New City School, Frederikshavn / Arkitema Architects . Image Cortesía de Arkitema Architects

The Same People who Designed Prisons Also Designed Schools

由专筑网李韧,邢子编译

建筑师兼学术研究者Frank Locker认为,在建筑教育之中,人们重复着20世纪以来的各种机制,例如,不管学生的目的、兴趣、能力如何,老师总是教授一成不变的基础知识,并且这些知识毫无方向可言,Locker还认为,教育总是不断地复制,学校就如同是一座监狱,没有完整灵活的多功能教育空间。

Locker问道:“当你处在一个封闭的空间或走廊之中,如果没有得到许可,你甚至不能进入房间,亦或是你需要专门接收离开或进入的指示,对于这个空间你会是什么感受?”

According to architect and academic Frank Locker, in architectural education, we keep repeating the same formula from the 20th-century: teachers transmitting a rigid and basic knowledge that gives students, no matter their motivation, interests, or abilities, little to no direction. In this way, says Locker, we are replicating, literally, prisons, with no room for an integral, flexible, and versatile education.

"What do you think of when you're in a space with closed doors and a hallway where you can't enter without permission or a bell that tells you when you can enter and leave?" asks Locker.

"March of the 100 thousand umbrellas," protest in the context of the student marches of 2011 in Chile. Image © Rafael Edwards [Flickr CC]

当前,全球教育模式正受到各种质疑,并且也处在转变的契机之中,这已经不是新鲜事了。人们都了解,从法国大革命以及旧政权时期教育垄断的不断衰败中就能感受到这一点。

教育的改革随着时间的流逝而缓慢前进,但是这些进程的推进常常源于那些在现已废除教育体系中成长的人员,他们的成果往往只能为后代所感受。无论这些体系是处于何种性质,建筑都更应该偏向于反思,毕竟就建筑而言,这是国家和其他私人团体介于空间创造之上的真实意图。

The fact that global educational models are being questioned and put in various forms of transformation (or crisis) is nothing new. We've seen it since the French Revolution and the fall of the Ecclesiastical monopoly on education during the Old Regime.

Transformations in education happen slowly and with time. Curiously, they're typically ignited by those who grew up in now-defunct educational systems and their results will be seen by generations not even in existence. No matter the system, be it positive or negative, architecture tends to reflect upon rather than rebel against. Architecture is, after all, the visions of the state and other private entities made real beyond the allowed margins of spatial creativity.

Lucie Aubrac School / Laurens&Loustau Architectes. Image © Stéphane Chalmeau

因此,在信息时代,人们需要改变自己的教育模式,这样才能更好地适应社会特征。在一些案例中,诸如Mark Wigley指导的哥伦比亚GSAPP,其灵感便是来源于教育,因为这能解决许多未来的建筑问题。虽然拉丁美洲建筑研究仍然是满足社会流动的主要方式,但在许多非洲和亚洲国家之中,新兴建筑师仍然需要解决基础服务设施的缺乏问题。

So, in the era of information (a more accurate description than the era of knowledge), citizens are demanding changes in their educational models to better fit their societies and distinct idiosyncrasies. In our case, Columbia's GSAPP, directed by Mark Wigley, was inspired by education that would address the future questions of architecture. While studying architecture in Latin America is still a route to social mobility, in many developing parts of Africa and Asia, new architects are forced to deal with the lack of basic needs, like infrastructure and services.

监狱般的学习以及对老师的恐惧

Kirkmichael Primary School / Holmes Miller. Image © Andrew Lee

Locker在哥伦比亚评估波哥大教育部门,同时为建筑与施工公司提供咨询服务,主要针对学习全新模式的能力,这种能力能够解决现有的社会问题和文化变革。Locker有着丰富的建筑教育经验,他认为,人们正在不断地使用“监狱模式”,并且不断地通过20世纪的固化思维来限制学生和老师的兴趣和能力。

这位美国建筑师近期在哥伦比亚报纸《El Tiempo》接受采访时说,他对教育建筑的兴趣始于他在传统学校建筑中所接收到的作业,这也是他称之为“监狱模式”的原因,当被问到为什么今天的学校设计得像监狱时,他说:

“在美国,许多设计监狱的建筑师也在设计学校。当你看到一座大厅,周围大门紧闭,在没有得到允许你还不能走进房间,亦或是还专门有个闹铃提示你,什么时候该进去,什么时候该离开,什么时候上课,什么时候下课,在这样的环境中你有什么感受?”

School as a Prison and Fear of the Teacher

Locker was in Colombia assessing the Department of Education in Bogotá and advising architects and construction companies about a new model of study with the ability to address society's current social and cultural changes. With decided conviction and vast experience in architectural education, Locker says that we are limiting ourselves by continuing to use the "prison" model and by falling back on the old 20th-century formula of teachers passing on rigid and uninspiring knowledge to students with no concern for their different interests or abilities.

The American architect said in a recent interview with the Colombian newspaper El Tiempo that his interest in educational architecture began when he received assignments that were a far cry from the traditional school building: what he calls the "prison model." When asked why today's schools were designed like prisons, Locker responds:

“In the US, many of the same people who designed prisons also designed schools. What comes to mind when you see a long hall of closed doors, that you can't be in without permission, and a bell that tells you when to come in, when to leave, when class starts, when it ends? What does that look like to you?”

Saunalahti School / VERSTAS Architects. Image © Tuomas Uusheimo

孩子们在这种环境中的空间与时间都体现在教室中。Locker在接受哥伦比亚新闻《Semana》的另一次采访中说道:“在有的文化中,人们会觉得老师具有威严,而学校的布局方式也反应了这种教育理念。”那么回溯人们自己在学校中的生涯,回想一下桌椅排布的方式、老师的权威性,其实便很容易理解Locker的观点。

The spatial design and the time that children spend in this type of environment is reflected in the classrooms. In another interview with Colombian news outlet, Semana, Locker states that "in some cultures, it is expected that students fear the teacher, and school layouts reflect this educational philosophy." Looking back on our own school days, the layout of the desks, the unrefutable authority and knowledge of the teacher, it is easy to see Locker's point.

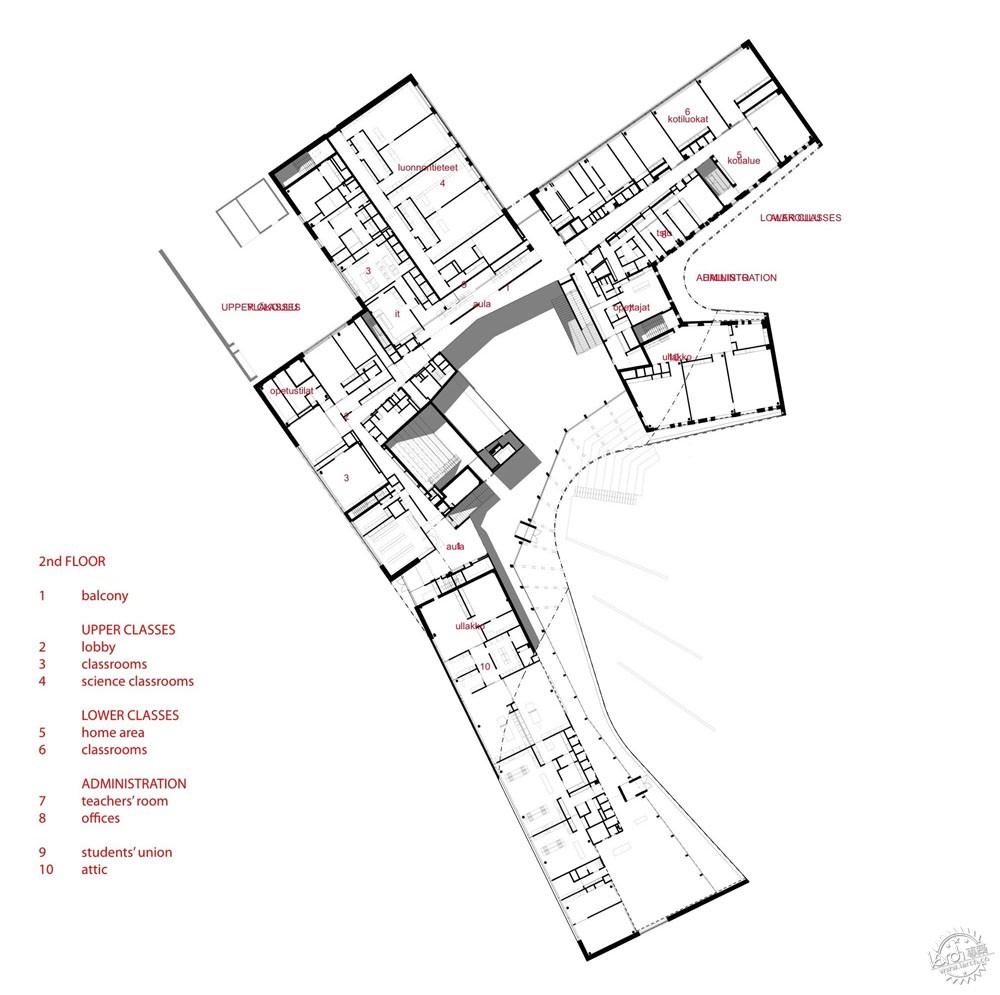

Escuela Saunalahti / VERSTAS Architects: segundo nivel. Image Cortesía de VERSTAS Architects

但是这已经是21世纪的信息时代了,老师不再是知识的守护者。随着一代又一代人们的成长,每个人都可以随时上网,在这里老师更加充当了引导者的角色,而非单纯的知识传播者,他们需要帮助学生在学习生涯中不断向前,而不是一味地指责他们。当然,这种教育模式的转变也反应在了人们的个体之中:

“那些封闭的长方形空间更加适合传统教育模式,但是对激发创意、培养创新意识的作用并不大,另外,那种空间是以老师为中心,而不是以学生为中心,没有最大限度地开发学生的各项潜力以适应现代的世界发展。”

Locker认为,学校应当具有社区感,在这里,学生们拥有必要的空间和工具,从而满足不同规模的团队生活和学习,另外,学生们也不再沉默寡言,这样可以避免一些在创造力方面滥竽充数的现象。在这些场所之中,老师们能够真正地教到他们的学生。这种教室一般为圆形,能够促进学生们的积极学习,同时加强学生之间的合作,再利用专业的电子设备和实验空间,能够让学习效率大大提升。

Nevertheless, this is the 21st century, the informational age, and teachers are no longer the guardians of the knowledge gateway. With the new generations growing up with near limitless access to the internet, teachers must take on the role of a guide rather than a gatekeeper, helping students along their educational journey rather than dragging them kicking and screaming. Of course, this shift in the educational paradigm has physical repercussions as well:

“These rectangular, closed off classrooms suit the old educational paradigm and serve little to stimulate and nurture knowledge. Furthermore, they are teacher-centered rather than student-centered and don't give students the necessary skills to navigate and flourish in the world of today. ”

Locker states that schools should foster a feeling of community, where "students have the necessary space and tools to meet in groups of all sizes and participate in active learning," and where "students are no longer anonymous and avoid problems with coexistance. These places are where the director and the teachers really get to know their students." The classrooms are circular and have everything needed to encourage active learning, from furniture that promotes collaboration among the pupils, to readily available electronic devices, to laboratories for projects.

学校:灵活、教育、公共、城市

Escuela Primaria y Centro Comunitario Legson Kayira / Architecture for a Change. Image Cortesía de Architecture for a Change

记者兼历史学家Anatxu Zabalbeascoa以及加泰罗尼亚政治科学家Judit Carrera共同指出,芬兰及其40年来的反复测试与不断失误是建筑对于教育变革影响的重要案例。

Zabalbeascoa说:“最好的学习空间一般具有记忆点,这样的场所能够建立空间与外部世界的联系,并且具有灵活性与可塑性。”Carrera指出,芬兰会将“学校看做城市、教育、政治场所”,因此,学校应当具有归属感,而对于芬兰建筑师而言,设计学习场所是值得骄傲的一件事,因为这也是在培养未来的建筑师。

然而,芬兰这种模式的成功并非一种可以简单复制的解决策略,因为真正的解决模式需要适应世界各地的不同状况。这就很像建筑学所关于背景环境的考量,其中涉及社会、经济、空间、地理,以及情感背景。举例而言,如果你不结合1917年俄罗斯独立之后芬兰人所面临的巨大文化压力,那么就无法理解芬兰的成功模式,同时也无法理解50年代以来欧洲周边国家通过工业化、消费主义、社会城市化进程来重建家园的经济压力。

School: Flexible, Educational, Public, and Urban

Journalist and historian Anatxu Zabalbeascoa along with Catalonia political scientist Judit Carrera, point to Finland and its 40 years of trial and error as an example of architecture's impact on educational reform.

Zabalbeascoa states that "the best learning spaces are those that have been designed with everyone in mind, that establish a relationship between the space and the outside world, and that is flexible and can be reinvented." Carrera points out that the Finnish "treat schools as simultaneously urban, educational, and political spaces. As such, schools should inspire a feeling of home. For Finnish architects, building a center for learning is a matter of pride and prestige," and even more so when it means educating future architects.

Nevertheless, Finland's success isn't a one size fits all solution. It's not a franchise to be replicated nor a prescription to be taken around the world, no matter how tempting it may seem to do so. Much like a lesson in architecture...it's all about context. Yes, social, economic, spatial, geographic, and perceptual context. For example, you cannot understand the success of the Finnish model without looking at the fierce cultural pressure faced by the Finns after gaining their independence from Russia in 1917, not to mention the years of economic hardship throughout the 50s while its European neighbors rebuilt themselves through industrialization, consumerism, and the progressive urbanization of society.

New City School, Frederikshavn / Arkitema Architects: primer nivel. Image Cortesía de Arkitema Architects

New City School, Frederikshavn / Arkitema Architects . Image Cortesía de Arkitema Architects

芬兰教育政策专家Pasi Sahlberg近期接受了一位智利记者的采访,内容关乎40年前改变芬兰政策的历史背景,他说:“在1970年,我们都没有受到什么教育,我们是个贫穷的农业国家,因此需要发展教育来促进国家的繁荣与安全。”

新闻界把Locker的思想和芬兰模式称为“未来的教育”,在实际情况中,当前教育模式的改革也是当代的必要问题,Mark Wigley认为,也许人们针对问题给出的回答是正确的,那么在考虑教育建筑的未来发展形式之前,人们需要扪心自问,“我们到底想要什么?我们到底要教什么?”

"In 1970, we had little education. We were a poor agricultural nation that needed education to develop our country's prosperity and security," recalls Pasi Sahlberg, a Finnish specialist in educational policy, in a recent interview with a Chilean journalist about the historical context of reforms that changed Finland some 40 years ago.

As much as the press wants to present Locker's ideas and the Finnish method as "the education of the future," in reality the need to reform the current educational paradigm is a contemporary issue. To paraphrase Mark Wigley, perhaps we are giving the correct answers to poorly asked questions. So, before thinking about how to design future (current) spaces of educational architecture, it's important to ask ourselves, "what and how do we want to teach exactly?"

|

|