Dominique Coulon & associés. Image © Eugeni Pons

为老年人而设计,请着眼未来

To Design for the Elderly, Don't Look to the Past

由专筑网李韧,王帅编译

无论是社会、经济、科技、政治方面,只要世界产生了重大变革,那么建筑也需要进行相关的改变。政府的政策能够为设计带来新机遇,比如伦敦各地的高质量社会住房数量的增加。科技进步的影响较为明显,但是社会的变革对于建筑行业来说同样重要。

人口的变化亦如此,当前,人类处在人口模式的巨大转变之中。在2015年,全球65岁以上的人口约占8.5%(约6.17亿),根据预测,到2030年,这一比例将会上升至12%,而到了2050年,则会上升至16.7%。纵观历史,这个数字始终保持上升趋势,因为医学的成就延长了人类的寿命,因此全球老龄化的现象较为明显。而在一些出生率较低的国家,这一问题更为险峻,例如日本。因此人们必须重视老年人的社会设施。

当考虑这些数据的影响时,建筑背景之中的自然假设则是需要考虑医疗健康、医院设计,以及城市入口。然而,这却忽略了一个愈发严重的问题,那便是社会的孤独性。在英国,年龄在75岁以上的老年人有半数都保持独居状态,大约有11%的老年人每个月与家人朋友的会面不到一次,欧洲也是如此。

老年人中的慢性孤独现象非常普遍,经研究,这会影响到健康状况,例如残疾、心脏病、中风、痴呆等病症。那么建筑师应当从源头上解决这个问题,同时帮助他们提升生活质量。本文便阐述了如何通过设计的方式解决这个问题,以及建筑师和行业领导者所应该做的工作。

近年来,建筑师和开发商都开始思考老年人的住房问题。许多研究机构都在研究现代老年人的需求,其中包括RIBA与New London Architecture事务所。新策略注重光线、现代化、敏感设施等等,这与传统方法相反。在现代方案中,无论空间感受与传统习惯,部分解决方式对于居民来说都适用。现代退休社区也为人们提供了互动的契机,但是同时又让居民保持独立的空间。

When the world undergoes major changes (be it social, economic, technological, or political), the world of architecture needs to adapt alongside. Changes in government policy, for example, can bring about new opportunities for design to thrive, such as the influx of high-quality social housing currently being designed throughout London. Technological advances are easier to notice, but societal changes have just as much impact upon the architecture industry and the buildings we design.

The same is true of changes in demographics, and we are in the midst of a monumental shift. In 2015, 8.5% of the population of the world was aged 65 or over (617 million people). This is predicted to grow to 12% of the population by 2030, and to a staggering 16.7% of the population by 2050 [1]. Historically, this percentage has steadily grown but dramatic advances in medicine are allowing people to live longer, creating aging populations across the globe. This problem is compounded in countries where the birth rate is also incredibly low, as is the case with Japan. We must reevaluate how the elderly are treated within society.

When thinking about the impact of these statistics, the natural assumption within the context of architecture is to think about medical care, hospital design, and accessible cities. However, this overlooks an emerging and serious problem: loneliness and social isolation. Within the UK, 51% of those aged over 75 live alone, and 11% of older people are in contact with friends and family less than once a month [2]. Similar results are present across Europe.

Chronic loneliness within the elderly population is incredibly prevalent and a significant number of studies have been conducted looking at the measurable health impact it has, such as creating a higher risk of disabilities, heart disease, strokes, and dementia. Architects can help tackle loneliness at the source and dramatically help increase the quality of life for a portion of the population who are often isolated. This article explores how good design can help further this cause, how architects have combated this previously, and what the industry leaders are doing now.

In recent years, architects and developers alike have begun to rethink how housing for the elderly should be treated. Multiple panels discussing and studying the needs of the modern older person have been held, including with RIBA and New London Architecture. The new approach features light, modern and very sensitively designed property - the exact opposite of the traditional image. In these schemes, part of the solution is making the housing desirable to residents regardless of perceived or traditional tastes. Living in modern retirement communities provides an opportunity for engagement and interaction while beginning to shed this stigma, and allowing residents to retain their independence.

Pilgrim Gardens / PRP . Image © Tim Crocker, via Matthew Usher

Pilgrim Gardens / PRP . Image © Tim Crocker, via Matthew Usher

老龄化人口创新小组(Housing our Ageing Population Panel for Innovation——HAPPI)会议最初于2009年召开,他们的报告成为了行业标准,其中包括了来自欧洲的多个高质量研究案例,而后来的问题不仅仅说明了研究小组的调查结果,还结合了实施方针,之中的建议覆盖广泛,其中有建筑的空间标准、日光、健康护理的适应性需求,也有公众积极参与的社会问题。这些内容都较为重要,因此能够与建筑标准相结合。

PRP已经成为了这一领域的领导者,并且从HAPPI的报告中获取大量的信息。他们设计的Pilgrim花园项目在2012年至2014年间获得了许多奖项,同时也展示了一些来源于HAPPI的设计建议。双层公寓环绕着花园和景观,公共柱廊起到了循序渐进的作用,公寓有着内置滑动玻璃门,使用者全年都能够感受阳台上的户外美景。

The Housing our Ageing Population Panel for Innovation (serendipitously acronymed HAPPI) was originally held in 2009, and their reports have since become industry standard. The original 2009 report featured multiple high-quality case studies from throughout Europe, and subsequent issues featured not just the panel's findings but guides for implementation. Advice includes ranges from the architectural (generous space standards, daylight, and adaptability for ‘care readiness’) to the social (engaging positively with the public.) It is the latter part of this range that is most crucial and can be combined with architectural standards.

PRP have become leaders within this field and heavily draw upon this advice from the HAPPI reports. Their Pilgrim Gardens project won multiple awards between 2012-2014 and features several of the design features advised by HAPPI. Double-aspect flats encircle communal garden spaces of hard and soft landscaping, and a shared colonnade acts as a slow circulation space. In-built sliding glass doors to allow the use of the balconies year round.

Nursing and Retirement Home / Dietger Wissounig Architekten. Image © Paul Ott

Nursing and Retirement Home / Dietger Wissounig Architekten. Image © Paul Ott

Nursing and Retirement Home / Dietger Wissounig Architekten. Image © Paul Ott

Nursing and Retirement Home / Dietger Wissounig Architekten. Image © Paul Ott

Nursing and Retirement Home / Dietger Wissounig Architekten. Image © Paul Ott

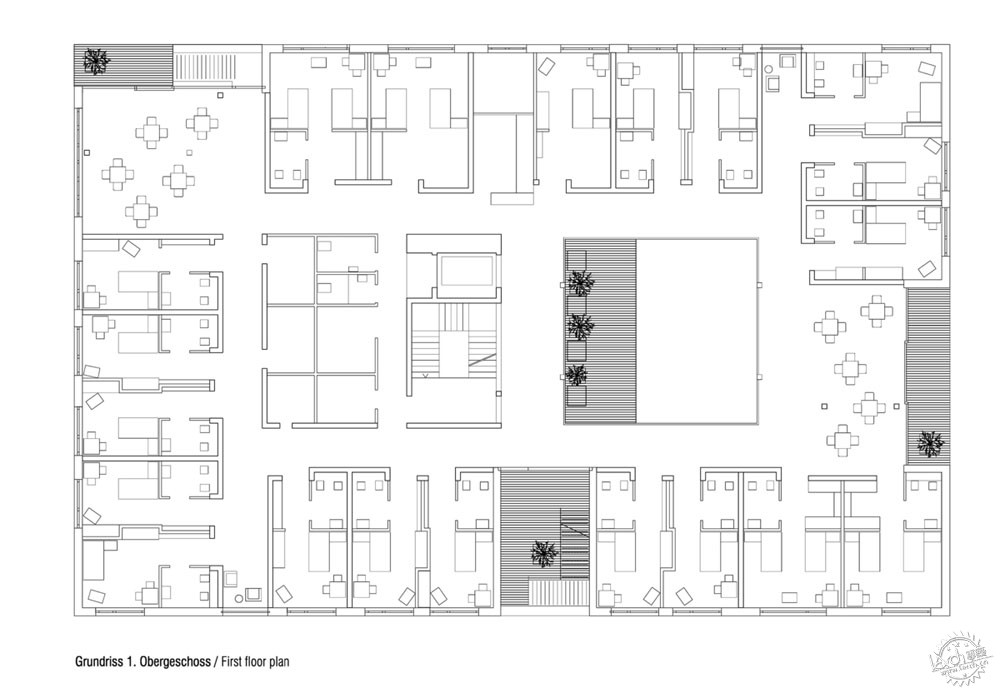

Nursing and Retirement Home / Dietger Wissounig Architekten. Image Courtesy of Dietger Wissouning

Nursing and Retirement Home / Dietger Wissounig Architekten. Image Courtesy of Dietger Wissouning

Nursing and Retirement Home / Dietger Wissounig Architekten. Image Courtesy of Dietger Wissouning

Dietger Wissounig Architekten事务所的奥地利疗养院项目的内部也采用了类似的手法,更多地关注那些需要护理的人群,建筑师应用了轻质木材,形成柔软温暖的空间环境。设计师避免了双层走廊,这让空间呈现出欢迎感,同时让流线更加通畅。

While focusing more on those requiring care, Dietger Wissounig Architekten’s nursing home in Austria employs a similar effect internally and is incredibly light, liberally using timber and wood within to create a soft and caring environment. Double-stacked corridors are again avoided, allowing the circulation to be inhabited socially as inviting spaces.

The Architect / LEVS architecten. Image © Marcel van der Burg, via Matthew Usher

报告还强调了多功能空间的作用,居民们可以在这里聚会,同时也起到了社区中心的作用,在The Architect in Utrecht,需要护理的老年公寓和公共空间、托幼中心结合在同一座建筑之中。来自挪威Haptic和伦敦Witherford Watson Mann的项目同样强调了社会联系的必要性。这些项目在邻里、儿童、当地社区之间都建立了必要的联系,而这些联系则来源于花园、公共设施、商店,以及公共广场。

The report also highlights the need for multipurpose space where the residents can meet and which could possibly act as a hub for the local community. At The Architect in Utrecht, residences for the elderly requiring care are stitched into the building with the rest of the housing alongside communal spaces and the nursery. Similar projects by Haptic in Norway and Witherford Watson Mann’s almshouse in London also stress the need for social connection. These projects share spaces between neighbors, school children, and the local community through gardens, allotments, shops, and public squares.

Senior Center of Guangxi / Atelier Alter. Image Courtesy of Atelier Alter, via Matthew Usher

城市愈发承认老年人口的变化需求,“Campaign To End Loneliness”为解决多方面问题,建立了3个方法的框架,其中包括个人措施、社区行为,以及整体系统策略。为了应对更加广泛的挑战,曼彻斯特成为了英国的第一座爱老城市,这是世界卫生组织的倡议,全球范围内的多座城市都赞同这项提议。该倡议包括改善交通、住房、健康服务问题,同时也强调了公众参与的必要作用。

建筑师在这些新建议中起到了主导作用。在曼彻斯特,“爱老设计团队”协助设计当地公园,来满足更多年龄层面的需求,它们仔细聆听老人们的建议,解决问题,列出设计方针。RIBA前任总裁Stephen Hodder认为,这些团队进行了“迫切需求的讨论,沟通如何为老年人塑造更好的景观环境”。

Cities have begun to acknowledge the changing needs of an aging population. The ‘Campaign To End Loneliness’ has established a framework of three methods in order to address the multifaceted issue: individual intervention, neighborhood action, and a whole system approach. To help combat the wider scale challenges, the city of Manchester has become the UK’s first ‘age-friendly city’ [4], a World Health Organisation initiative which several forward-thinking cities across the world have subscribed to. The key priorities of the initiative include known benefits such as improvements in transport, housing, and health services, but also highlights the need for civic participation.

Architects can take a leading role in the design of new policy. In Manchester, the ‘Age-Friendly Design Group’ assists with designing local parks to be more age-friendly, listening to the elderly to inform good practice, and publishing of design guidelines. Stephen Hodder, a previous RIBA president, said that such groups open up a “much-needed debate on how we can start shaping the landscape of our built environment for our older age”.

Casa del Abuelo / Taller DIEZ 05. Image © Luis Gordoa, via Matthew Usher

除了城市规模,建筑方案同样能够满足需求。诸如墨西哥Casa del Abuelo的公共日间中心同样受欢迎,尤其是在西班牙和葡萄牙。该中心的设计模糊了室内外空间的边界,既开敞又现代。这大概是因为当地的气候,而这种趋势也似乎在表达一种流行策略。

中国的广西高级中心服务了大量人口,并且有着许多的活动空间。起伏的形态、木纹铝框百叶应用在诸如游乐场所、公园、室内游泳池、乒乓球室等空间中。老年人可以在这里进行社交与活动。

Outside of the city-scale, architectural solutions can also provide for a range of needs. Public ‘day-stay’ centers, such as the Casa del Abuelo in Mexico seem particularly popular (especially in Spain and Portugal.) The design of centers such as these is often strikingly modern and open, blurring the distinction between inside and out. This can partly be attributed to the temperate climates these projects are located in, but the prevalence hints at an emerging approach.

The Guangxi senior center in China, serves an atypically large population and features a range of activities and spaces to accommodate this. The undulating form, clad in wood grain aluminum louvers, includes everything from game courts and gardens to an indoor swimming pool and table tennis rooms. This haven of activity attempts to engage the elderly in physical activity alongside social spaces.

Sant Antoni - Joan Oliver Library / RCR Arquitectes. Image © Eugeni Pons

Sant Antoni - Joan Oliver Library / RCR Arquitectes. Image © Eugeni Pons

Sant Antoni - Joan Oliver Library / RCR Arquitectes. Image © Eugeni Pons

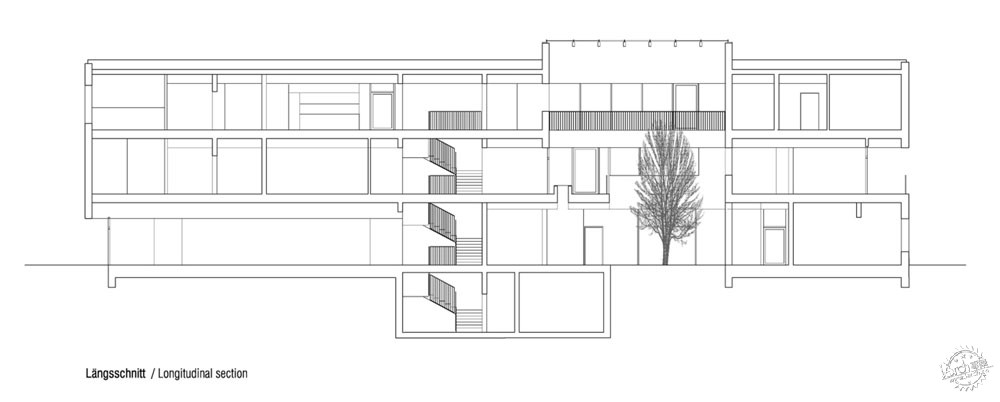

Courtesy of RCR Arquitectes. ImageSant Antoni - Joan Oliver Library / RCR Arquitectes

Courtesy of RCR Arquitectes. ImageSant Antoni - Joan Oliver Library / RCR Arquitectes

Courtesy of RCR Arquitectes. ImageSant Antoni - Joan Oliver Library / RCR Arquitectes

当这些建筑用作当地社区中心,而非单纯的单功能建筑时,一些目标便很容易达到。这种方法类似于The Architect in Utrecht,其中包括有住宅的多种类型,而且还可以和图书馆和学校结合起来。一个成功的案例便是由普利兹克获得者RCR Arquitectes设计的Sant Antoni - Joan Oliver图书馆。

该项目位于巴塞罗那的城市街区之中,建筑环绕中庭排布。图书馆形成了建筑的公共区域和主要规划元素,这些部分位于两座公寓建筑之中。社区空间则位于庭院的一侧,面向公共场所,这保持了一定程度的“安全范围”,环绕了一个核心部分,将项目统一起来。

Particular success can be found when positioning these centers as hubs for the local neighborhoods rather than simply as single-purpose structures. This method is similar to The Architect in Utrecht, This can include proximity to other types of housing (such as The Architect) but can also be integrated with libraries or universities. A successful example of this is Sant Antoni - Joan Oliver Library, by Pritzker Prize-winning practice RCR Arquitectes.

The project is nestled within one of Barcelona’s city blocks, wrapping around a central courtyard. The library forms the public face of the building and primary programmatic element, appearing to be suspended between two apartment buildings. The community space then occupies one wall of the courtyard and overlooks the public space. This maintains the perceived ‘safe space’ but places it firmly around a local hub, unifying the project into a coherent block.

JIKKA / Issei Suma. Image © Takumi Ota

JIKKA / Issei Suma. Image © Takumi Ota

JIKKA / Issei Suma. Image © Takumi Ota

Courtesy of Issei Suma. Image JIKKA / Issei Suma

JIKKA / Issei Suma. Image © Takumi Ota

JIKKA / Issei Suma. Image © Takumi Ota

最后一种方法便是促进年轻人和老年人之间的互动,这听起来是个奇怪的组合,许多人也正在对此进行研究,希望能够以安全可靠的方式在项目中贯彻这些理念。

本文在开头提到,日本的老龄化现象较为严重,人们平均寿命的增加和社会变革使得托幼中心和养老院的数量不断上升。因此,人们需要重新调整年轻人和老年人的不同对待方式,在这方面,日本已经努力了40多年。东京Kotoen儿童与老人设施是日本最为古老的老年综合设施,这座建筑于1976年投入使用。在这里有着双向的互动,例如老年人可以成为托幼中心的志愿者,而孩子们也可以参观疗养院的公共区域,他们还可以共同参加特殊活动。

A final method is to promote interaction between the young and the elderly. These may seem to be an odd combination of programmes, but significant research is being undertaken into this and the centers which currently subscribe to these ideals and offer them in a safe and secure way.

At the beginning of this article, Japan was noted to be one of the countries most impacted by aging populations going forwards. Increasing life expectancy and societal changes (leading mothers to work outside the home) has meant the numbers both nurseries and senior centers/retirement homes are increasing. There is clearly an opportunity to restructure the way care is delivered for both young and old - something Japan has already been doing for over 40 years. Kotoen, a “yoro shisetsu” (facility for the children and the elderly) in Tokyo, is the oldest age-integrated facility in Japan, having opened in 1976. Here, interaction cuts both ways: seniors can volunteer in the nursery, children visit the communal areas of the care home, and both join together for special events.

London Almshouse / Witherford Watson Mann. Image Courtesy of Witherford Watson Mann

对疗养院而言,这种安排也大有益处,两个人群都有着基本的需求,例如饮食、体育活动,以及公共空间,对于老年人而言,体育活动非常重要,这能够帮助他们保持活力。而老年人的益处便更加明显,这种布局方式结合了活动,将日常生活带入相对普通的场所之中。而对于孩子们而言,这能够促进他们的身心健康,并且对于老年人有着积极乐观的态度,同时削弱偏见。

西雅图托幼中心Mount St. Vincent便设置有国际学习中心,这有类似的益处,它能够帮助那些家失去老者的孩子们感受祖父母般的爱,更大程度地感受家庭生活。

令人惊讶的是,这对老年人的身心健康都有着很大的影响。英国布里斯托尔的St. Monica基金会便对此进行了研究,调查了在6个星期内对于居民的影响。研究结束时,大约80%的居民的灵活性和抓握能力得以提升,70%居民的抑郁倾向得以降低。

那么建筑师应当如何贯彻这些理念呢?孤独感的影响十分巨大,但是世界上的大多数案例都由事件驱使。因此建筑师需要应当构思全新的建筑类型来适应老年人和年轻人的共同需求,而不是单纯地对现有空间进行改造。人们都不喜欢生活在单一的环境之中,因此可以适当地进行创意性构思与设计。

When adjoined to care homes, the benefits of this arrangement make sense. Both share basic needs: the provision of meals, physical activity (in the case of the elderly, to keep them active and fit), and communal spaces for socializing. The benefits for the elderly are fairly obvious. The arrangement provides company and activity, bringing life into a space which can often become mundane. But there are notable social and developmental benefits to the children as well: it helps to promote a healthy and positive view of aging and helps counter any preconceptions about the less able.

Mount St. Vincent, a care home in Seattle, runs an ‘Intergenerational Learning Centre’ and endorses similar benefits, stating that it helps to provide a broader perspective of family life for the children who do not have grandparents active in their life.

Surprisingly, there is a dramatic and measurable impact of this upon the physical and mental health of the elderly. St. Monica’s Trust in Bristol housed a study into these benefits, measuring the impact upon the residents over a six week period. At the end of the study, 80% of the residents had improved their mobility and grip strength, and 70% has reduced their score on the scale of depression.

So how can architects begin to promote and further this idea? The impact upon loneliness of aligning these programmes together is dramatic, but the majority of the examples across the world are activity and event-driven. There is the opportunity to develop a new building type to house this program and best suit the needs of the young and old, rather than attempting to retrofit existing spaces. Neither senior citizens nor children want to live in a dull environment, so adapting the design creatively to suit the characteristics of their users is a wonderful opportunity rarely given.

Dominique Coulon & associés. Image © Eugeni Pons

Dominique Coulon & associés. Image © Eugeni Pons

Dominique Coulon & associés. Image © Eugeni Pons

Dominique Coulon & associés. Image © Eugeni Pons

Dominique Coulon & associés. Image © Eugeni Pons

Dominique Coulon & associés. Image © Eugeni Pons

|

|