Image © Naman Saraiya

我们需要DIY建筑活动来应对气候变化

We Need DIY Activist Architecture to Fight Climate Change

由专筑网小R,王雪纯编译

建筑与政策、政治、权力之间都存在着内在联系,建筑师所肩负设计的责任与其对建筑环境的感知,对于塑造城市人居环境起到了重要的作用。世界面临着许多挑战,例如气候变化、移民问题、经济适用房缺乏等等,建筑师愈发地出现在了变革的前线,通过各种策略与方式来促进变革。尽管有很多官方渠道供建筑师们倡导环境变革,但是下文将提出一种既不那么官僚主义,又注重实践活动的让城市环境发展“少走弯路”的改革方法。

建筑师对于空间的感知十分敏锐,有时建筑不过是他们所创造的一种艺术材料。对于建筑师而言,他们也愈发地感受到,这个世界上的许多问题都缺乏政治策略,他们希望用自己的力量来推进策略的变革,城市艺术活动有能力激发人们的共识。

如果要做到这一点,那么建筑师就必须真正地发挥作用,成为城市的活动家。

Architecture is inherently linked to policy, politics, and power. With responsibility for the design and perception of the built environment, architects have a distinct role in shaping the human urban experience. As the world confronts issues of climate change, forced migration, and affordable housing, architects are increasingly putting themselves on the front line of the debate, using a variety of tools and avenues to clamor for change, and indeed design for it. However, while many official avenues exist for architects to advocate for social and environmental reform, there is an under-theorized method of resistance, a ‘road less traveled’ for social progress beyond officialdom.

With crafted skills centered on the human perception of space, architects can engage in a movement seeking to use architecture as a raw material for unsanctioned artistic intervention. For architects increasingly alarmed at a perceived lack of political action to the world’s pressing issues, and eager to use their skills to promote change, artistic urban activism has the power to spark awareness, dialogue, and reform.

To do this, architects must become more than a cog in a formal planning machine. Architects must become unsanctioned urban activists.

© Shutterstock

艺术与行动主义

无论是抽象还是实体,艺术都能够激发人们的各种反应,给人们带来新视角与新思维,艺术可以是政治与社会活动的推动因素和媒介(Groys, 2014, p.1),几十年以来,艺术常常以批判的视角出现,但是近期的全球艺术“行动主义”已经超出了批判的范畴。“艺术活动家希望能够改变经济不发达地区的生活条件,并且提出了生态问题,关注非法移民事件,改善艺术机构的工作环境等等”(Groys, 2014, p.1)。这些多种艺术活动能够通过诸如音乐、文学、戏剧、视觉、空间等方式得以表达。

艺术能够打破人们情感障碍的能力,这就是艺术作为行动主义的能量。这种力量的起源可以追溯到儿童的教育,在那个时候,几乎所有人都对艺术有所了解,例如舞蹈、绘画、音乐、摄影、诗歌、陶器等等,而人们在幼童阶段也经历了许多艺术活动,例如铅笔画、拼贴画等等。除了诸如数学、科学、语言等基于认知程度且有明确对错之分的学科,“艺术能够利用人们的直觉来表达自己的情感,并且构成相对客观的框架体系”(Shank, 2004, p.535)。对于年轻人而言,艺术更有尊重性和直观性。在以理性认知为主导的成年人生活中,激进主义艺术家发现了另一种思维方式。

这种认知与情感的结合需要“在巨大情感能力、符号灵活性、文化敏感性的过程中进行世界观的转变,而这个过程来源于传统的行动主义,同时受到战略性艺术行动主义的刺激”(Shank, 2004, p.555)。艺术行为主义是改革的催化剂,并且也成功地赢得了一种强大但却未被充分利用的工具,那便是人心。对于建筑师而言,艺术行动主义就是空间行动主义,这是对于公共空间的使用,也是对建筑环境的改造,能够激发人们的情感共鸣,同时激活城市的发展,激发创造力,甚至改变人们的思维模式。

文化绑架

在艺术的世界里有许多空间行动主义的操作方式,但是目前而言,针对城市行动主义的理论仍然较少,其中一个概念名为“文化绑架(Cultural Hijack)”,这个概念由活动家、艺术家,以及学者Ben Parry博士于2011年提出。“文化绑架”可以看做是一种方法或者是运动,但是无论是何种标签,它的关注点都是空间干预的作用,空间干预是社会规范的挑战之一。“文化绑架”会针对特定的场所,寻求与公众的沟通,通过利用不同的力量来拓宽人们的思想和意识,打开新的想法,寻求新的契机,同时也是对于如今热门话题的回应。

“文化绑架”常常超越公共艺术的范畴,由“少部分将自己的艺术作品与激进社会或是政治变革联系在一起的艺术家或艺术团体”(Sholette, 2017, p.160)所操纵。这种干预措施其实并不受欢迎,因为它并不是一种利用艺术来促进社会与政治交流的明确运动。“这种非官方做法一般发生在城市的边缘地区,因为这里会有一些监管上的漏洞”(Parry, 2011, p.31)。

而在“文化绑架”中,建筑则成为了核心角色,因为这一行为有着强烈的场地特殊性。建筑是这种行为的主要内容,“文化绑架从抽象的空间逐步向城市的真实空间去发展”(Parry, 2011, p.28)。观察者基于真实世界的体验,能够在现实空间中表现自己。在“文化绑架”的行为中,城市成为了一块空白的画布,时刻准备着被操纵与抗争。

城市画布

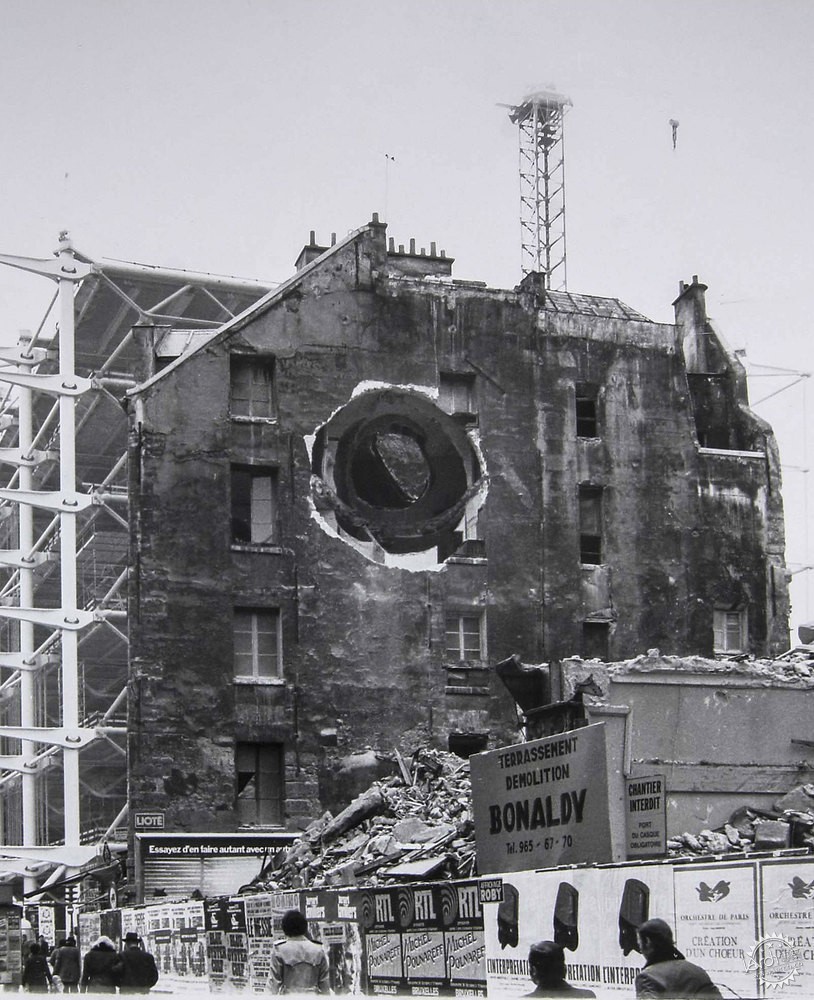

几乎所有的“文化绑架”的行为都以城市为共同背景,但是它们针对建筑的使用方式却各不相同。在“文化绑架”行为可以将诸如街道、公共广场、现代主义办公室、古典主义市政厅、废墟、烂尾楼等场所视作可随意发挥的城市画布。比如两位知名的城市活动家Gordon Matta-Clark就Jochen Gerz的风格就各有千秋,他们表达了“文化绑架”在城市中的多种表达形式,以及建筑设计者在城市中的行为的各种可能。

美国艺术家Gordon Matta-Clark的作品“定义了那些未经批准的DIY策略,正好表达了‘文化绑架’的核心内容”(Parry, 2011, p.14)。Matta-Clark改造了纽约一处城市边角空间,将一个垃圾处理单元改造为城市剧院,并且通过剩余的材料建造了收容所。通过这些实时的干预措施,Matta-Clark希望能够创造出触发人们心弦的艺术作品,而这些作品能够超出人们的一般审美标准。Matta-Clark的作品和大部分城市行动主义作品类似,既也批判的一面,也有革新的一面。

Art and Activism

Whether abstract or spatial, the arts have a unique ability to evoke a reaction within the observer or participant, unlocking new points of view, and new frames of mind. This capacity lies central to “the ability of art to function as an arena and medium for political protest and social activism” (Groys, 2014, p.1). Whilst the role of art as ‘criticism’ has existed for decades, a recent global phenomenon of art ‘activism’ has reached beyond critique. “Art activists try to change living conditions in economically underdeveloped areas, raise ecological concerns…attract attention to the plight of illegal immigrants, improve the conditions of people working in art institutions, and so forth” (Groys, 2014, p.1). There are several media through which this artistic activism can manifest, including musical, literary, dramatic, visual, or spatial.

The power of art as activism lies in the unique ability of art to break the emotional barriers of the observer. The origin of this power can be traced back to childhood education, where almost all pupils would have experienced the arts, enlisted in dance, painting, music, photography, poetry, pottery, and at a pre-school level, more improvisational activities such as pencil, crayon, and collage drawings. Set aside from cognitive-based, ‘right or wrong’ subjects such as mathematics, science, or language, “art capitalizes on the intuitive self ability to spontaneously express itself and provides a less judgemental framework” (Shank, 2004, p.535). To the young, art is an experience where judgment is replaced with respect, and prejudice with intuition. Activist art rediscovers and reignites this alternative channel of thought within the observer in an adult life dominated by cognitive constructs.

This marriage of cognitive and emotional argument permits “the transformation of entrenched world-views [in] a process that requires immense emotional intelligence, symbolic dexterity, and cultural sensitivity…procured by means of traditional fact-based activism and spurred by strategic art activism” (Shank, 2004, p.555). As a catalyst of transformation, art activism succeeds in winning both ‘hearts and minds’, a powerful yet underutilized tool the arsenal of social justice. For architects, artistic activism is spatial activism. It is the occupation of public space, and the alteration of the built environment to awake the user’s emotional and cognitive capacities. It is activation of the urban realm as a stage of creativity, a place of protest, and a vehicle for changing hearts and minds.

Cultural Hijack

Within the realms of the art world, there exist many avenues for spatial activism to operate. However, at present, there are few definitions or supportive theories behind the enactment of urban activism. One exception is a concept known as ‘Cultural Hijack’, coined by the activist, artist and academic Dr. Ben Parry in 2011. Cultural Hijack can be interpreted as a moment, a method, or a movement. Regardless of label, it centers on the use of spatial intervention as a challenge to social norms. Always site-specific, Cultural Hijack seeks to connect with the public in real-time. By exploiting the power of the different, the curious, or the absurd, Cultural Hijack seeks to momentarily broaden the human mind, to open our consciousness to new ideas, new challenges, and new perspectives on the heated topics of the day.

Cultural Hijack frequently operates beyond the realms of commissioned public art, with operators consisting of “a small number of artists and artist groups…who explicitly link their artistic practices to radical social or political transformation” (Sholette, 2017, p.160). The intervention is often unsanctioned, with the interventionist working in the shadows, or part of an underground movement using artistic means to advance social and political dialogues. “The unofficial practice of the interventionist often takes place on the margins of the official city where it can exploit gaps in formal regulation and control” (Parry, 2011, p.31).

Architecture plays a central role in Cultural Hijack, an act heavily dependent on site-specificity. Using architecture as its raw material, “cultural hijack moves from abstract space (the world of images and signs) towards the real space of the city” (Parry, 2011, p.28). By manifesting itself in real-time, and real space, the observer becomes a participant, rooted in a real-world experience. In the act of Cultural Hijack, the city becomes a blank canvas, ready for manipulation, appropriation, and protest.

Urban Canvas

Whilst all acts of Cultural Hijack share the city as a common stage, the ways in which architecture is appropriated by Cultural Hijack can vary considerably. Side street or public square, modernist office or classical city hall, rotting ruin or stalled construction, Cultural Hijack views the entire urban realm as a canvas for appropriation. A comparison between two noted urban activists, Gordon Matta-Clark, and Jochen Gerz, exemplifies the diverse manifestations of Cultural Hijack in the urban realm, and hence the boundless possibilities of architectural designers to engage in acts of urban activism.

The activist works of American artist Gordon Matta-Clark “defined the do-it-yourself, unsanctioned interventions that embody the spirit [of Cultural Hijack]” (Parry, 2011, p.14). Matta-Clark occupied disregarded spaces of New York City, including a rubbish disposal unit transformed into a street theatre (Open House, 1972) and a homeless shelter composed of waste materials (Garbage Wall, 1970). Through impromptu interventions in real time, Matta-Clark sought to “create artworks that triggered reactions in the viewer beyond the normal, somewhat restricted aesthetic frisson available to the gallery-goer” (Atlee, 2007). As with most acts of urban activism, Matta-Clark’s work was part-critique and part-reformist.

与Matta-Clark对于城市剩余空间利用形成对比的是,“文化绑架”也可以成为公共空间的最佳位置。德国艺术家Jochen Gerz曾经发表了一篇标题为《反对种族主义纪念碑》(1993)的文章中提出了有说服力的例子。Gerz和学生历经3年时间从德国城市Saarbrucken中央广场上搬走了2000多块鹅卵石。原本的鹅卵石铺装上刻着在二战期间被亵渎的犹太墓地的名字。这些鹅卵石经过重新的铺设,名字朝下,反而铸就了反对战时对犹太社区的暴行的纪念碑。这些非官方措施与曾经的城堡广场在后来才被人们所发现,这座广场后来更名为“无形纪念碑广场”。

Matta-Clarkhe 和Gerz的措施在规模、选址、表达方式上都有着明显的对比。在Matta-Clark认为应该忽视的空间里,Gerz将其应用做城市区域的主要公共场所;在Matta Clark的作品中具有颠覆性的部分,Gerz则设计得微妙且无形;而在Matta Clark重视的某个区域,Gerz将其表现为一个被遗忘的过去。他们之间存在着许多差异,但是仍然有着同样的基本原则,那便是应用现有的建筑环境来表达艺术。

结论:文化是武器

在这样一个感性的社会里,各种运动都需要围绕着情感与认知来进行。因此艺术行动主义的出现则表达了一种强大但却未被充分利用的社会公正的工具。同时它也创造了新一代艺术家,“每位艺术家们都能够通过艺术来对抗强权”(Thompson, 2017, p.7)。艺术行动主义是改革的催化剂,以一种情感方式在人们之间建起了一座桥梁,这种情感的表达,并不是理性认知就能感受到的。

“文化绑架”并不是建筑师或是城市规划者参与艺术活动的唯一方式,但是在实际中,“文化绑架”体现了“设计的影响”的建筑宣言。城市逐步因为艺术策略而成为了一块画布,“文化绑架”给城市的人们带来了反思与批判的契机,人们可以自发地聚集起来,这表明城市活动能够触发社会的革新,而建筑师而在此起到了重要的作用。

In contrast to Matta-Clark’s use of leftover, sub-prime urban space, Cultural Hijack can also occupy prime public spaces, at the heart of urban environments. German artist Jochen Gerz offers a powerful example of artistic intervention in core public space with his intervention titled Monument Against Racism (1993). Working in the dead of night over a period of three years, Gerz and his students removed over two thousand cobblestones from the main square of the provincial capital city Saarbrucken, Germany. Once removed, the underside of each cobblestone was etched with the name of a desecrated Jewish cemetery destroyed during the Second World War. The cobblestones were then re-laid, name faced down, creating an invisible monument to wartime atrocities committed against the Jewish community. The unsanctioned intervention was subsequently discovered, and retrospectively commissioned, with the former Castle Square officially renamed the Square of the Invisible Monument.

There is a heavy contrast between the interventions of Matta-Clark and Gerz, with regards to scale, place, exposure, and manifestation. Where Matta-Clark lays claim to spaces of neglect, Gerz occupies prime public space at the symbolic center of the political urban realm. Where the work of Matta Clark is unapologetically disruptive, the work of Gerz is subtle and invisible. Where Matta Clark responded to an ignored present, Gerz responded to a forgotten past. Despite their differences, each shares a common underlying principle of site-specificity, of using the existing built environment as a raw material for artistic expression.

Conclusion: Culture as Weapon

In a society where heart and mind are entwined, any movement for change must likewise entwine the emotive and cognitive. The advent of artistic activism has therefore unveiled a powerful, underutilized tool of social justice. It has also created a new generation of artists, “the resistors: artists who use their art to resist the forces of the powerful…everyone from antiwar poster artists to artist-activists (Thompson, 2017, p.7). A catalyst of transformation, art activism bridges a void, connecting with the observer or participant on in an emotional capacity that cognitive argument struggles to convey.

Cultural Hijack is not the only avenue through which architects and urban designers can engage in artistic activism. However, in practice, Cultural Hijack has embodied the architectural mantra of ‘design for impact’. With the city being transformed into a blank canvas for activist appropriation, Cultural Hijack offers the urban public an opportunity for reflection and critical engagement, congregating in an unorganized, yet powerful solidarity; a demonstration that urban activism can be a vehicle of change, and that architects can be its agents.

参考文献

Attlee, James (2007) ‘Towards Anarchitecture: Gordon Matta-Clark and Le Corbusier’, Tate Papers, 7(), pp. [Online]. Available at: http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/07/towards-anarchitecture-gordon-matta-clark-and-le-corbusier (Accessed: 10th September 2019).

Groys, Boris (2014) ‘On Art Activism’, E-Flux Journal, 56(June), pp. 1-14.

Parry, Ben (2011) Cultural Hijack: Rethinking Intervention, Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

Shank, Michael. (2005) ‘Redefining the Movement: Art Activism’, Seattle Journal for Social Justice, 3(2), pp. 531-560.

Thompson, Nato. (2017) Culture as Weapon, New York: Melville House Publishing

|

|