“有时一座建筑并不够”

"Sometimes a Building is Not Enough": Lola Sheppard on Architecture as a Cultural Act

由专筑网小R编译

建筑的本质来源于文化和环境背景,从气候危机、远郊城市主义问题,再到乡村与偏远社区的建筑角色,这些都影响了我们的设计方式。Lateral工作室的建筑师Lola Sheppard十分关注这些动态的发展,创造了直接反应新时代需求的作品,建筑师通过批判的厕所,探索了全新的类型,而这些类型都是当前所直接面对的问题。

Architecture is inherently defined by its cultural and environmental context. From the climate crisis and questions of exurbanism to architecture’s role in rural and remote communities, broader conditions shape how we design. Embracing these dynamics, architect Lola Sheppard of Lateral Office has created a body of work that directly responds to the demands of the 21st century. Through critical and deft interventions, she is exploring new typologies made possible by an architecture that brazenly confronts today.

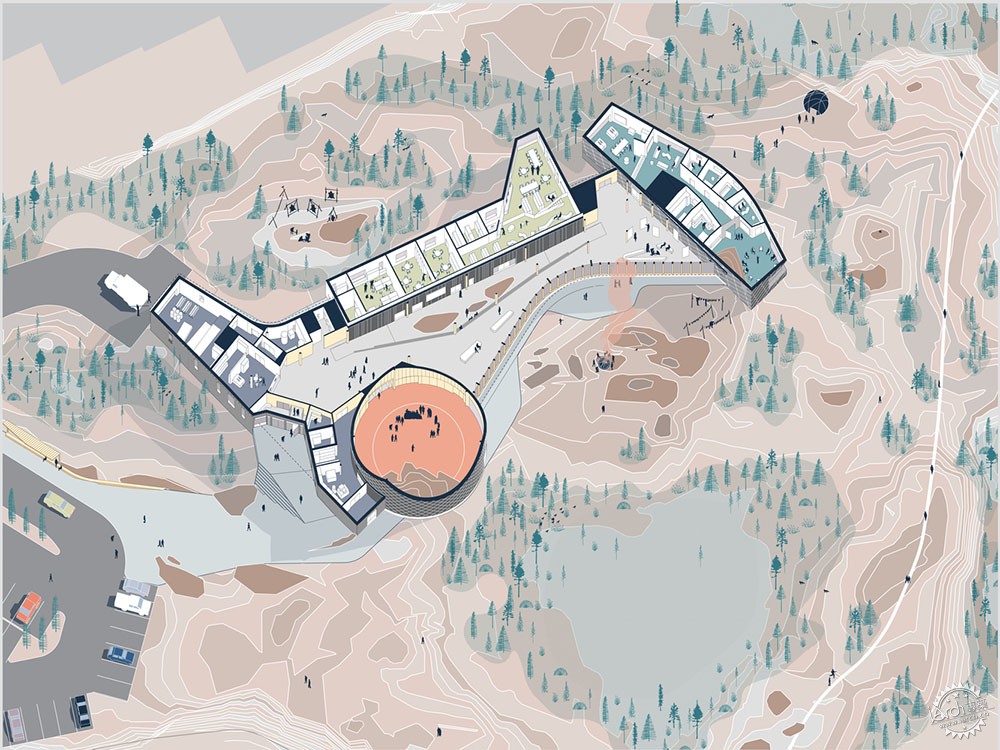

Lateral工作室于2003年由Sheppard与Mason White共同创立,是实验性的设计工作室,在建筑、景观、城市规划方面各有涉猎。工作室的理念是“将设计看做一种研究工具,在建筑环境中呼应当前的迫切问题”,并且所参与的项目有着广泛的背景,其中包含社会、生态,亦或是政治。在采访中,Lola讨论了在公共领域、基础设施、环境空间等方面,建筑与社区的整体塑造方式。

EB:能和我们说说Lateral工作室及其理念吗?

LS:自从工作室成立以来,我们致力于建筑学深度与广度的探索,面对文化和技术的不断发展,新类型也不断地出现,诸如城市、景观、建筑等学科的交叉也不断增多,我们探究设计发展的未来前景,拓宽建筑设计的各项领域。对于许多为建筑师们所忽略的研究区域,我们也很有探究的兴趣,在工作的早期,我们研究物流与远郊城市主义,这些问题在当时更多偏向理论研究,而非设计实践,更广泛地说,我们还探索了公共空间基础设施的设计契机。

Lateral Office, founded in 2003 by both Sheppard and Mason White, is an experimental design practice that operates at the intersection of architecture, landscape, and urbanism. The studio describes its practice process as a commitment to “design as a research vehicle to pose and respond to complex, urgent questions in the built environment,” engaging in the wider context and climate of a project– social, ecological, or political. In an interview with ArchDaily, Lola discusses how designing across the public realm, infrastructure, and the environment can shape architecture and community.

EB: Can you tell us more about Lateral Office and its mission?

LS: Since our founding, we have been interested in exploring the breadth of architecture, the emergence of new typologies in the face of changing cultural and technological realities, and the discipline’s intersection with urbanism, landscape, and infrastructure. We foreground design-research to broaden the issues that architecture engages with the intent to expand the agency of the profession. We are also interested in examining typologies and territories that have been overlooked by architects. Early in our practice we pursued questions of logistics and exurbanism (when this was primarily covered by theorists, but not designers). And, more generally, we explored the design opportunities of infrastructure in public realm.

我们对于环境和极端气候之间的建筑关系有着浓厚的兴趣,这也让我们意识到了建筑对于北极的作用。近期,我们继续探究了这些内容,研究在乡村和偏远地区的建筑作用,在这些地区,当地的地理环境和气候能够影响文化与经济的发展,而这些现状也让我们开始考虑战略性的干预网络,这个网络相较于单一的建筑而言能有更进一步的影响。在Lateral工作室,我们应用了大量的格式与平台,其中有书籍、展览、会议、城市设施、设计研究,共同探讨这些问题,也让我们更加明确,有时候,一座建筑并不够。

Our long-standing interest in architecture’s relationship to environment and extreme conditions led us to architecture’s role in the Arctic. More recently, we expanded this to look at the role of architecture in rural and remote communities, where geography and climate are central in shaping culture and economy. These conditions provoke us to think strategically about a network of interventions that might have larger impact than a singular building. Within Lateral Office, we have used numerous format and platforms—books, exhibitions, conferences, urban installations, design-research work—to explore these questions. Sometimes a building is just not enough.

EB:那么你为什么选择学习建筑学呢?

LS:我来自建筑家庭,那是我的父亲和我的祖父。我的父亲在加拿大蒙特利尔麦吉尔大学工作教书大约40年,我也在这里学习,而且,在二战中,我的父亲幸免于难,他也是一位建筑师,他被关押在集中营的时候,德国人甚至让他画建筑的草图。我的父亲和祖父生活的年代里,当时的建筑发展很乐观,能够促进社会的变革。因此我也选择学习建筑,我们当时每天都会谈论这个话题。

今天,我始终坚信建筑的重要作用,但是社会和政治领导者似乎并没有意识到建筑对于巩固社会环境方面的关键作用,其公共功能得以低估,并且通常和资本主义、社会利益密切挂钩,我们的作品也来源于这样的思路,即勇于提出问题,不断地拓展学科的范围。

EB: Why did you choose to study architecture?

LS: I come from a long lineage of architects – my father and my grandfather. My father practiced and taught for forty years at McGill University in Montreal, where I studied. More strikingly, his father’s life was spared during the second World War because he too was an architect. While he was interned in five different concentration camps, the Germans employed him to draft buildings. My father and grandfather lived in an era of immense architectural optimism, when architecture was seen as socially transformative. So in some ways studying architecture was already chosen for me. It was talked about at the dinner table every night, and it was all around me.

Today, despite my unfailing belief in the importance of architecture, it seems as if society and our political leaders fail to recognize the critical role architecture plays in cementing a strong environmental and social contract. Design and the public realm are under-valued, and so often tied to capitalist and corporate interests. Our practice was then born out of a desire to be able to ask questions fearlessly, like when we were students, to test the limits of what the discipline could reasonably engage in.

EB:在教师和建筑师的背景下,你认为学术和实践的关系是什么呢?

LS:对Mason和我而言,教学、研究、实践密切相关,我们的设计和研究来源于我们的作品和教学。对我们来说,教学是个有效的平台,能够激发各个学科之间的问题,促使学生探索全新的领域,以及全新的分析与记录模式,亦或是描述问题的方式,还能够在专业领域范畴承担各项风险。我们时常在教学和实践中探索相似的领域,其中包含地理、数据,以及方法,但是我们并没有把专业项目列入教学大纲之中,我们认为,让学生负责某个项目,而不是强行让他们学习会更有效一些。对建筑师而言,学习很重要,他们需要为自己的设计方案负责,我们也可以从教学中获益,让他们在思考和工作中有所收获。教学和实践是互补的策略,我常常让学生们在旅行中进行设计与研究,他们去过诸如纽芬兰、格陵兰岛等地区,和当地的居民沟通了解,学习当地的文化,了解社会背景,这不仅仅针对建筑师,也针对其他设计成员。

EB: You have a diverse background in teaching and as an architect. What do you believe is the relationship between academia and practice?

LS: For Mason and I, teaching, research and practice are deeply intertwined. Some of our design-research pursuits originate in our practice and some originate in teaching. Teaching is an effective platform for us to provoke disciplinary questions, to push students to explore new geographies, new modes of analysis and documentation, new ways of spatial storytelling, and to take risks that can be more difficult in the professional world. We are often exploring similar territories–whether geographic, scalar, or methodological—within our teaching and our practice, although we never bring a specific professional project into a studio syllabus. It is always more effective to teach in a manner that the project belongs to the student, not to the professor. It is important to the education of the architect that they bear the burden of responsibilities for their design decisions. There is also an immense amount we gain from teaching, learning from the next generation and how they think and work. One aspect in which teaching and practice overlap is through travel. I have taken students on design-research travel to Nunavut, the Yukon, the Northwest Territories, Newfoundland in Canada, and Greenland. Travel, and engaging with local residents, community leaders, and understanding firsthand local conditions, landscape and culture is an important education opportunity not only as architects but as design citizens.

EB:你最近完成了哪些项目呢?

LS:我们现在正在做很多事,比如一本书、一场展览、设计研究项目、建筑项目,旅行城市装置。

我们的脉冲跷跷板项目得到了很多关注,目前已经在全球四十多个城市中展出,我们也在开发一些临时设施,希望能够在特殊时期呼应公共空间。

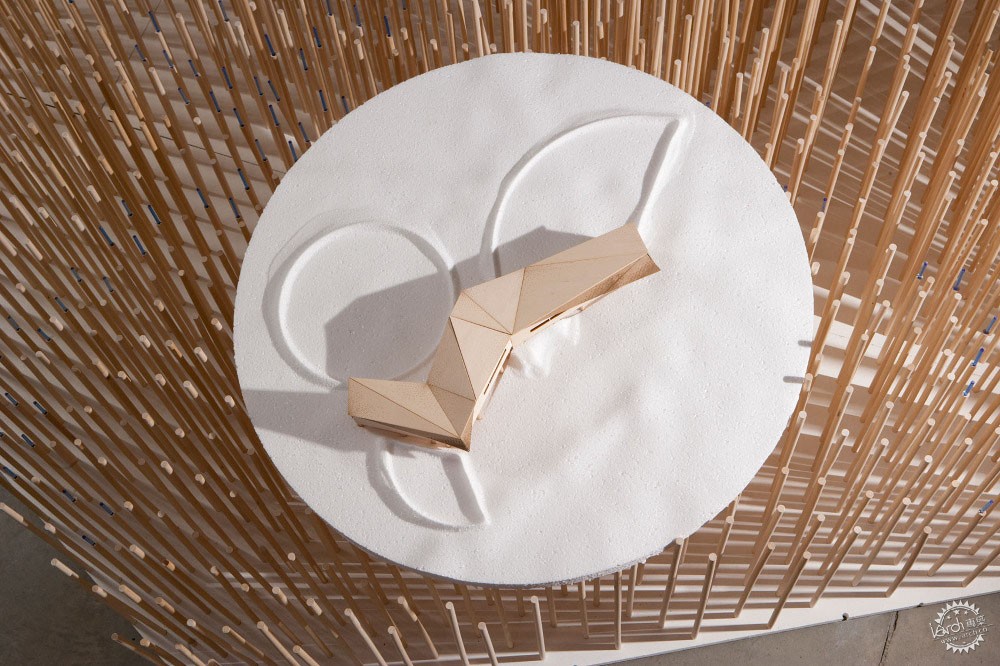

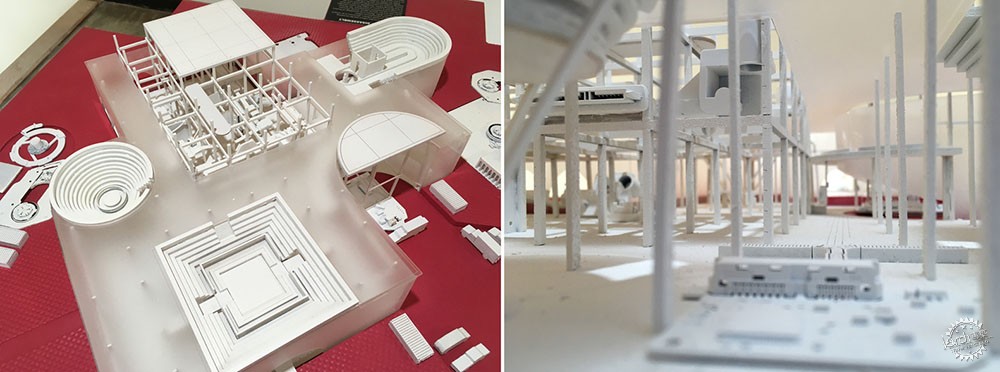

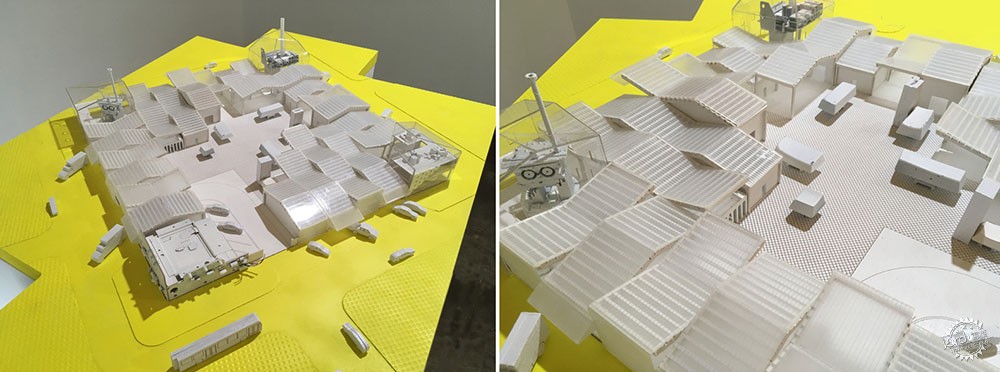

在设计研究方面,我们近期完成了奥斯陆建筑三年展的展览项目,标题为“繁荣与萧条:对于建筑与退化的思索”,这个项目的重点在于大西洋纽芬兰岛,我们花了几个月的时间和当地的社区人员进行沟通交流,这些人员都经历了城镇的繁荣与萧条,我们还研究了自上世纪50年代以来政府所试行的各种经济政策,随后我们开发了一套适用于当前社会与经济发展的空间类型,目的是建立稳定的城市结构,并且不需要依赖经济的发展。

EB: What are some recent projects you’ve worked on?

LS: We are working on a wide range of things right now: a book, an exhibition, design-research projects, a few building projects, and a traveling urban installation.

Our Impulse seesaw project has gotten far more attention than we ever anticipated and has been presented in every continent and over 40 cities world-wide. We are developing some temporary installations that attempt to respond to public space in the era of COVID.

In terms of design-research projects, we recently completed work on a project entitled Boom/Bust: Speculations on Architecture and Degrowth for the Oslo Architecture Triennale,which focused on rural Newfoundland, an island province in the Atlantic. We spent months speaking to community members in towns that had experienced dramatic cycles of economic boom and bust, as well as researching various economic catalysts that provincial governments have attempted since the 1950s. We then developed a set of spatial and programmatic typologies that leveraged existing social and economic practices, arguing for a “steady-state” architecture rather than the dependence on economic growth.

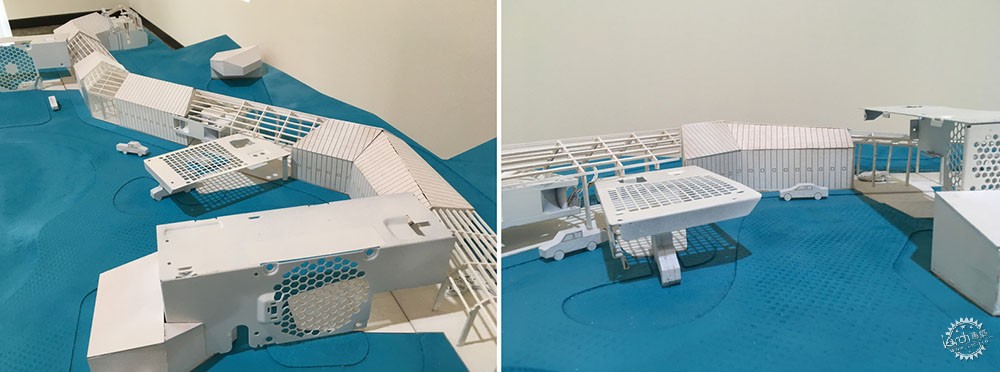

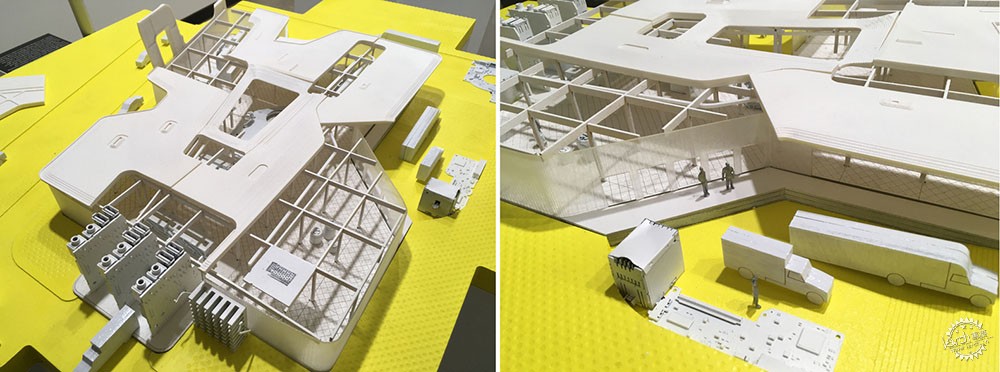

除此之外,我们还和加拿大多个当地社区共同合作开发项目,其中有努纳武特地区、西北地区、安大略地区等等,这些项目能够改变我们的工作方式,从传统文化中收获知识,并且重新建立我们对合作设计的信念,从而将建筑的历史遗产力量转变为文化发展的工具。我们正在写一本新书,其中包含有几个设计研究项目,更加细致地研究了“空间环境”的概念。这本书探讨了研究行为的重要作用,它促进了建筑环境的建构,挖掘设计思维中的连续潜力,强调多量化思维的重要意义。

除此之外,我们也在进行关于北极地区住房的全新研究项目,这个项目是我们和弗吉尼亚大学北极设计小组的合作,由于疫情的影响而延迟了,它也许会出现在2021年5月的威尼斯双年展上。

We are also working on several projects in partnership with Indigenous groups in various communities of Canada – Iqaluit (Nunavut), Yellowknife (Northwest Territories), and most recently, the Michipicoten First Nation in Wawa (Ontario). These projects are really changing how we work, learning from traditional knowledge, and reaffirming our belief in collaborative design processes in order to shift the historical legacy of architecture as a colonizing force to be instead a tool of cultural empowerment. We are also working on a new book, which consolidates several design-research projects, looking more closely at the notion of “spatial milieu.” The book explores the role of research as a tool for constructing new narratives for architecture’s environment, the potential of seriality in design thinking, and the importance of multi-scalar thinking.

We are also working on a new design-research project on housing in the Arctic. It’s a collaboration with the Arctic Design Group at University of Virginia, and should be ready, after a much-needed pandemic delay, for the Venice Biennale opening in May 2021.

EB:你喜欢什么样的项目呢?为什么?

LS:我们在设计竞赛中获得了一些成功,但是很快我们就发现自己对自我生成的项目很感兴趣,这些项目与资金无关,但是对当下的实践更具有反应的要求,我们在进行此类项目的时候,所采取的策略更需要时间和关键要素,但是这就涉及到资金了,我们需要在研究和艺术方面具有一定的创造精神,这样我们就能够自由决定项目的各项参数,我们不断地和不同类型的伙伴们合作,尤其是在偏远地区的项目中,这样的结果很令人满意,我们的许多合作伙伴都常常被忽视,因此我们能够通过设计研究而对社会产生一定影响,提升事业的发展效率,除此之外,我们也可以不断地探索具有包容性的工作方式,这让我们的作品使用率更高,同时也让我们自身时刻保持敏锐的洞察力。

EB: What type of projects do you enjoy working on most, and why?

LS: We began our practice with some fortunate early success in design competitions, but soon found that we took more interest from self-generating projects, which would be more speculative and reactive to current events and unattached to capital. When we generated the project ourselves, it gave us the ability to choose the duration, format, and criticality of our approach. Of course, this requires funding, and we have also had to be creative about pursuing research and arts grants that give us, and our collaborators, the freedom to determine the parameters of the project. Increasingly, we are working with community partners and other design collaborators, particularly in remote and rural communities. This has been very satisfying, as many of our community partners have long been overlooked, so we can have a social impact through design-research and elevate the cause of our partners. Equally, we can explore formats for working that are inclusive and participatory, which has made work more open to use and interpretation. This is exciting and keeps us alert for opportunities.

EB:在你的工作室里,生态、景观和建筑时常相互交融,那你的设计过程是怎么样的呢?

LS:我们常常起始于广泛的研究,目的是表达隐藏的真相。我们的许多项目都针对于建筑的外部因素,例如经济、文化、社会、后勤等方面,而我们的多个初步研究也在这个领域之外而进行。建筑属于生态范畴,其中的能量、物质,以及建筑的生命周期都能够证明这一点,但是我们也深入地了解了一些具有价值的元素,如电子垃圾、乡村经济,以及北方基础设施等等,相关案例有“拆卸状态:关于电子产品、有毒物质、相关领域的推测”。我们花费了几个月的时间来研究电子废物在全球范围内的循环、法律方面的漏洞、方案层面的非正式创新等方面。这也揭露了废物层面的“有毒殖民主义”,在这个层面中,废物无法看见,它们常常去往经济发展程度暂时落后的国家和地区,这个研究也表达了人们可以从源头截取电子垃圾,并且构想全新的建筑类型、经济发展,亦或是全新的基础设施。我们认为,电子垃圾的文化潜力巨大,而建筑能够帮助其发生转变。

EB: In your office, ecology and landscape are often intertwined with architecture; what does your design process look like?

LS: We typically begin with expansive research with the intent of uncovering hidden truths. Many of our projects are interested in the extrinsic forces—economic, cultural, social, logistical or other–that shape architecture, and much of our initial research originates outside the field. We would argue that architecture is complicit with ecology. The embodied energy, material narratives, and ultimately architecture’s ruin demonstrate that. But also we are interested in the larger understanding of worthwhile dilemmas such as electronic waste, rural economics, or northern infrastructures. For instance, in States of Disassembly:Speculations on Electronics, Toxicity, and Territory, we spent several months researching how e-waste cycles work globally, where the legal loop-holes were, what informal innovations were already happening on a programmatic level, and so forth. This exposed a “toxic colonialism” within the waste stream that sends waste “out of sight”—often to economically compromised nations. The research revealed opportunities to intercept e-waste at the original source, and imagine new building typologies, new economies, and even new types of cultural infrastructure. We think this could allow greater visibility, appropriation, and participation of culture in e-waste and architecture has the potential to help make that transition.

EB:在多伦多工作、在滑铁卢教书,这些经历是否对你的作品有影响?

LS:多伦多给我们带来了良好的家庭基础,我们可以从文化和能力的角度而进行全日制的教学。但是我们的作品在多伦多却不多,尤其是因为这座城市对于建筑的传统理解方式,我的家乡在蒙特利尔,我们有了彼此之间的吸引和互动,蒙特利尔是北美最好的建筑城市,它将对建筑环境的塑造看做是一种重要的文化行为,而不仅仅是简单的经济产物。我其实认为我们是属于加拿大的建筑实践,但是具体来说不是多伦多的建筑实践,它常常意味着传统。关于地区或是民族影响的问题我们也在项目和工作中探讨过,在当今这个时代,全球化的趋势巨大,不同地区的场所特征常常被抹去,那么地域建筑和空间实践又意味着什么呢?我在“滑铁卢建筑”任教15年,这里就像是被隐藏起来的宝石,这里有着强烈的社会与文化感知,培养出的学生极具独立的思维与表达能力,而作为合作院校,我们的学生学习期间在全球各个公司工作2年,我们也有幸聘请了许多来自滑铁卢和多伦多大学的优秀学生。

EB: Practicing in Toronto and teaching in Waterloo, how does the local region influence your work?

LS: Toronto has provided us with an excellent home base—both culturally and in terms of our ability to teach full-time at strong but very different institutions. However, very little of our work has been grounded specifically in Toronto, not least because the city is largely committed to a rather conventional understanding of architecture. We have had more traction and interaction in my home city of Montreal, which I think is one of the best cities in North America for architecture–committed to the built environment as an important cultural act, not simply an economic product. I do think we are very much a Canadian practice, but perhaps not specifically a Toronto practice, in what that would conventionally imply. This question about local or national influence is also something that we explore in our projects and work: What does local (vernacular) architecture and spatial practice mean today, in an era of powerful globalizing forces which tend to erase particularities of place? Waterloo Architecture, where I have taught for 15 years, is a hidden gem as an institution. It has a strong social and cultural conscience, producing remarkably thoughtful and articulate students. As a co-operative school, our students work for two years during their undergraduate studies, in firms all around the world. And we have been lucky to hire remarkable students from both Waterloo and University of Toronto within Lateral Office.

EB:目前有哪些建筑类型你还没有尝试过,但是想要尝试的呢?

LS:我们目前正在和加拿大北部的当地伙伴合作社区健康医疗项目,他们正在逐步发展,因此在完成后,人们就能够感受到这些非常棒的项目。

但是当前的问题则要求建筑师扮演全新的角色,这个问题也应该得以探索,我们的世界经历了一系列的社会问题,例如证券问题、流行疾病,亦或是黑死病等等,再回归到商业环境中,这看起来显得有些苍白。2020年似乎是一个重要的年份,它说明了建筑也无法与当前的社会状况完全脱离。我们也希望能够找到这样一种方法,即系统地呼应我们的运行方式,这其中也包括研究设计项目。我们努力在解决各式各样的问题,希望能够在紧迫的事件中找到平衡点,我们是空间设计师,我们需要直接应对一系列的反应,然后再从更长远的角度,来审视城市及其基础设施给人们带来的反馈与思考。

EB: Are there any project types you haven’t had the chance to take on yet, but would like to?

LS: We are currently working on two community health and wellness projects with Indigenous partners in the Canadian North. They are starting to move forward, so it would be wonderful to see these projects when they are built.

But current events are calling for new roles for architects that should also be explored. It is looking increasingly ignorant to return back to business-as-usual after the radical transformation of our world from authoritarian regimes, pandemics, and the urgent social upheaval of the Black Lives Matter movement. 2020 is looking like a critical line in the sand for the design professions, since even Architecture is not insulated from these urgent issues. We too will want to find a way to respond both systematically in how we operate, but also in the scope of design-research projects. We are working through some of this now, hoping to find a balance between urgency and relevancy. There is probably a more immediate set of responses we as spatial designers need to grapple with, and then longer term ones that examine a more radical rethinking of the city, and its collective infrastructure.

EB:当你看向未来的时候,你认为应该在建筑师和设计师脑海中占据主要位置的想法是什么呢?

LS:考虑到当前的世界和当地的状况,也许这个问题应该改成我们不应该关注什么,这个学科是一场永恒的拉锯战,存在于内省和隔离主义态度之间,其中的观点也是需要容纳来自其他学科的知识和问题,近期的事件已经明确了建筑学需要不断地延伸其研究范围。

我们刚刚完成一篇文章,以过去六十多年的角度来重新审视建筑行业的“激进传统”。激进传统可以被理解为是利用空间的实践来揭露不公正的现象,促进社会包容和政治动机的设计作品的发展。其中提问到,在激进主义传统中,谁拥有特权和发言权呢?建筑行业的包容性逐步扩大,其对于性别、种族、文化、人口代表性方面也不断提升,更多的人们得以发声。在政治方面,激进主义可以理解为直接地使用,常常以对抗性的行为来支持某种状态,其中可以是社会、政治、经济、环境等不同角度,而在建筑方面,实践行为的动机多种多样,它可以是某种手段,用于规避客户与建筑师之间的传统权力结构,也为缺乏代表性的团体而发声,亦或是促进人们对城市或环境问题进行深入探讨与思考,这种手段也常常否认建筑创新的社会与政治利益。建筑行业的激进主义遗产似乎比以往任何时候都更加迫切。

我们很幸运的是,拥有优秀的合作团队,负责我们的各项工作,Lateral工作室目前由合伙人Lola Sheppard、Mason White、Kearon Roy Taylor领导,还有工作人员Irina Rouby Appelbaum、Haiqa Nisar,以及Sam Shahsavani。

EB: As you look to the future, are there any ideas you think should be front and center in the minds of architects and designers?

LS: Given current world and local events, perhaps the question is what should we not be looking at? The discipline is in a perpetual tug of war between an introspective and disciplinary isolationist position and an expansive view that seeks to embrace knowledge and problems from other disciplines. Recent events have crystallized architecture’s need to expand its agency and potency.

We’ve just finished writing an essay looking at the current state of the “activist tradition” in architecture, looking through the lens of the past sixty years (to be published in the next issue of Perspecta). The activist tradition can be understood as the use of spatial practice to expose injustice and foster socially inclusive and politically motivated design. It also asks: who has the privilege and the voice in the activist tradition? As the profession expands its gender, racial, cultural and demographic representation, a wider range of voices are participating on behalf of those under-represented in spatial and aesthetic discourse. In politics, activism is understood as the use of direct, often confrontational action in support of a cause, whether social, political, economic or environmental. In architecture, how action is practiced is as varied as its motivation: it can serve as a means of circumventing traditional power structures of client-architect, as a means of giving voice and agency to under-represented groups, or to catalyze attention and discussion to important urban or environmental issues, often denied the social and political benefits of architectural innovation. This legacy of activism in architecture seems more pressing than ever.

We have been incredibly fortunate to have an amazing team of collaborators who lead our research and work. Lateral Office is currently comprised of partners Lola Sheppard and Mason White, with Kearon Roy Taylor (Associate), and interns Irina Rouby Appelbaum, Haiqa Nisar, and Sam Shahsavani.

图片:Courtesy of Lateral Office

|

|