维特拉会议馆,德国|Vitra Conference Pavilion, Weil am Rhein / Germany. Image © Vitra, by Richard Bryant

When Sunlight Meets Tadao Ando’s Concrete

由专筑网李韧,王雪纯编译

普利兹克建筑奖获得者安藤忠雄曾经说过,如果他的作品中必须要有某个统一的元素,那就是光。安藤对于光影的应用让人们在建筑中充分感受到时空的变换,有时候是墙体上静态的光影,有时候是水池中动态的反射。安藤将日本传统建筑风格与现代主义特征相结合,强调了传统的地域主义。他非常关注项目地点的环境与背景,同时注重表达自身的特点与情感,诸如光之教堂、小筱邸住宅、水御堂等著名作品很好地将设计概念、现代空间、材质、光结合在一起。另外,遍布阳光的日式墙体也可以和其他的文化背景相结合,这就好像罗马万神庙的顶部,一束阳光进入空间的内部,如同巴黎François Pinault当代艺术基金会那样,安藤杰出的想象力构思了空间的明暗序列。

If there is any consistent factor in his work, says Pritzker-winning architect Tadao Ando, then it is the pursuit of light. Ando’s complex choreography of light fascinates most when the viewer experiences the sensitive transitions within his architecture. Sometimes walls wait calmly for the moment to reveal striking shadow patterns, and other times water reflections animate unobtrusively solid surfaces. His combination of traditional Japanese architecture with a vocabulary of modernism has contributed greatly to critical regionalism. While he is concerned with individual solutions that have a respect for local sites and contexts Ando’s famous buildings – such as the Church of the Light, Koshino House or the Water Temple – link the notion of regional identity with a modern imagining of space, material and light. Shoji walls with diffuse light are reinterpreted in the context of another culture, for instance, filtered through the lens of Rome’s ancient Pantheon, where daylight floods through an oculus. Ando’s masterly imagination culminates in planning spatial sequences of light and dark like he envisioned for the Fondation d’Art Contemporain François Pinault in Paris.

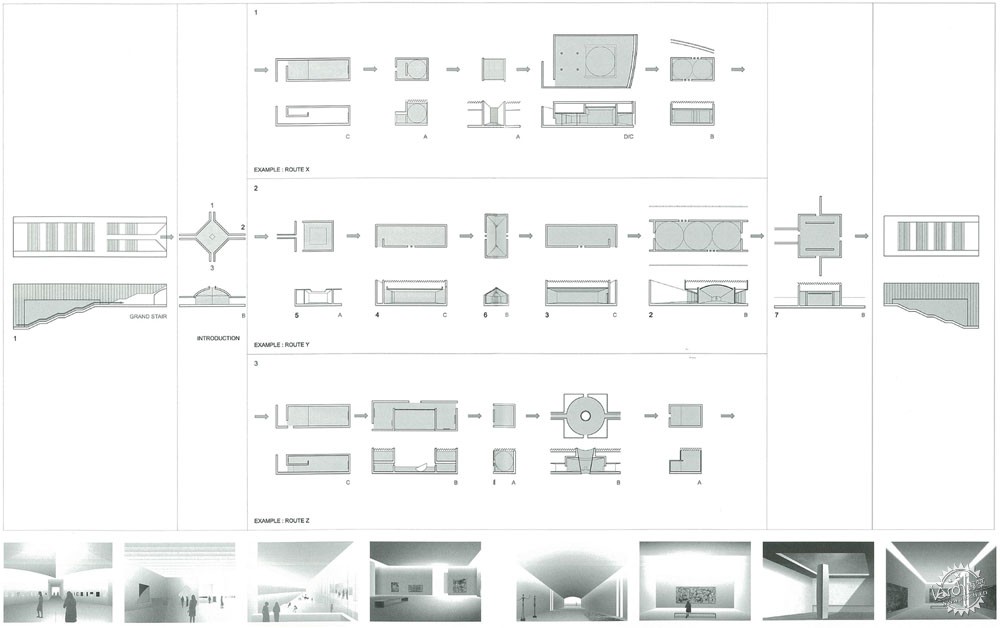

弗朗索瓦·皮诺特当代艺术基金会,法国巴黎|Illustration of daylight openings in ground plan, section and perspectives for the Fondation d’Art Contemporain François Pinault, Paris (France)/2001. Image © a+u (Ando 2002)

二战后的日本不允许公民去国外旅行的禁令于1964年才宣布废止,当时24岁的安藤忠雄才终于能够乘坐火车去欧洲旅行。在罗马万神庙的感受给他留下了深刻的印象,这也让他决定继续建筑生涯。Jun’ichirō Tanizaki在其著作《光影的赞美(In Praise of Shadows)》中称赞了光影的微妙,万神庙中沿着穹顶分布的梁和楼板则显得有些排外。安藤热爱日式门窗与露台,其内心有着对国家的深深情感。相比之下,万神庙顶部中央的开口呈现出魔幻般的形态,让光线照射进来,因此整座建筑光线充足,但是却有眩光。

After the Second World War, Japanese citizens were prohibited from foreign tourism but the ban was lifted in 1964 enabling a 24-year-old Ando to travel to Europe the following year on the Trans-Siberian Railway. His visit to Rome, especially his experience of the Pantheon, made an intense impression on him and confirmed his decision to continue his career as an architect. Coming from a country where Jun’ichirō Tanizaki had wonderfully lauded the tradition of appreciating shadow and subtlety in his book In Praise of Shadows, the harsh beam in the Pantheon moving along the dome and floor must have appeared completely foreign. Indulging in the so glow of shoji, the famous sliding paper doors, and the softened daylight through garden and veranda had defined the gentle sensibility of his home country. In contrast, the one clear, central cut-out in the Pantheon ceiling represents a dramatic gesture which strives for maximum brightness. The building is flooded with light, and glare is unavoidable.

光之教堂,日本大阪|Church of the Light, Osaka / Japan. Image © Naoya Fujii

将传统几何形态直接借鉴在自己的作品之中并不是明智之举,但是引入这种戏剧化的空间氛围的方式影响了安藤从博物馆到寺庙的众多项目。在日本大阪茨木的光之教堂设计建造于1989年,建筑没有像万神庙那样直面天空,但是它仍然很好地表达了安藤忠雄对于光影的热爱,这种表达形式在日式建筑中很少见。安腾在墙体上构思了十字架凹槽,在一开始,他原本想在开口中应用玻璃,这样看起来就有点万神庙的感觉了,但是因为此地寒冷的冬季,所以这个想法无法实现。

Transferring the ancient geometry directly to his own architecture may have been out of the question, but the idea of introducing a more dramatic atmosphere has influenced numerous projects from museums to temples. The renowned Church of the Light in Ibaraki, Osaka (1989), might not directly reach out to the sky like the Pantheon, but it manifests Ando’s desire to confront light and shadow in a strong way – very uncommon for traditional Japanese architecture. He achieves a comparable divergence with the cross-shaped slots at the back wall of the sanctuary. Originally, he would have preferred to leave the glass out of the opening – which would have intensified the link to the Pantheon – but climatic conditions in winter made this unacceptable to the church.

头大佛,日本,札幌|Screenshot of video of Hill of the Buddha at the Makomanai Takino Cemetery, Sapporo / Japan. Image © Hokkaido Fan Magazine

在2017年,安藤忠雄在日本札幌 Makomanai Takino 墓地中设计了一座巨大的、由薰衣草覆盖着的寺庙,这个空间就大有万神庙的形象了,当人们逐渐走进时,大型佛像变逐渐出现,整个空间充斥着各式明暗、光影的组合效果。蓝天映衬着巨大的雕塑形成无尽的空间感。墙面、天花板、地板应用了冷灰色混凝土,这是安腾作品的明显特征,同样也是这一手法,使得他的作品与西方现代建筑中的白色方形体量有着显著的区别。

The prominent image of the Pantheon reappears later for the Hill of the Buddha at the Makomanai Takino Cemetery in Sapporo (2017). When approaching the end of the tunnel leading to the rotunda, the Oculus turns into an impressive halo for the head of Buddha, showing the skillful composition of various brightness levels, space and vistas. The blue sky encircles and transcends the massive white statue. The cool, grey concrete for walls, ceilings, and floors constructs an intense homogeneity in Ando’s architecture. Thanks to this consequent language he has achieved independence from the bright white cubes of modern Western architecture.

小筱邸住宅,日本|Koshino House, Ashiya-shi / Japan. Image © Kazunori Fujimoto

在墙体与天花板之间的缝隙立着安藤式墙体,在白天构成了具有韵律的光影节奏感。漫射着阳光的通道打破了混凝土表面,将垂直空间与水平空间分隔开,强调了空间的进深感,强烈光影的出现短暂却明晰,当阳光沿着墙体照射时,会产生清晰的投影。日本兵库县的小筱邸住宅则有着两种不同的效果,其一是沿着直线墙体,其二是沿着弧线墙体。投影的角度在墙上的光面构成了清晰的线条,强调了魔幻般的光照效果。在维特拉研究中心中,也有着类似的氛围,光线在直线与曲线墙体中环绕,投影表达着时间概念。

Ando’s elegant slits between wall and ceiling generate a poetic rhythm of light during the course of the day. Mainly restrained as a channel for diffuse daylight, they break the concrete surfaces and separate vertical from horizontal, intensifying the spatial depth. e moment of crescendo is short but intense. It emerges when the rays of sunlight run very close along the wall and produce a layer of striking shadows. The Koshino House in Ashiya (1984) features this effect in two variations, first along straight walls and later for the extension with a curved wall. Diagonal bands of shadow cut the fields of light grazing the walls and heighten the dramatic daylight gesture. The Vitra Conference Pavilion benefits from a similar atmosphere with its straight and curved walls, where the distinct shadows make the time tangible.

北海道水之教堂,日本|Church on the water, Hokkaido / Japan. Image © Ji Young Lee

在水之教堂里,窗户上的十字架缩短了人们与建筑的距离,由于阳光方向不同,十字架的投影会在地面上缓慢地移动,清楚地表达了太阳的运动轨迹,在日本神户4x4住宅中,也有类似的效果。安藤在美国的作品中,窗户的十字交叉主题变有了例外,因为其在这里的作品似乎受到了密斯的影响。芝加哥住宅、曼哈顿阁楼、纽约伊丽莎白152公寓都应用了有着竖向线条的玻璃,在阳光之下,地面上便有着清晰且平行的投影。

At the Church on the Water, the cross in the window overcomes the distance between the congregation and the cross on the water. Depending on the orientation, the cross traces the course of the sun with a shadow pattern moving quietly across the floor – also staged, for instance, for the tower at the 4x4 House in Kobe (2003). An exception to the cross theme in windows occurs in Ando’s projects in the US where Mies van der Rohe’s influence seems to become perceptible. The House in Chicago, the Penthouse in Manhattan from 1996, and the 152 Elizabeth apartment block in New York (2017) display windows as a glass membrane with thin vertical lines. Hence, parallel lines of shadow become visible on the floor.

沃斯堡现代艺术博物馆,美国|Modern Art Museum, Fort Worth / USA. Image © Todd Landry Photography

环绕水池排布的建筑已经成为了安藤忠雄建筑作品的重要设计元素,例如在日本京都光明寺中的方形水池就让建筑看起来更有活力,2002年沃思堡现代博物馆则强调了建筑的轻盈感,而2004年德国Langen基金会项目则表达了入口特征。在晚上,灯光从玻璃立面散射而出,室内的灯光似乎可以照亮水池。在白天,人们可以在三个悬臂式大屋面下观赏具有动态感的水面反射。

The concept of surrounding buildings with reflecting pools has turned into an important design element to Ando, contributing animation – for example at the Komyoji Temple in Saijo (2000) with its rectangular pool, at the Modern Art Museum, Fort Worth (2002), to enhance the lightness of the building, or at the Langen Foundation in Neuss, Germany (2004) for an impressive entrance gesture. At night, when the wall washed concrete behind the glass facade allows the buildings to glow from within, they seem to oat on the reflecting pond. During the daytime, visitors can enjoy dynamic water reflections on the underside of the three prominent cantilevered roofs in Fort Worth.

本福寺·水御堂,日本,淡路岛|Water Temple, Awaji Island / Japan. Image © Relan's Terraces

位于兵库县淡路岛的水御堂则完美地展示了光的韵律。在光滑混凝土的直线墙体与弧线墙体之中有着一个空腔,上方是开阔的天空,地面上是白色的石材,这是人们达到之后看到的第一个场景。然后人们会走向圆形的水潭,周边环境倒映在水中,水波柔和的映衬着天空。矩形的入口把人们引导向黑暗的空间里,在进入内部空间之前,人们会经过直线混凝土墙体,墙上倒映着微蓝的天空。红色木材屏风位于下侧,它们漫射着刺眼却清爽的日光。

在来到主要空间之前,人们会发现,光线并不是来自于头顶,而是来自于前侧,这把人们吸引向前方。一系列的空间就像是朝圣之旅的精炼,通过一条纯净的通道净化心灵,当人们再进入黑暗空间之后,则能感受到鲜血般的生命气息。

美国建筑学教授Henry Plummer认为这段历程充满了灵性:“在经过红色鲜血般的体验之后,人们经历黑暗、经历水域,回到地面,回到干燥的空气之中,这段历程激发了超出人们想象力的情感波动。”

本文最初发表于《照明》杂志的增刊中,标题为“混凝土的本质”。

“Light matters”是《光与空间》的专栏,作者为Thomas Schielke博士,作者生活于德国,痴迷于建筑照明,同时是照明公司ERCO的编辑。他发表了许多文章,合著有书籍《Light Perspectives》和《SuperLux》。

Located on Awaji Island, the Water Temple materializes the choreography of light in a perfect way. The arrival begins with a void between a straight and curved wall in smooth concrete with an open sky above. A texture of white gravel, which calmly lies on the ground with a new shadow pattern, creates the first bright scene. The journey leads to the round lotus pond, where an intriguing play of water reflections mirrors the sky with gentle waves. The rectangular entrance slit guides the eye downwards to darkness. The straight concrete walls reveal faint blue reflections from the sky before one enters the realm of diffuse red light. Vermilion wooden screens on the lower level turn the harsh, cool blue daylight into a warm diffused glow.

When reaching the main altar another alteration becomes apparent: the direction of light does not come anymore from above but from the front, drawing believers to the light and the sanctuary. This sequence of spaces condenses a pilgrimage within one temple – a purifying passage of whiteness, descent into darkness followed by awakening with bright red, like blood, signifying life.

US architecture professor Henry Plummer regards the spiritual passage leading back as an analogy to a birth: ‘To climb back out to the thin blue light of day after this deeply viscous red experience, up through the ground, out through the dark canal, through the uterine waters into dry air, is to arouse dazzling images which go far beyond our immediate memory.’

This article was originnaly published in an extended version in the Lighting Magazine under the title “The Nature of Concrete”.

Light matters, a column on light and space, is written by Dr. Thomas Schielke. Based in Germany, he is fascinated by architectural lighting and works as an editor for the lighting company ERCO. He has published numerous articles and co-authored the books “Light Perspectives” and “SuperLux”.

|

|