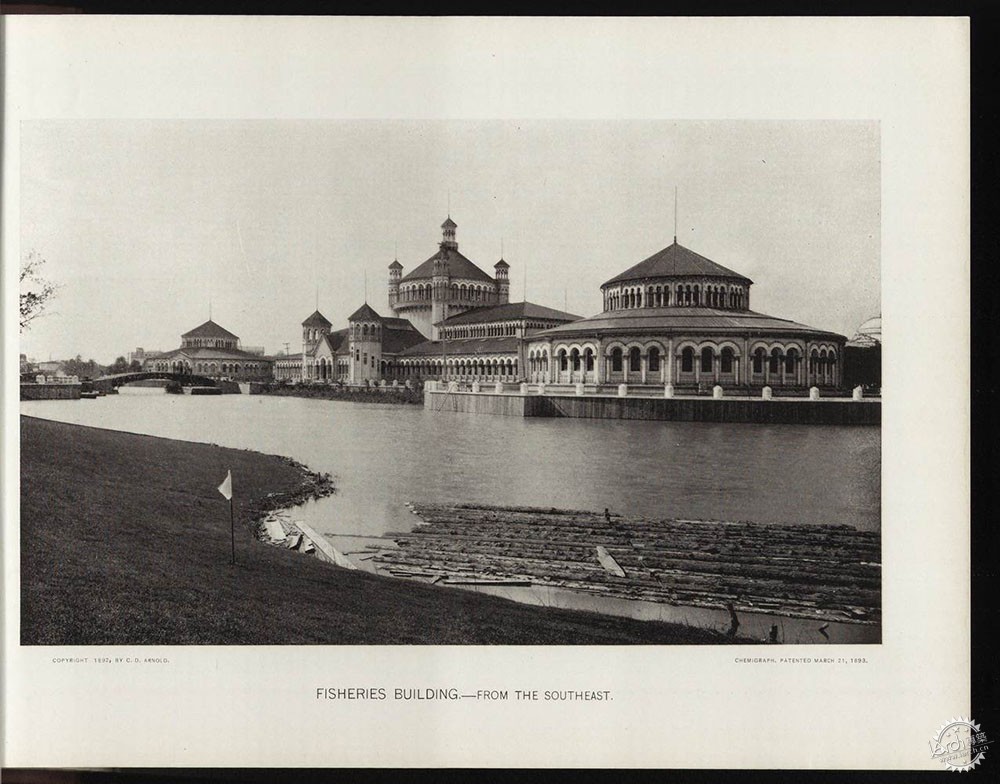

制造与文艺馆的北面是美国国会大厦和渔业馆。前者由美国财政部门的建筑师J.W. Edbrooke设计,这座建筑看上去较为低调,展示了美国政府的许多展品。相比起旁边的渔业馆而言,这座建筑相对普通。渔业馆由芝加哥建筑师Henry Ives Cobb设计,建筑打破了Great Basin其他建筑的Beaux-Arts审美标准以及荣誉法院多彩玻璃的标志。最吸引游客的是建筑通高的玻璃水族馆,其中展示了成百上千种咸水鱼和淡水鱼。

To the north of the Manufacturers and Liberal Arts Building stood the U.S. Government Building and the Fisheries Pavilion. The former, designed by the Treasury Department’s supervising architect J.W. Edbrooke, was a relatively modest structure containing displays from various branches of American government. It was not considered among the Fair’s better offerings, especially when compared to the Fisheries Pavilion just across the lagoon. Designed by Chicago’s own Henry Ives Cobb, the Pavilion broke from the whitewashed Beaux-Arts standard of the buildings on the Great Basin and court of honor with colorful glazing and flags. The highlight for visitors, however, were the floor-to-ceiling aquaria within the building, which contained hundreds of species of fresh and saltwater marine life.[13,14]

ImageCourtesy of Wikimedia user RillkeBot (Public Domain)

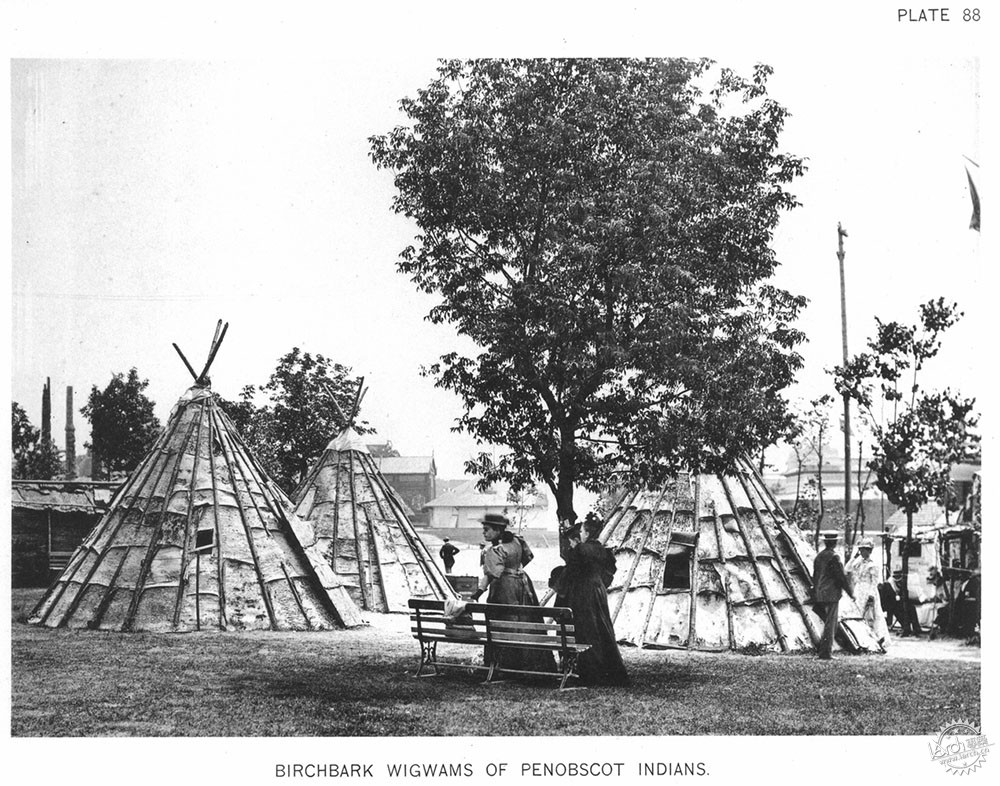

43个美国州和23个国家都在本次展览会上展示了自己的建筑,与一些大型建筑不同的是,很少有建筑是通过Beaux-Arts风格来表达形态。项目的资金委员会也同样负责建筑的设计工作,于是便有了风格各异的折中式建筑,其中既有加利福尼亚展馆的西班牙殖民式风格,也有佛蒙特州展馆的庞贝风格。在Wooded岛上甚至还有中世纪的日式建筑,位于Olmsted的泻湖中央。[15]

Altogether, forty-three US states and twenty-three other countries contributed their own buildings to the Exposition. Unlike the larger main buildings, these were less likely to be rendered in Beaux-Arts style. The committees in charge of funding these pavilions were also tasked with designing them, resulting in an eclectic collection of styles ranging from Spanish Colonial in the California Pavilion to a reproduction of Pompeii by Vermont. There were even medieval Japanese structures on the Wooded Island that rose from the middle of Olmsted’s relatively naturalistic lagoon.[15]

ImageCourtesy of Wikimedia user RillkeBot (Public Domain)

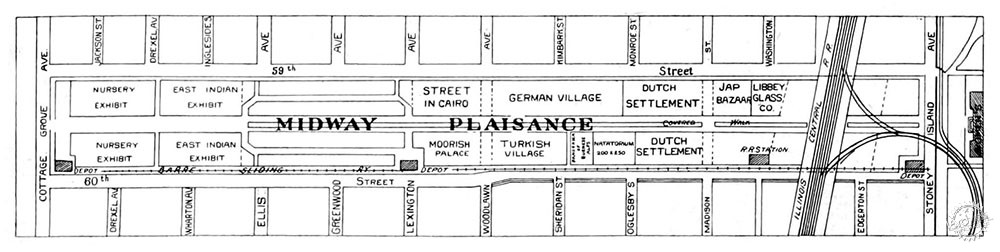

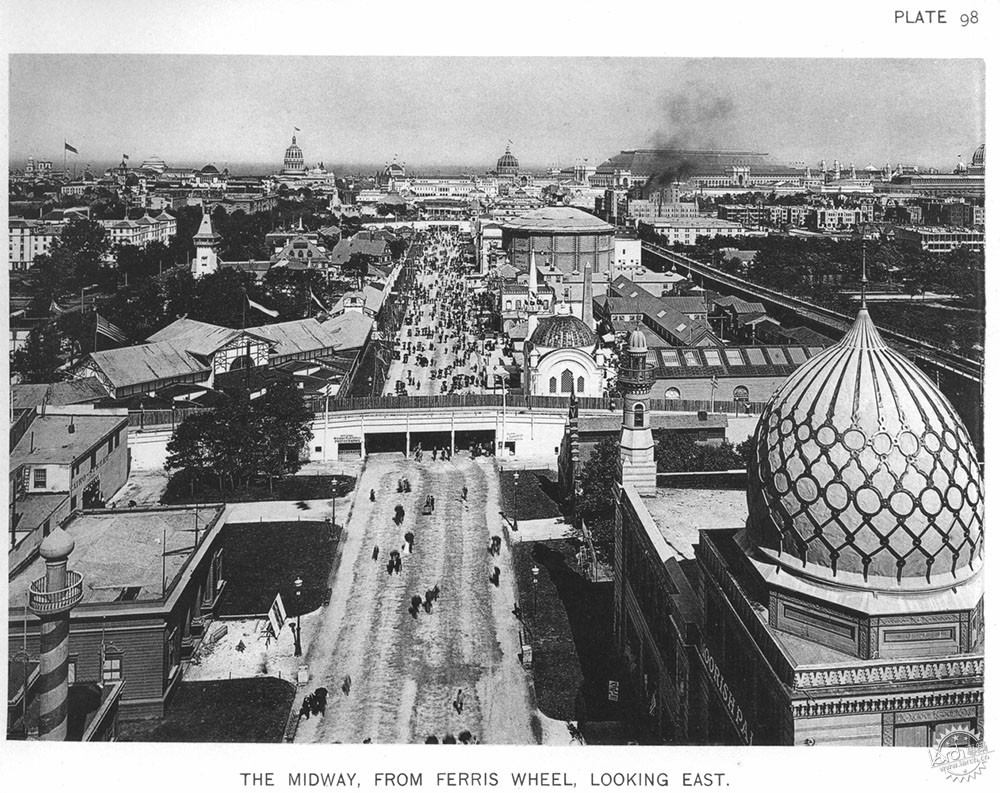

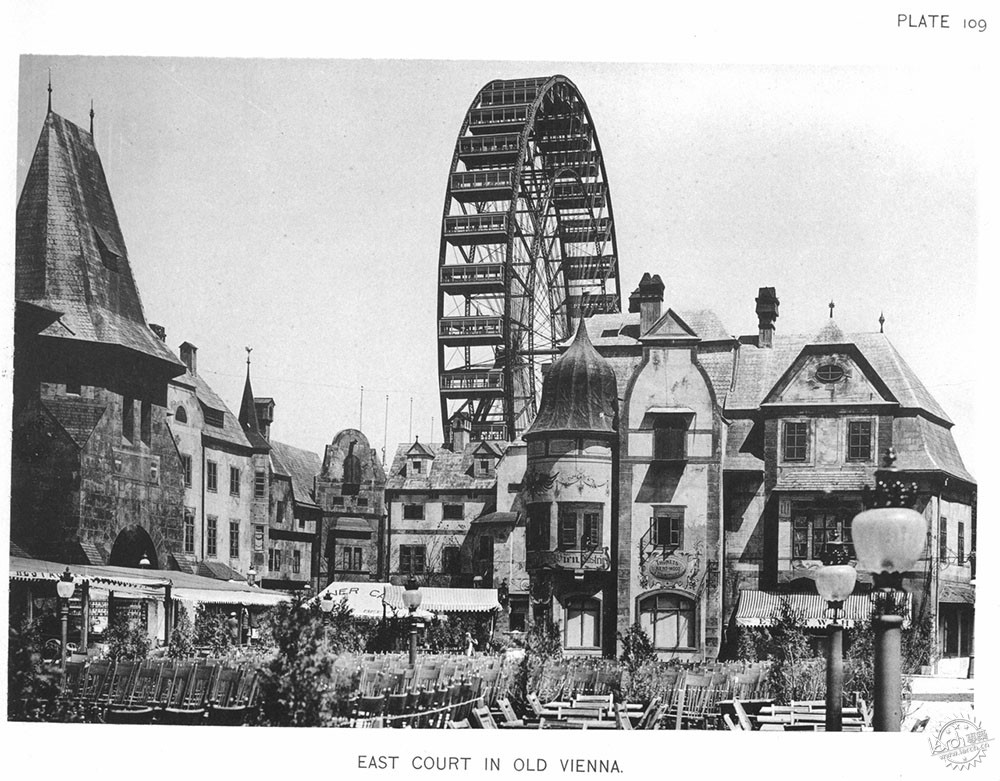

然而博览会中最让人难忘的元素却与核心建筑无关,即Midway Plaisance。虽然这座建筑最初的设计目的是教育功能,但在后来却成为了博览会的娱乐中心。游客可以参观到开罗与维也纳的街头作品,亦或是德国或爪哇村落的产品,以及摩尔宫殿的蜡像。也许Midway最为著名的便是世界上第一座摩天轮,但是乘坐费用却是博览会门票的两倍。[16]

One of the most memorable elements of the Exposition had little to do with monumental architecture: the Midway Plaisance. Although initially intended to be educational, the Midway ultimately became the entertainment center for the fair. Visitors could visit reproductions of streets in Cairo or Vienna, see both a German and a Javanese village, or enjoy the wax figure museum in the Moorish Palace. Perhaps the most famous of the Midway’s amenities was the world’s first Ferris Wheel, a ride on which cost twice as much as admission to the entire fair.[16]

ImageCourtesy of Wikimedia user RillkeBot (Public Domain)

哥伦比亚世界博览会的影响非常深远。项目场地被人们称呼为“白色城市”,也为后来的城市美学运动奠定了基础。Olmsted的公园和水域的设置背景灵感来源于博览会主要建筑的新古典主义美学,诸如Burnham这样的建筑师将原本“肮脏丑陋”的工业城市改造成为一座全新的白色城市。这次运动不仅仅促进了芝加哥的城市发展,同时也促进了美国的整体发展,从西部的旧金山到东部的华盛顿,都在这场博览会中获益诸多。这次博览会传递了一种设计哲学,捕捉了建筑师与城市规划者的创新意识,也是众多博览会中最为成功的一大案例。[17]

The effects of the World’s Columbian Exposition were both immediate and far-reaching. The fair grounds, affectionately nicknamed “The White City,” laid the groundwork for what soon became known as the City Beautiful movement. Inspired by the Neoclassical harmony of the Exposition’s main buildings, set against the backdrop of Olmsted’s manicured parks and waterways, architects like Burnham would soon set out to transform what they saw as dirty, unsightly industrial cities into elegant and orderly successors to the White City. The movement gained traction not only in Chicago, but across the entire United States, from San Francisco in the west to Washington, D.C. in the east. It was a design philosophy which captured the imagination of a generation of architects and urban planners – one which long outlasted the temporary structures of the Exposition that proved its first—and most successful—example.[17]

Courtesy of Wikimedia user RillkeBot (Public Domain)

Courtesy of Wikimedia user RillkeBot (Public Domain)

Courtesy of Wikimedia user scewing (Public Domain

Courtesy of Wikimedia user RillkeBot (Public Domain)

参考文献

[1] Muccigrosso, Robert. 庆祝新世界:1893年芝加哥世界博览会.芝加哥: I.R. Dee, 1993. p5-13.

[2] Kostof, Spiro. 建筑历史:装置与仪式:国际第二版. 纽约:牛津大学出版社, 2010. p669.

[3] Burg, David F. 1893年芝加哥白色城市. Lexington, KY: 肯塔基大学出版社, 1976. p45-48.

[4] Kostof, p669.

[5] "哥伦比亚世界博览会." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2017年5月24日. [访问].

[6] Burg, p75-80.

[7] Kostof, p670.

[8] Rose, Julie K. "博览会之旅 – 第一部分." 哥伦比亚世界博览会:官方博览会——虚拟旅程. 1996.2017年5月24日访问. [访问].

[9] "1893年哥伦比亚世界博览会." 1893年哥伦比亚世界博览会. 1999年2月26日. [访问].

[10] Rose, “博览会之旅 – 第一部分.”

[11] Rose, “博览会之旅 – 第一部分.”

[12] “1893年哥伦比亚世界博览会.”

[13] Rose, “博览会之旅 – 第一部分.”

[14] “1893年哥伦比亚世界博览会.”

[15] Rose, Julie K. "博览会之旅 – 第二部分." 哥伦比亚世界博览会:官方博览会——虚拟旅程. 1996.2017年5月24日访问.[访问].

[16] Rose, “博览会之旅 – 第二部分.”

[17] Blumberg, Naomi, Ida Yalzadeh. "城市美学运动." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2014年,6月24日. [访问].

References

[1] Muccigrosso, Robert. Celebrating the New World: Chicago’s Columbian Exposition of 1893. Chicago: I.R. Dee, 1993. p5-13.

[2] Kostof, Spiro. A history of architecture: settings and rituals: international second edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010. p669.

[3] Burg, David F. Chicago’s White City of 1893. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 1976. p45-48.

[4] Kostof, p669.

[5] "World's Columbian Exposition." Encyclopædia Britannica. May 24, 2017. [access].

[6] Burg, p75-80.

[7] Kostof, p670.

[8] Rose, Julie K. "Tour the Fair - Part 1." World's Columbian Exposition: The Official Fair--A Virtual Tour. 1996. Accessed May 24, 2017. [access].

[9] "World's Columbian Exposition of 1893." World's Columbian Exposition of 1893. February 26, 1999. [access].

[10] Rose, “Tour the Fair - Part 1.”

[11] Rose, “Tour the Fair - Part 1.”

[12] “World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893.”

[13] Rose, “Tour the Fair - Part 1.”

[14] “World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893.”

[15] Rose, Julie K. "Tour the Fair - Part 2." World's Columbian Exposition: The Official Fair--A Virtual Tour. 1996. Accessed May 24, 2017. [access].

[16] Rose, “Tour the Fair - Part 2.”

[17] Blumberg, Naomi, and Ida Yalzadeh. "City Beautiful movement." Encyclopædia Britannica. June 24, 2014. [access].

建筑设计:Daniel Burnham、Frederick Law Olmsted

地点:美国 芝加哥

主创建筑师:Daniel Burnham

景观设计:Frederick Law Olmsted

项目时间:1893年

Architects:Daniel Burnham and Frederick Law Olmsted

Location:Jackson Park, 1793 E Hayes Dr, Chicago, IL 60649, United States

Architect in Charge:Daniel Burnham

Landscape Designer:Frederick Law Olmsted

Project Year:1893

|

|