希腊Stavros Niarchos基金会文化中心|Stavros Niarchos Cultural Centre_2008-16_Athens, Greece

“Beaubourg区的蓬皮杜艺术中心是热那亚港口的一艘船。”——与伦佐·皮亚诺的对话

“Beaubourg is a Ship in Genoa Harbor!”: In Conversation with Renzo Piano

由专筑网李韧,蒋晖编译

上世纪90年代中期,我从库珀联合建筑学院毕业之后,前往意大利参加一次工作室的竞赛,几番交流之后,一位参赛者直接过来问我,“你最喜欢的建筑师是谁?”于是我说出了我脑中出现的第一个名字,“伦佐·皮亚诺。”后来我意识到这好像是事实。曾经我去意大利热那亚参观过这位建筑师的办公室,切身感受了一下皮亚诺的作品。他的办公室位于Via Pietro Paolo Rubens 29海边山坡之上。在当时,他的作品得到了充分的表达,其最为知名的作品巴黎蓬皮杜艺术中心(Center Pompidou in Paris)已经建成。该作品于1971年至1977年由皮亚诺与罗杰斯合作完成,另外还有1982年至1986年的休斯敦梅尼尔艺术馆( The Menil Collection in Houston)、意大利圣尼古拉球场(1987至1990年)、日本关西国际机场(1988至1994年)、瑞士巴塞尔拜尔勒基金会博物馆(1991至1997年)、芝柏文化中心(1991至1998年)。皮亚诺的作品很平衡,但是也很大胆,看上去设计精致,与周围环境结合得很融洽,几乎无可挑剔。除了基本的功能之外,其建筑作品有时会抬高一些,从而能够吸收大量的阳光,同时构成公共场所。其优美的线条与细腻的细部使建筑看上去就像是一件艺术品。

我们在纽约的皮亚诺作品交流会上进行了长达一个半小时的交流,地点是在其2015年的作品纽约惠特尼博物馆的对面。这座博物馆并没有他早期的作品那样惊艳,但是它依然极具吸引力,让人们每一次来到这里,都能有不同的发现,无论是建筑内还是外,开放的露台和楼梯环绕建筑,拥抱着城市。我们在这了沟通了这位建筑师的早期作品,以及他对于美学、直觉、想象力、叛逆性的反应与思考。

Vladimir Belogolovsky(下文称为VB):你曾经在米兰理工大学学习建筑,你曾经发表了一些关于制造与模块化轻质结构的文章。那么你能谈谈你是如何对建筑感兴趣的呢?

伦佐·皮亚诺(下文称为RP):我成长于工人家庭,我也一直想成为一名工人。我直到开始念书才知道建筑学,在我的家乡,意大利热那亚,那里没有建筑学专业,我当时又很想离开家去其他地方看一看,因此我就去了米兰。但是这始终是关乎建筑的设计过程,在当时的建筑主要是经过模块化的施工的,而让建筑更加经济一些,同时这也是一种很好的思维方式。模块化是一种秩序,而生活却有些混乱,即使是伟大的音乐家也需要通过记录想法来表达概念。因此,我的想法就变得较为理性与清晰。在学生时期,概念几乎不受限制,因此我们关心的是道德、经济、以人为本,亦或是建筑的尺度。

Right after graduating from the Cooper Union School of Architecture in the mid-90s, I headed for Italy to participate in a workshop competition. Over beers, a fellow competitor confronted me point blank, “Who is your favorite architect?” Caught by surprise, I uttered the first name that came into my mind, “Renzo Piano.” Shortly after, I realized it was true. On that same trip, I went to Genoa to visit the architect’s office, perched on the slopes of a hill above the sea on Via Pietro Paolo Rubens 29 to touch, sniff, and discuss Piano’s work first hand. By then, his architecture was fully expressed and his best works were already produced – Center Pompidou in Paris (with Richard Rogers, 1971-77); The Menil Collection in Houston (1982-86); San Nicola Football Stadium in Bari, Italy (1987-90); Kansai International Airport Terminal (1988-94) in Osaka, Japan; Beyeler Foundation Museum in Riehen, Switzerland (1991-97); and Jean-Marie Tjibaou Cultural Center in Noumea, New Caledonia (1991-98). Piano’s architecture is well-balanced. It is daring and radical, yet, it is always impeccably cited, meticulously crafted, and beautifully integrated with landscape and natural light. In addition to performing whatever functions at hand, his buildings are often lifted off the ground to admit plenty of sunlight and create public gathering spaces in front of them; their graceful lines and refined details evoke beautiful ships or giant musical instruments.

The following is an excerpt from our 1.5-hour conversation at the busy Renzo Piano Building Workshop in New York, right across from Piano’s 2015 Whitney Museum that may not be as inventive as his earlier projects, but still, this battleship of a building pulls you in again and again to discover something new with every visit, both within and in the surrounding city from its open decks and connecting stairs. We discussed some of the architect’s current and earlier projects, while he reflected on beauty, intuition, imagination, and, of course, the necessity of a protest.

Vladimir Belogolovsky: You studied architecture at the Milan Polytechnic University where you did a dissertation on fabrication and modular lightweight structures. Could you touch on why you became interested in that kind of architecture?

Renzo Piano: I grew up in the family of builders and I always wanted to be a builder. I only discovered architecture as a student; I could not study it in my hometown, Genoa, and I really liked the idea of running away from home to study elsewhere. So, I went to Milan. But it was always about the process of building and building at that time was about modular construction to achieve an economic way of building. Also, it was a nice way to grabble something solid. Modularity is about an order. Life is always about order and disorder. Even a musician needs a pentagram to write notes. So, it was about anchoring my ideas on what is rational and clear. And, don’t forget, it was a period of student unrests, so we, students were concerned about ethics, economy, making buildings for people, and about the size of things – in meters, centimeters, and millimeters.

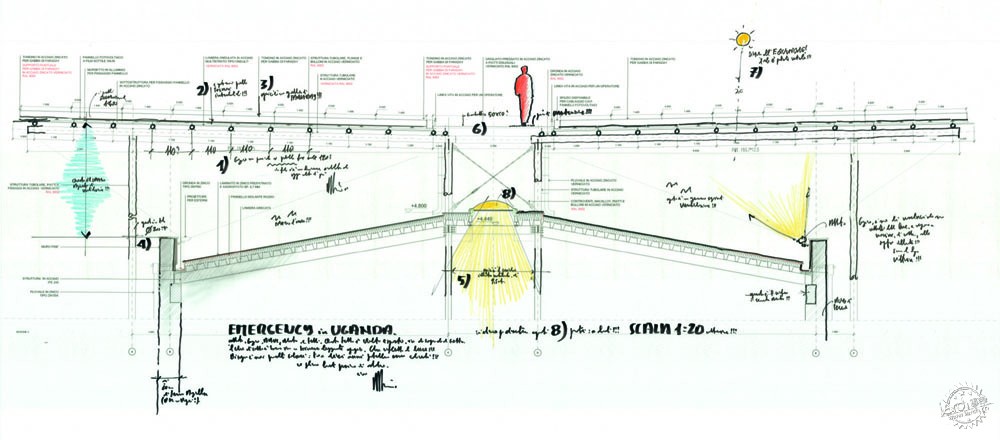

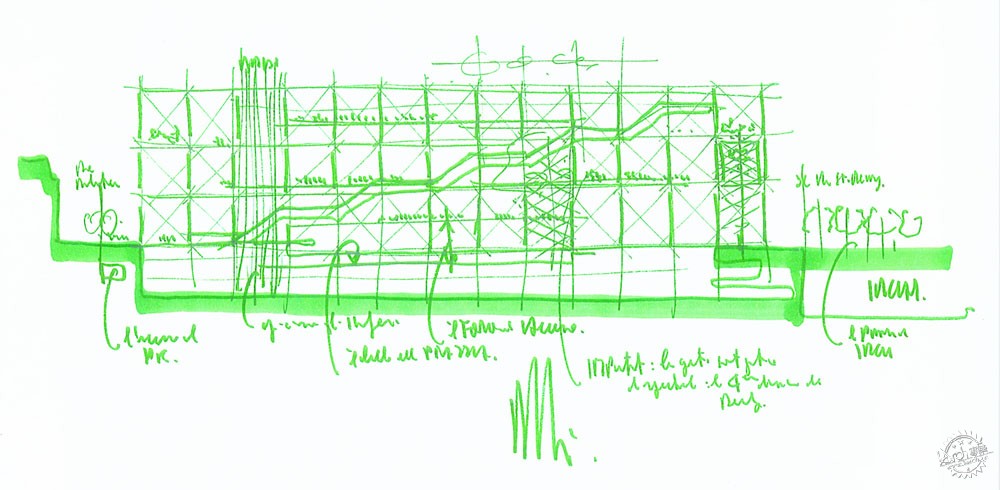

乌干达恩德培儿童急救中心|Emergency Children Surgery Center, Entebbe, Uganda

VB:你的父亲所建造的建筑,其中的精准性、轻质性、坚固性、耐久性,是否经得起考验呢?

RP:当然了。这是关于建筑的本身,关于作品的基本几何形态,而对我而言,作品是关于纪念诸如Jean Prouvé等人,他们发明的体系能够让建筑服务于大众。这就是个道德理念,也是模块化大规模工业生产,这些轻质结构象征着自由。

VB:因此你的职业生涯中,你不断地尝试大规模生产、模块化、轻质结构是吗?

RP:我比较喜欢那种拼贴而成且有特征的作品,当然现在这不太可能实现,我们可以通过不同的片段来进行拼贴,但是应用机器也许能够快速的实现。

VB: Was this precision and lightness and protest against the solidity and durability of the kind of projects that your father was building?

RP: It was, of course. But basically, it was about the building itself. About geometry, which is based on production. And for me, production was about admiring people like Jean Prouvé who was concerned about inventing a system that would allow building architecture for everybody. It was a moral idea. It was about mass production and industrialization; these light structures were seen as signs of freedom.

VB: And you stayed on this course of experimenting with mass production, modularity, light structures for your entire career.

RP: I like the kind of architecture that is made piece by piece, with many identical pieces. Of course, now this is no longer true, and we can as effectively build buildings out of pieces that are all different. The machines now make it possible.

乌干达恩德培儿童急救中心|Emergency Children Surgery Center, Entebbe, Uganda

乌干达恩德培儿童急救中心|Emergency Children Surgery Center, Entebbe, Uganda

乌干达恩德培儿童急救中心|Emergency Children Surgery Center, Entebbe, Uganda

VB:你的作品蓬皮杜艺术中心,就是内外翻转上下颠倒?

RP:是的。这关乎开放性与灵活性。我们希望让这座建筑实现开放化与真正的转变。

VB:它十分大胆,极具挑战新,那么相比起蓬皮杜艺术中心,每个项目都是新项目吗?这太具有革命性了。

RP:那我也不会这么想。例如,我们刚刚完成的乌干达小型医院,这就是比蓬皮杜艺术中心更有挑战性的建筑,因为我们设计了很厚的墙体,这样能够吸收太阳能量,这座建筑很美观,对于医院来说这很重要。另外,旧金山的加州科学中心也很具有变革性,我们应用了可持续技术,它也成为了城市第一座LEED白金认证建筑。其实我并不想让每座建筑都变成蓬皮杜艺术中心。能够让我进步的不是我已经完成的项目,而是我要做的项目。我非常幸运在当下的时间能够接受到这么多的挑战,这象征着某个时代,是个变化飞速的时代。那座大楼在1968年5月学生抗议之后几年才得以建成。甚至有的人说我们的作品是当年那次抗议的唯一见证者。

VB: Your Pompidou Center, the Beaubourg, turned everything upside down and inside out.

RP: Yes, of course. It was all about openness and flexibility. We dreamed about making that building truly public and transformative.

VB: And it remains to be the most daring and provocative, and isn’t it true that with every new project you are compared to the Pompidou? It was such a revolution!

RP: I don’t think about it this way. For example, right now, we are finishing a small pediatric surgery hospital in Uganda and I believe it will be even more revolutionary building than the Pompidou because we are building very thick walls out of earth, it will capture the energy of the sun, and it will be a very beautiful building, which is very important for a hospital. Our California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco was revolutionary because of the use of sustainable technologies; it became the first public LEED Platinum building in this country. You know, I don’t think about the Beaubourg. What keeps me going is not what I have done but what I will still do. We were lucky to be challenged with the right project at the right time. It symbolized that time, the time of great change. Don’t forget that the building was built only a few years after the student riots of May 1968. And in fact, someone said that our building may be the only visible proof of May 1968.

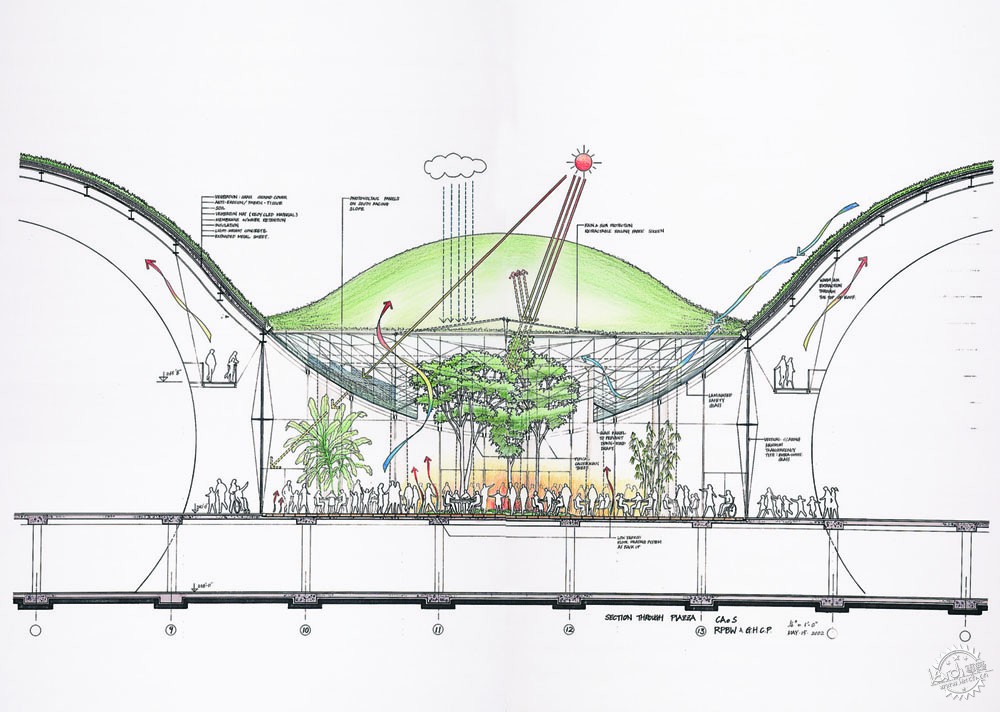

加利福尼亚州加州科学博物馆|California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco, USA, 2000-08

加利福尼亚州加州科学博物馆|California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco, USA, 2000-08

加利福尼亚州加州科学博物馆|California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco, USA, 2000-08

VB:这是一座具有革命精神的建筑,同时它也具有革新性,在今天也许无法建造这样的作品。

RP:是的。举例来说这不是在巴黎。我并不了解他们是否理解自己获得了什么东西。每次有人问我们问题,我们都会说,“我不了解你的意思。”嗯,我不理解(笑)。我相信新事物在不断地发展。你只需要某个特别的时刻,在幸运与好奇的陪伴下,一切都有可能发生,当然你也需要一些冒险。如果你只是做一些你已经知道的事,那么你就得不到新的东西。在建筑界,变化是必需品。我们设计作品并不只是让它看起来不一样,我们希望它代表了时代的变迁。

VB:你曾经说过,“作为意大利人,我很感激传统建筑。但是同样地,我也讨厌传统,因为它会让你止步不前。”你能说说建筑创新的重要性吗?这对你意味着什么?

RP:当然了,这不仅仅针对意大利。我说的是那些有着伟大历史、传统、记忆的场所。因为如果你没有在内心找到足够的能量,那么你就会完全被牵着鼻子走。我第一次离开家去米兰之前,先是去了佛罗伦萨,然后我开始学习,在那里呆了2年之后,我说,“天哪,我来这里干嘛?这里这么小,但是这么美丽。”(笑)我在这里干嘛?我喜欢美丽的东西,但是不久之后我就习惯了,然后呢?在20岁或者25岁的时候,我就需要有自己的想法,自己的好奇心,自己的想象力。这是人类的天性,我们必须要有自己的东西,这对于作家、科学家、音乐家来说都一样。

VB: It is a revolutionary building and it remains to be revolutionary. You may not be able to build something like this today.

RP: You are right. Not in Paris, for sure. And to be honest, I don’t think they really understood what they were getting. Every time we were asked a question we would say, “Je ne comprends pas.” I don’t Understand. [Laughs.] Well, I am sure new things can still happen. You just need a special moment. With some luck and curiosity, it can happen. You also need risk-taking. If you only draw what you know you are going nowhere. In architecture, change is a must. We didn’t design Beaubourg simply to make something different, visually it was an expressive proof of the changing times.

VB: You said, “Especially as an Italian, I am grateful to building tradition. But, at the same time, I hate tradition because it may paralyze you.” Could you talk about the need for invention in architecture? What is it for you – an invention?

RP: Of course, it is not only true for Italians. But I was talking about places with great history, traditions, and memories. Because if you don’t find rebellion and energy within you then you can become totally paralyzed by just admiring what’s already around you. When I first run away from home, before going to Milan I went to Florence where I started my studies. But after two years there I said, “My God, what am I doing here? It is too small, too beautiful.” [Laughs.] What can I do here? I love beauty, of course, but after a while, you get accustomed to it. And then what? When you are twenty years old or twenty-five years old you need to find your own freedom, your own curiosity, your own imagination. This is part of our nature. We must look for our own invention. And this is true for writers, scientists, musicians, for everybody.

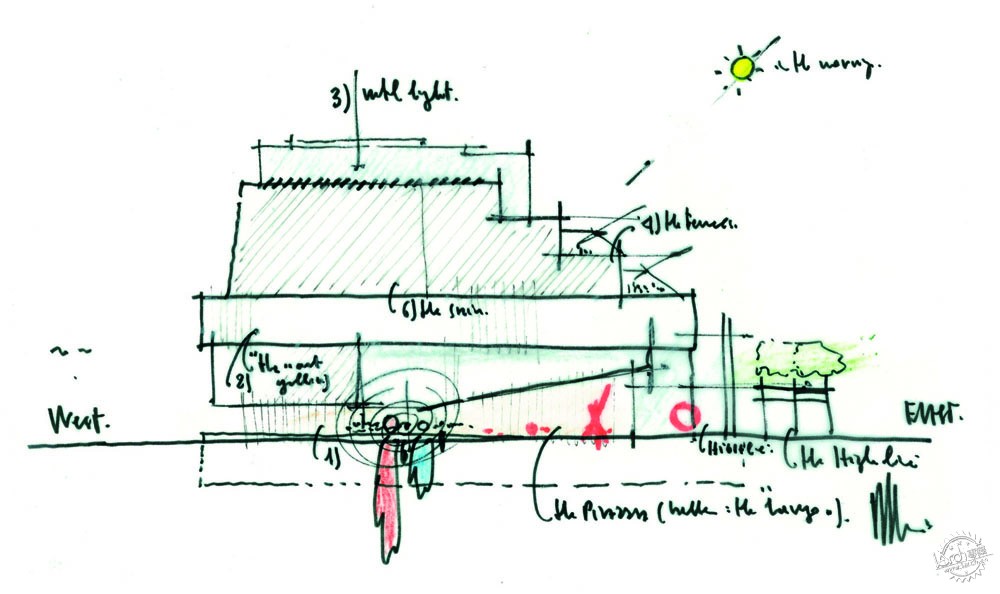

碎片大厦|The Shard, London_2000-12

碎片大厦|The Shard, London_2000-12

碎片大厦|The Shard, London_2000-12

VB:你能不能详细说一下你的话,你说过,“理性不会歌唱,但是直觉会。”

RP:好想法并不来源于理性,它就是个直觉的过程。你懂的,学习就是理性,但是直觉就像果酱。你不能吃太多果酱,你得学习制作的过程。因此,你同时需要理性与直觉。

VB:“作为建筑师,你需要了解施工、工艺,然后把它们结合起来,但是这还是远远不够。”

RP:是的,作为一名建筑师,你需要成为一名工人。钢琴家必须知道怎么弹钢琴,画家必须知道怎么画画。但是这还是不够,因为工艺、技术、语用,只是项目中很小的一部分内容。你要学习表达你的想法,建筑是对需求的构思,也需要满足人们的想法与灵感,甚至是梦想,这就是建筑与艺术的结合。建筑是对这些内容的表达。建筑是让人们能够相遇,是为了整个环境。你明白的,建造公共建筑时,这里就是人们的共同生活单元,博物馆、图书馆、学校、法院、医院、教堂,人们会聚集在这里,他们享受艺术、知识、教育、文明,甚至是美学。建筑实用吗?是的,但它也很艺术,也很社会。

VB: I would like you to elaborate on a few of your quotes. You said, “Rationality doesn’t sing; intuition does.”

RP: Good ideas don’t come from anything rational, they come through an intuitive process. You know, bred is like rationality and marmalade is like intuition. You can’t have too much marmalade; you need to put it on bred. So, you need both – rationality and intuition to pursue your curiosity.

VB: “Being an architect, you need to know how to build, craft, and put things together. But it is not enough.”

RP: It is true. Of course, as an architect, you need to be a good builder. A pianist must know how to play the piano and what’s the good of a painter who doesn’t know how to paint? But then it is not enough because nothing is ever about just the craft, technique, and pragmatics. You must express the desire. Architecture is the response to the need for protection but also to people’s desires, passions, inspirations, and dreams. This is where architecture and art come together. Architecture must be an expression of all of these things. And architecture is for people to meet; it is for the community. You know, when you make a public building it becomes a little miracle of civic life. Museums, libraries, schools, courthouses, hospitals, churches, celebrate the art of staying together. They celebrate art, knowledge, education, civility, and beauty. So, is architecture practical? Yes. But it is also artistic and social.

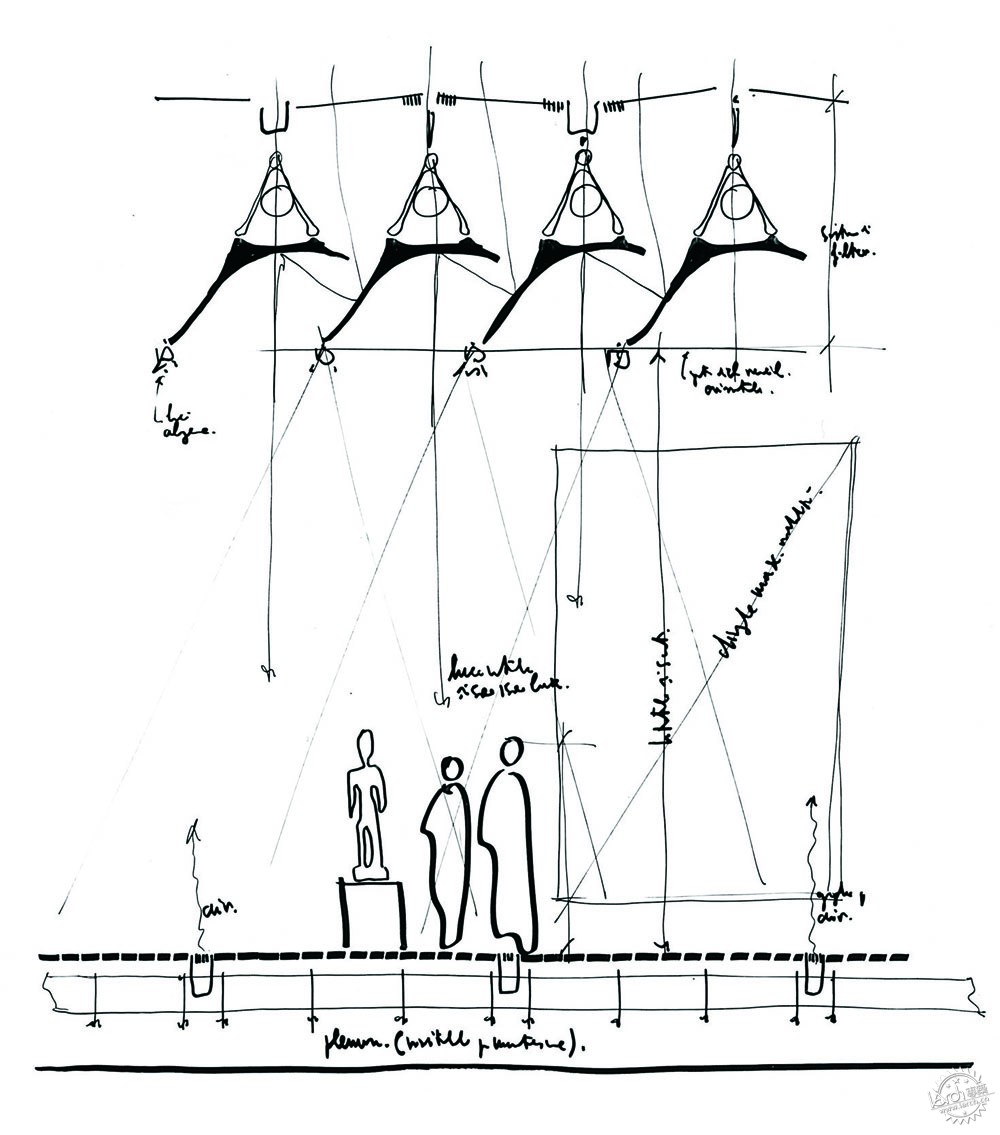

蓬皮杜艺术中心|Center Pompidou

蓬皮杜艺术中心|Center Pompidou

VB:“有时,建筑关乎抗争。”你还说过,“你必须叛逆,做自己。”

RP:你必须做自己。在某个年龄,你意识到在很小的时候就已经决定了自己的发展方向。当你8岁或者10岁时,你就已经有了一定的记忆。你成长于某个大环境之中,能感受到那里的天空与世界,对外来说,这就是关乎自己与海洋的关系。做自己并不自私,而是找到内心的自己。对我而言,Beaubourg区的蓬皮杜艺术中心是热那亚港口的一艘船。当然,在巴黎中心,它有些无厘头,但是这来源于我的潜意识。

VB:那惠特尼博物馆是热那亚港口的另一艘船吗?

RP:是的,但是这不是个开端,现在,我可能要建造一艘像船一样的建筑了。这有些愚蠢,首先,你得有建筑。当开始设计惠特尼博物馆到时候,我想要有广场,但是空间不够,因此只能把建筑抬高,倾斜下部,然后让阳光进来。做完这些之后,我发现这看起来就像是一艘船。但是这不是最开始的想法,否则你会一直被这个想法所引导,这其实挺危险的。

VB: “Sometimes architecture is about a protest.” And you added, “You have to be rebellious, you have to be yourself.”

RP: You have to be yourself; this is true. You know, at a certain age you realize that you are what you started to be when you were ten or even younger. When you are just eight, nine, ten years old you already have certain storage in your memory, under your skin. You grow up with certain desires within your surroundings – the sky, the line of horizon… For me, it was about my relationship with the sea and what is beyond it… Being yourself is not about being selfish, it is about discovering who you are. You know, for me, Beaubourg is a ship in Genoa harbor! Of course, it is in the middle of Paris, so it is totally absurd, but this is how I see it subconsciously.

VB: Is the Whitney here another ship in Genoa harbor?

RP: It is, but it is not how you start – OK, now, I am going to make a building that looks like a ship. This is stupid and very banal. First, you must make a building. When I started designing the Whitney I wanted to make a piazza. But there is no space for that, so you lift the building up, you angle the bottom for the sunlight to come in. You do all these steps and then you look, and you think, “Hm… it looks like a ship in the dock.” But that’s not how you start because otherwise you are driven by metaphors. And metaphors can be dangerous.

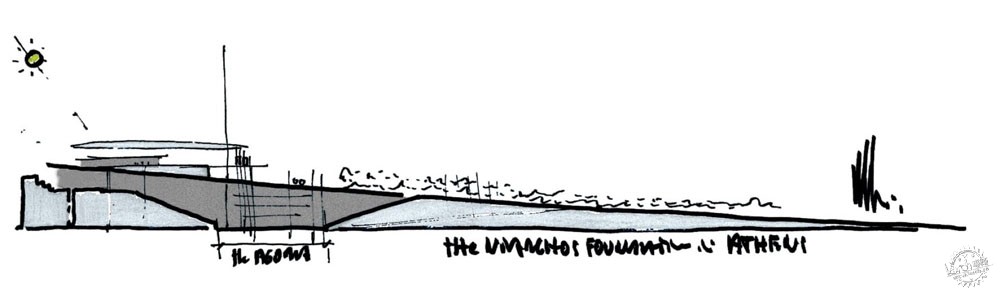

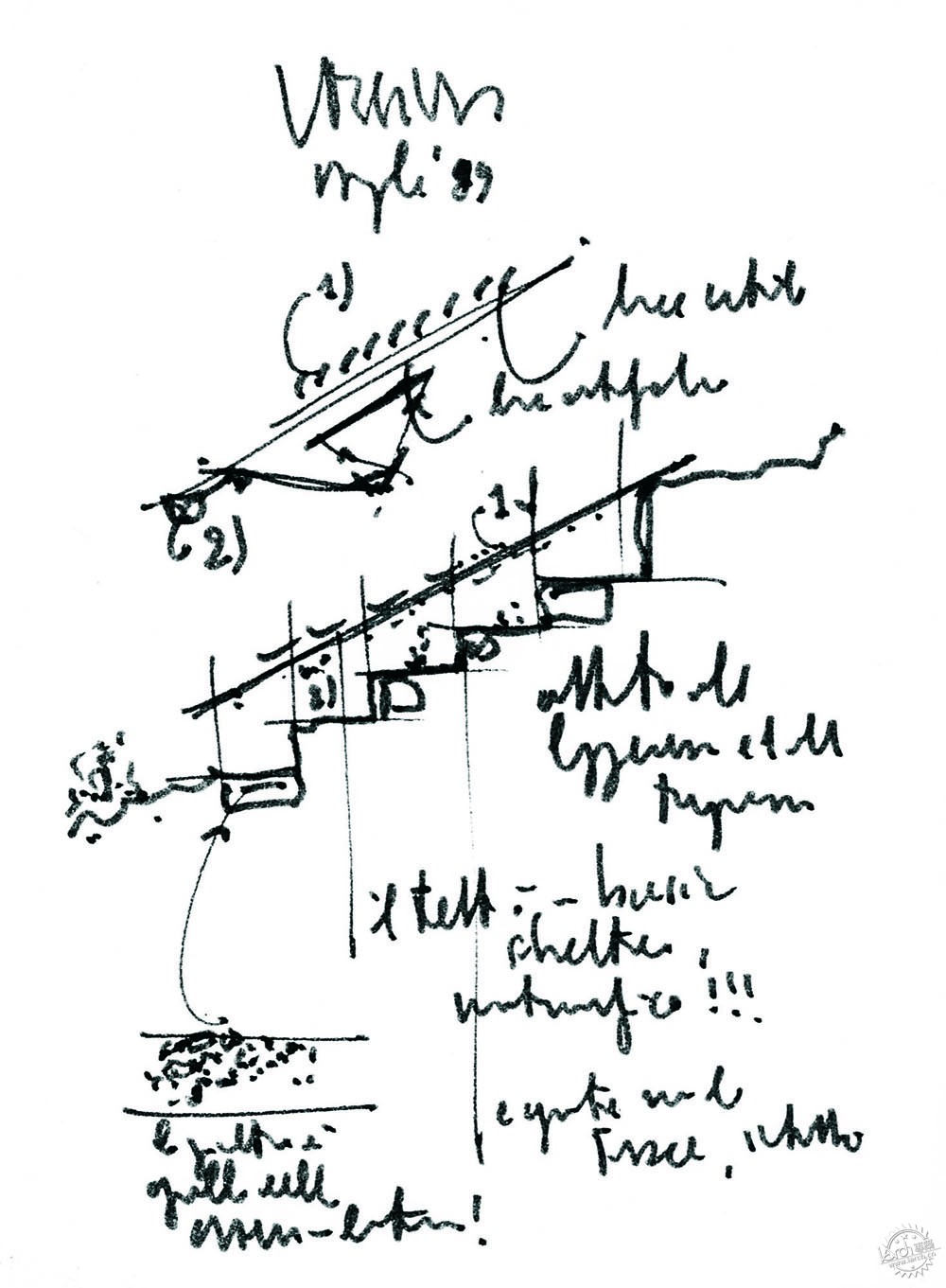

希腊Stavros Niarchos 基金会文化中心 |Stavros Niarchos Cultural Centre_2008-16_Athens, Greece

VB:即使这样,隐喻的概念在你的作品中还是十分明显,你说过,“船只漂浮着。”你还说过,“建筑能飞翔。”你知道Wolf Prix著名的一句话吗,他说:“我希望我的建筑能像云朵一样具有可塑性。”

RP:是的,这会更诗意一些。我的想法比较接地气,也比较个性化。我成长于港口,每天看着船只来来回回。其实这是个无意识的想法。我同意Prix的观点,但是我在设计之初并没有这么想,比如你看大阪关西机场,它看起来就像一架滑翔机,但是一开始并不是这样的。我们设计这座建筑时,只是希望它看起来轻盈一些,因为它位于地震带。我们并不会从具体的图像入手,因为这些都是后期出现的东西。

VB:你说过,“建筑最重要的是寻找美感。”你多次提到过美学,但是许多建筑师并不喜欢谈论美学。

RP:因为建筑师会比较担心,美学说多了自己会被误会是肤浅,毕竟这听起来很时髦。但是其实这非常深刻,甚至不可或缺。美学不只是眼睛看到的东西,而是发自内心的东西,就像一座冰山。我们会说一个人很美的时候,实际的意思是这个人很善良,内心很美好。在许多欧洲语言中,“美”这个词与“好”不可分割。美应该是我们的目标,也建筑师应该重视的。你看建筑的天窗,阳光能从这里进来,这就是微妙地捕捉美丽的事务的方式。

VB: Metaphors are quite important in your work, nevertheless. For example, you said, “Ships don’t touch the ground, they float.” You said, “Buildings can fly.” Do you know the famous phrase by Wolf Prix who expressed a similar desire by saying, “I want my buildings to change like clouds?”

RP: Well, that’s more poetic. My idea is more grounded and personal. I grew up watching ships in the harbor. This is all very unconscious for me. I agree with Prix, but I never think about it before I start designing. If you look at our Kansai Airport in Osaka. Yes, it looks like a glider, but no one talked about the glider in the beginning. We designed that building to be light and not only because it is on water but also because it is in a seismic area. We never start with the image, it comes later in the process.

VB: You said, “More than anything architecture is a search for beauty.” You know, you mentioned beauty a number of times in this conversation, but architects don’t like talking about beauty.

RP: Because architects are afraid that beauty may be mistaken for fashion, frivolity, decoration, superficiality. But it is actually very profound, deep, and even essential. Beauty is not just about what we see, but what is inside or underneath, like in the case of an iceberg. And when we say, “A person is beautiful.” That’s what we mean – a person has a good heart, character, a beautiful mind. The idea can be beautiful. In most European languages the word “beauty” is inseparable from the word “good.” Beauty should be our aspiration and architects should be more mindful of it. Look at some of our buildings’ skylights – they are capturing sunlight but more than that; they are capturing beauty in a very subtle way.

希腊Stavros Niarchos 基金会文化中心 |Stavros Niarchos Cultural Centre_2008-16_Athens, Greece

希腊Stavros Niarchos 基金会文化中心|Stavros Niarchos Cultural Centre_2008-16_Athens, Greece

VB:但是美并不是客观存在的东西,你在休斯顿的作品梅尼尔私人博物馆就被公认为很美,但是蓬皮杜艺术中心还欠缺一些。一些人会根据建筑的功能而认可其美学基础,也有一些人则完全不理解,这其中也有很大的分歧是吗?

RP:因为这不是一座需要取悦每个人的作品,蓬皮杜艺术中心直接且开放,它的美学来源于功能,因此从这个角度来说,这是一个重磅炸弹。但是这些的目的都是让艺术更加的亲民。后来当我看到人们在这座建筑里,或者是在这里聚集的时候,我会感觉,这才是真正的美学,美学与快乐并不是一个东西。一位好建筑师就像是一位好医生,他会告诉病人病情的具体情况,这是一件正确的事情。当你在设计建筑时,并不是你想要设计不同的东西,而是这个世界就各不相同,而你的作品也因此不同。在1989年,柏林墙倒塌了,现在我们面对的是一个不同的世界,随时都有新故事,我们要思考、要反思、要创新、要评论,我们设计建筑并不是为了取悦谁,设计方式不同,呈现的效果也不同,对周围环境的影响也不同,创新与改变没那么容易让人接受。当然如果我为了变化而变化,那呈现的效果也不好。蓬皮杜艺术中心刚刚投入使用时,批评的声音很大,人们花了很多年才逐渐接受它,现在这里是巴黎最受欢迎的地方。当然,还是有一些人不喜欢它。当我第一次公开惠特尼博物馆的设计方案时,人们也很抗拒,但是经过一段时间之后,抗拒的人越来越少,后来人们也都接受它了,时间问题而已。

VB:在1998年普利兹克建筑奖的获奖感言中,你说过,“创新意味着抓住黑暗,放弃参考,面对未知的世界。”你也说过,“过去是安全的场所,这也是持续的诱惑。但是,未来是我们向往的方向。”你能说说关于进步和探索吗?

RP:这对任何人来说都是事实,不只是针对建筑师。创意工作就像在黑暗中寻找光明,你必须足够有勇气去面对未知。安全的场所也存在,但那时候我们就不需要思考实验性作品,因为这是未来的概念,如果这样你就失去了你的特征,失去了你自己的特性。每个人都有自己的美学,这一点无法逃避。现在这个世界很脆弱,这说明我们无法像以前那样简单地完成一切任务。未来是我们唯一的道路,我们必须接受这一点。Jorge Luis Borges,想象来源与记忆与遗忘,我们幸好忘记了很多东西,因此我们必须不断向前。创意来源于传统与发明。

VB: Beauty, of course, is not objective and, while much of your buildings as The Menil Collection in Houston is accepted as universally beautiful, the Beaubourg is still not accepted as such, right? There is a strong division between those who see it as beautiful because of how it functions and those who don’t understand it at all.

RP: Because it is not the kind of building that wants to please everyone. The Beaubourg is beautiful in its roughness, its directness, openness. It is beautiful for what it did, for what it offered to people. So aesthetically speaking, the Beaubourg is a slam in the face. But it was all about making art accessible. And that’s beautiful. And now when I see how people use that building and how they gather around it, that’s beautiful. Beauty and pleasing are different things. A good architect is like a good doctor who doesn’t try to please a patient. A good doctor tells his patient the truth. It is about making the right thing. You know, when you make a building that’s different it is not because you just want to be different. No, it is because the reality is different, the world is different. Everything is changing all the time. The Berlin Wall fell in 1989; it is a different world now. Every time there is a new story to tell, to comment, to reflect on. We don’t build buildings to please the crowd. No, you build differently because you respond to the changes around you. Changes are never accepted easily by people, never. And if my architecture is about celebrating the changes, of course, it is not going to be accepted by everyone. Almost no one accepted the Beaubourg when it just opened. It took many years for people to like it. It is now one of the most beloved places in Paris. Of course, you are going to have some taxi drivers who hate it, but it is accepted now. When I first presented the new Whitney and when it was just opened there were doubts and questions, but over some time there were less and less of them and now it is loved by people. It takes time.

VB: In your 1998 Pritzker Prize acceptance speech you said, “Creating means grasping within the dark, abandoning points of reference, facing the unknown.” You said, “The past is a safe refuge. The past is a constant temptation. And yet, the future is the only place we have to go.” Could you touch on this idea of perpetual progress and exploration?

RP: Well, this is true for anyone, not just architects. Creative work is like looking in the dark. You need to be brave enough not to look for safe ground. It is fine to look for safe ground but then we are not talking about experimental architecture, which is about going forward. Then you are missing your role, which is to be yourself in your own time. Everyone must find his own beauty and you can’t run away from that. The key message of our century is that the world is fragile. This means we simply can’t build the way we used to. And in any case, the future is the only place we can go to. We must accept that challenge. Jorge Luis Borges said that imagination is made of memory and of oblivion. Thank God we forget things, so we have our imagination to move forward. Creativity is always a mix of tradition and invention.

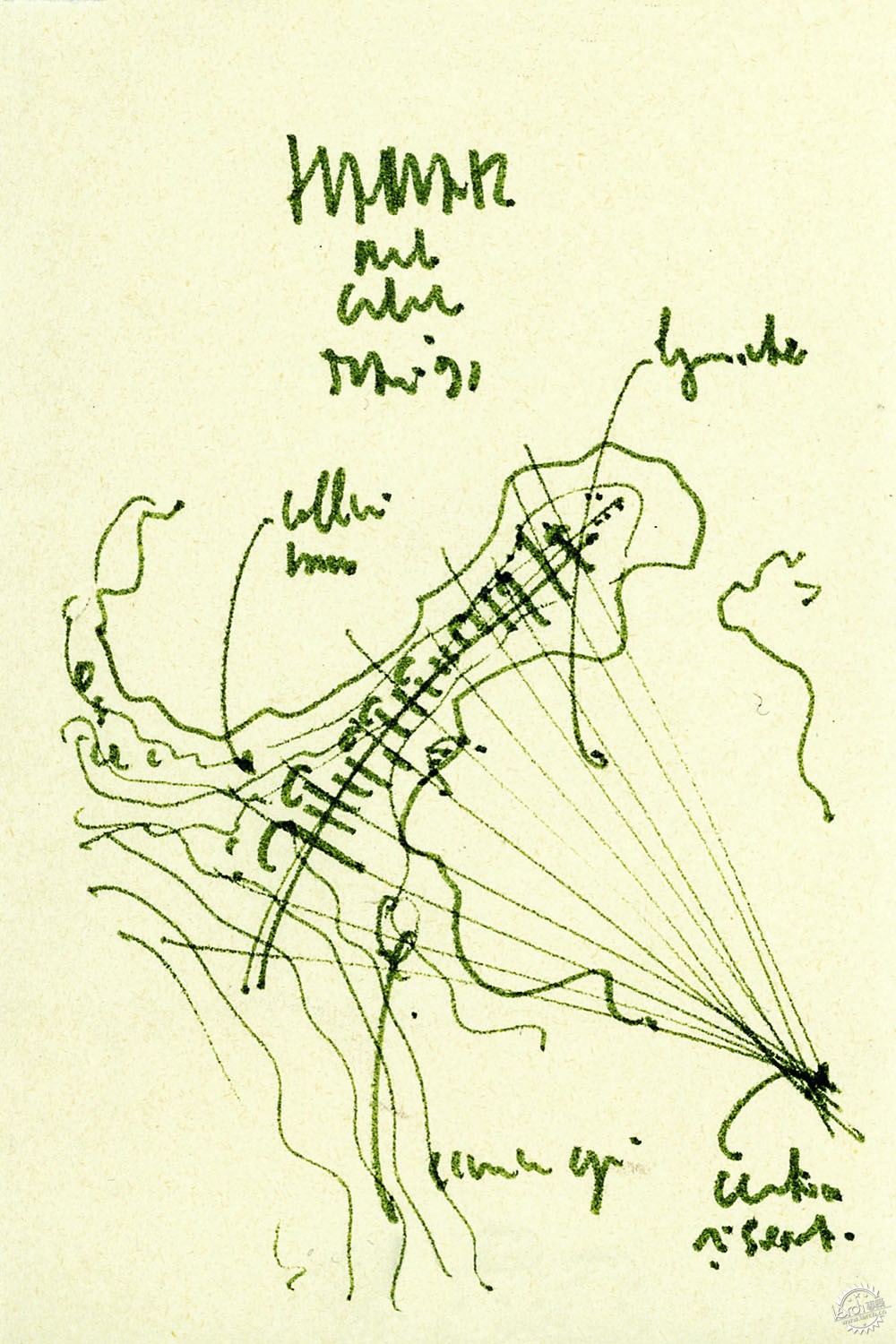

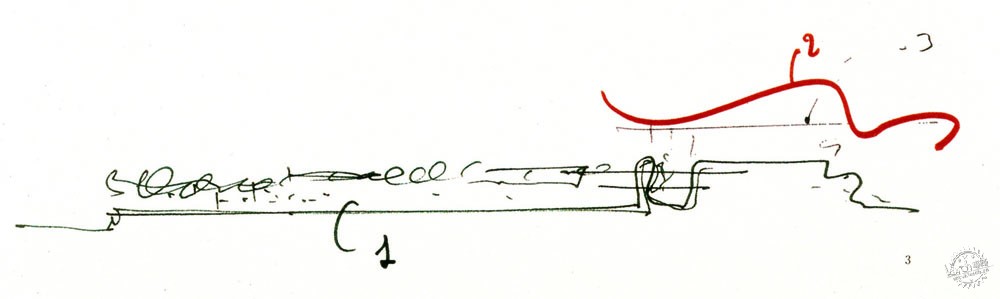

让·马里·吉巴乌文化中心|Jean-Marie Tjibaou Cultural Centre, 1991-98, Noumea, New Caledonia

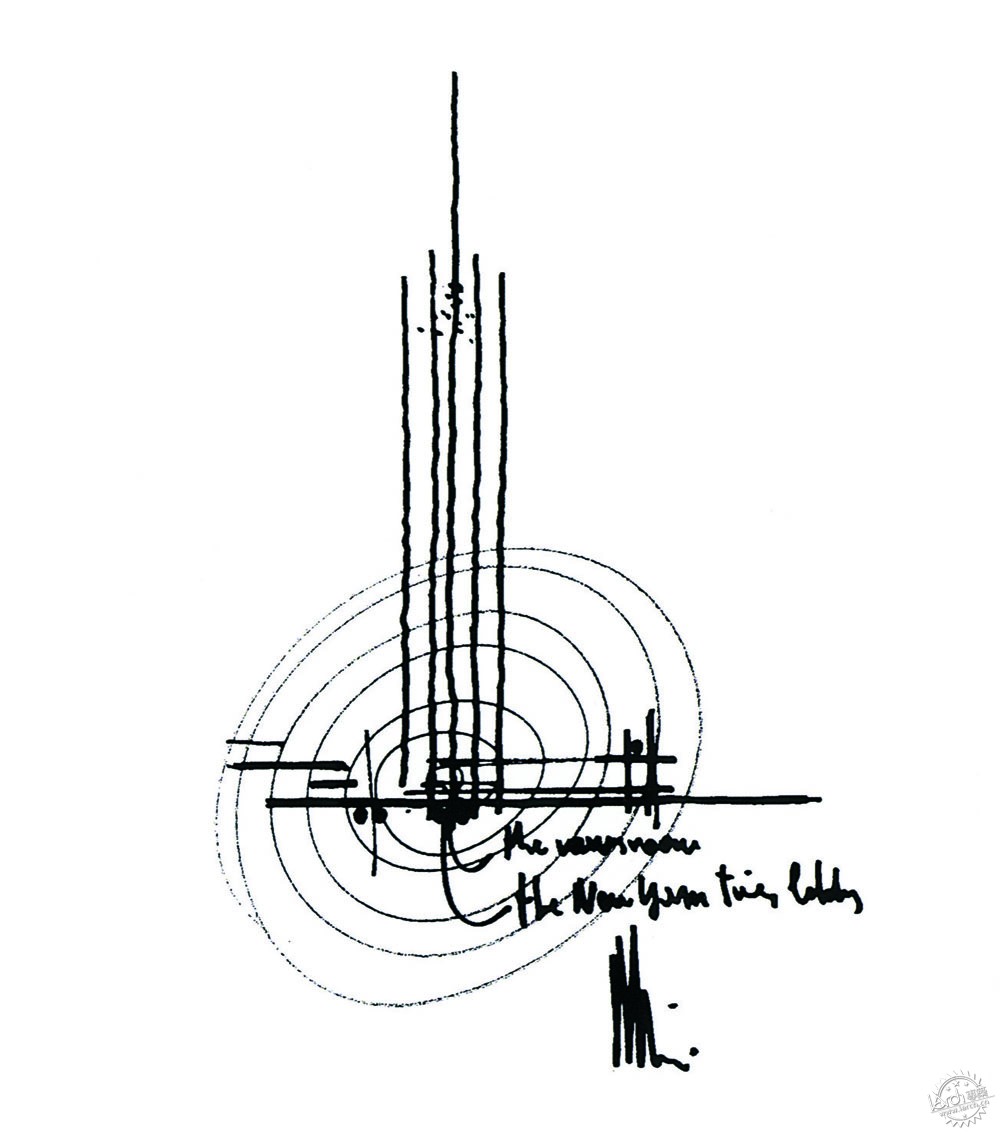

纽约惠特尼博物馆|Whithney Museum, New York

纽约惠特尼博物馆|Whithney Museum, New York

伦佐·皮亚诺建筑工作室|Renzo Piano Building Workshop_1989-91_Genoa, Italy

纽约时报大厦|New York Times Tower, New York

休斯敦梅尼尔收藏博物馆|The Menil Collection_1982-86, Houston, USA

关西国际机场|Kansai International Airport, 1988-94, Osaka, Japan

|

|