由美国地质调查局拍摄的鸟瞰照片,展现了长条巨石般的普鲁特艾格社区与相邻的圣路易斯市前现代主义建筑之间的对比/An aerial photo by the US Geological Survey compares the narrow, monolithic blocks of Pruitt-Igoe with the neighboring pre-Modernist buildings of St. Louis. ImageCourtesy of Wikimedia user Junkyardsparkle (Public Domain)

AD经典:普鲁特艾格住房项目/山崎实

AD Classics: Pruitt-Igoe Housing Project / Minoru Yamasaki

由专筑网杨博,李韧编译

历史上很少有建筑如密苏里州圣路易斯市的普鲁特艾格住房项目般臭名昭著。这组建于现代主义盛行的塔楼住宅群,名义上经过改革创新,同时也是理性建筑设计战胜贫穷和社会弊病的代表作。结果,经历了二十多年的混乱之后,整个小区最终于1973年被草草拆除。普鲁特艾格的倒下不仅标志着一个公共住房项目的失败,也可以说敲响了整个“现代主义”设计时代的警钟。

Few buildings in history can claim as infamous a legacy as that of the Pruitt-Igoe Housing Project of St. Louis, Missouri. Built during the height of Modernism this nominally innovative collection of residential towers was meant to stand as a triumph of rational architectural design over the ills of poverty and urban blight; instead, two decades of turmoil preceded the final, unceremonious destruction of the entire complex in 1973. The fall of Pruitt-Igoe ultimately came to signify not only the failure of one public housing project, but arguably the death knell of the entire Modernist era of design.

普鲁特艾格崭新的住宅楼本应成为“密西西比河上的曼哈顿”/The gleaming towers of Pruitt-Igoe were to have been a “Manhattan on the Mississippi.” . ImageCourtesy of Wikimedia user Cadastral (Public Domain)

二战后的岁月里,城市人口发生变迁。普鲁特艾格这类住房项目的建设就是对这种状况的直接反应。从1920年起美国城市的增长趋势已渐趋缓慢,某些城市甚至开始负增长,密苏里州的圣路易斯市就是其中之一。更让城市专家们警觉的是,从市区向郊区转移的居民大部分属于富裕阶层,这就导致城市商业失去主顾,市政府的税收也大大减少。他们相信这种大规模的集体转移留下的空白区域最终会逐渐被贫民窟填满,而贫民窟就像是难以摘除的大毒瘤。随着1949年《住房法案》的实施,政府投资了10亿美元(当时的10亿美元比2017年的100亿美元还多),给各个城市用来进行贫民窟的清除和再开发。各种城市复兴项目以星火燎原之势横扫整个美国。[1]

1950年,圣路易斯市运用《住房法案》联邦资金,准备打造5800套保障性住房。为了追求工作效率,城市工程师Harold Bartholomew和市长Joseph Darst决定通过一个巨型小区来尽可能完成总目标。最初计划时,美国的黑人种族隔离法刚刚实行,整个项目原本是计划分成两部分:黑人居民住Wendell Olliver Pruitt 住宅,而白人居民住James Igoe公寓。然而,由于项目直到1954年才完成,此时,最高法院对“布朗对教育董事会”一案的判决已经使“平等分隔”的行为在美国境内变成违法行为。所以整个项目被整合成单独一个小区——普鲁特艾格。[2]

The construction of housing projects like Pruitt-Igoe was a direct response to the evolution of urban populations taking place in the years after World War II. The rapid growth of American cities before 1920 had slowed dramatically, and even reversed in some cities – including St. Louis, Missouri. More alarmingly for urban experts, those residents flowing out of the cities into the suburbs were largely the wealthier classes, depriving businesses of their clientele and the civic governments of their tax revenue. This mass exodus, they believed, left a vacuum which was gradually filled with slums – the dreaded “blight” which could only be cured by being expunged. With the Housing Act of 1949, $1 billion (over $10 billion in 2017) was set aside to provide cities with loans for slum clearance and redevelopment, sparking urban renewal projects across the United States.[1]

In 1950, St. Louis was preparing to create 5800 units of affordable housing with the federal funds provided by the Housing Act. City engineer Harold Bartholomew and mayor Joseph Darst, aspiring for utmost efficiency, decided to satisfy almost half of this goal with a single, massive complex. Initially planned in the twilight of the United States’ Jim Crow segregation laws, the project was to be divided along racial lines: black residents would live in the Wendell Olliver Pruitt homes, while their white counterparts would occupy the James Igoe apartments. However, as the project was not completed until 1954—after the ruling in the Supreme Court case Brown vs. Board of Education made “separate but equal” segregation illegal in the United States—it was integrated into a single complex, Pruitt-Igoe.[2]

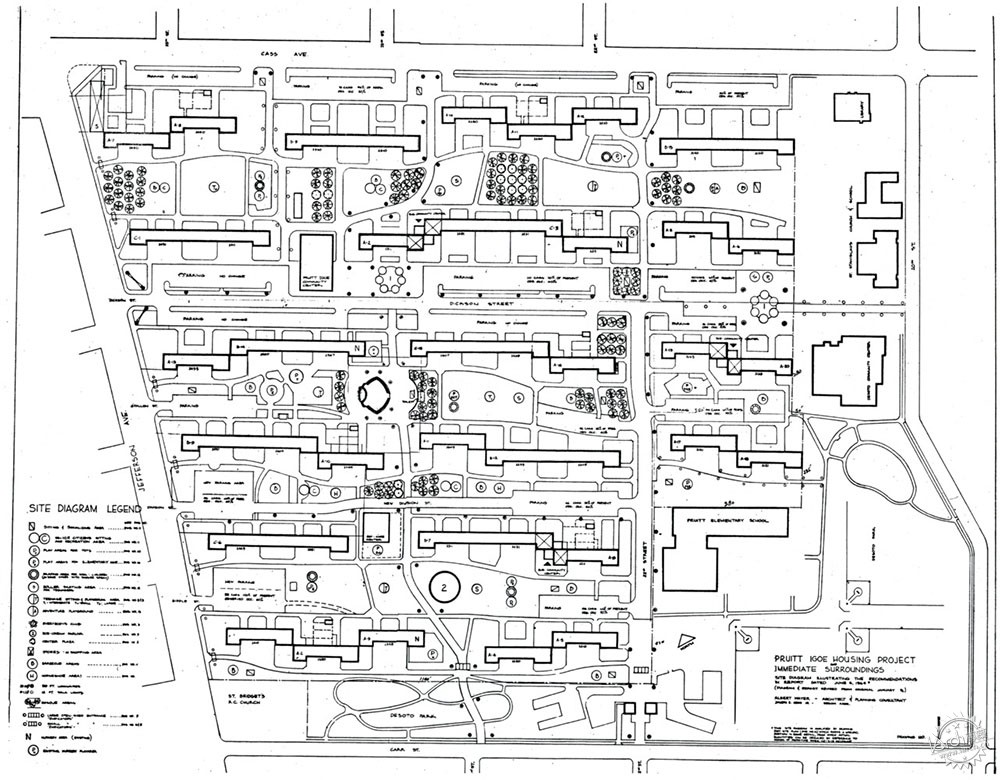

山崎实(Minoru Yamasaki)很多最初关于景观和社区福利设施的设计都没有真正建成,这也加速了普鲁特艾格最终衰落/Much of the landscaping and community amenities Minoru Yamasaki originally proposed were never built, contributing to Pruitt-Igoe’s eventual downward spiral. ImageVia pruitt-igoe.com

这个独立而巨大的项目始于对DeSoto-Carr的清除。这里曾被认为是圣路易斯最不宜居住的社区。取而代之的是Hellmuth,Yamasaki 以及Leinweber事务所的山崎实设计的由33栋11层公寓楼组成的建筑群。楼群占地57英亩(约23公顷),拥有2870套公寓,为近万人提供住处。虽然精心设计的广场加坐落其上的高层住宅的组合,深受柯布西耶的“光辉城市”概念的启发,这些建筑本身更像他后来设计的马赛公寓:窄长形的结构的长边上布置着85英尺(约26米)的长条窗。为改良功能、节约投资,跃层电梯的设计是建筑的重要特色。电梯每隔三层一停,然后有楼梯将停靠层与上下的楼层相连接。这种组合是为了将路边的社区生活引入高层建筑之中。同时,无论男女老幼都能聚集在这遮风挡雨的建筑里。[4,5]

甚至在完成之前,普鲁特艾格也没有完全按照最初的设计方案。山崎实有好几个设计建议都没有最终实施,如散布在高层中的低层公寓、运动场地、底层卫生间以及额外的景观都因联邦房管局认为太昂贵而取消。正是这种对经济因素的不断强调造成了像跃层电梯这些特色因素的存在,而这些特色正暗示着未来的困境时代。[6]

This single, enormous project began with the clearing of DeSoto-Carr, considered one of the least habitable neighborhoods in St. Louis.[3] In its place was to be built a collection of 33 modular 11-story apartment towers designed by Minoru Yamasaki of Hellmuth, Yamasaki, and Leinweber. Occupying 57 acres of land, the towers provided accommodation for up to 10,000 residents in 2,870 apartment units. While the composition of residential high-rises towering over manicured plazas drew heavy inspiration from Le Corbusier’s Ville Radieuse concept, the buildings themselves more closely resemble his later Unité d’Habitation projects: long, narrow slab structures with window galleries running 85 feet along their length. One notable feature designed to improve both functional and cost efficiency were the skip-stop elevators, which only opened onto every third floor. Staircases then provided access to the floors immediately above and below. The combination of the two was intended to replicate community life on the sidewalks in a high-rise setting, where children and adults alike could gather in sheltered safety.[4,5]

Even before it was completed, Pruitt-Igoe was not built as intended. Yamasaki had proposed a number of design elements which were never built: low-rise units dispersed among their larger counterparts, playgrounds, ground-floor restrooms, and additional landscaping were all deemed too expensive by the Federal Housing Administration and cut from the project. It was this constant emphasis on economy that dictated features like the skip-stop elevators, and which only hinted at the troubled times ahead.[6]

Courtesy of "The Pruitt Igoe Myth"

Courtesy of "The Pruitt Igoe Myth"

虽然普鲁特艾格在最初并没有按照获奖项目的一般特点来设计建造,但它的设计仍获得不少报刊杂志的赞赏。比如,《建筑论坛》就称它为1951年度“最佳高层公寓”。(1965年这家杂志又重新审视了普鲁特艾格并改变立场,称它为一个失败的项目。)不幸的是,虽然联邦政策已经废除了合法的种族隔离,然而包括不少圣路易斯人在内的很多美国人的观念却还没有完全转变,普鲁特和艾格公寓的整合导致了大多数白人居民的集体出逃,甚至连能负担得起别处独院住宅的黑人也选择了离开。住宅中剩下的租户全都是穷得无处可去的特困家庭。[7]

后来,普鲁特艾格开始逐渐衰败。1957年居住率最高时,整个小区的非居住率甚至只有9%,到了1960年,这个数字攀升到16%,随后迅速增加到1970年的65%。虽然联邦政府提供资金建成了普鲁特艾格,它的维护却直接依赖于租户的租金。而许多租户还在靠社会福利维持生活,几乎没钱来维护这33栋塔楼。于是,整个形势变成了一种恶性循环:糟糕的住宅环境逼走了更多的租户,从而造成已经十分缺乏的预算变得更少,导致住宅变得越来越破旧,然后又逼走更多的租户。[8,9]

Although Pruitt-Igoe was by no means an award-winning project even at the time of its opening, its design was nonetheless lauded by publications like the Architectural Forum, which had named it the Best High Apartment in 1951. (In 1965, this same magazine reexamined Pruitt-Igoe and reversed its stance, declaring the project a failure.) Unfortunately, while federal policy had struck down legal segregation, the attitudes of many Americans—including many of those living in St. Louis—had yet to catch up. The integration of the Pruitt and Igoe apartments resulted in most of the white residents leaving en masse, along with those black residents who could afford single-family dwellings elsewhere. The only tenants left were those who literally could not afford to go anywhere else.[7]

Pruitt-Igoe’s fall from grace began almost immediately. At its peak occupancy in 1957, 9% of the complex remained vacant; by 1960, this figure climbed to 16%, and it later skyrocketed to 65% by 1970. Whereas the federal government had provided the funds to build Pruitt-Igoe, its maintenance was to be supported directly by the tenants’ rent. With the apartments occupied almost exclusively by a dwindling number of low-income residents, a number of whom subsisted on welfare, there was little money to keep up the 33 towers, and they subsequently fell into disrepair. The situation became a vicious cycle: poor maintenance drove out more tenants, bleeding out the already-strained budget and allowing the buildings to become more and more derelict, repelling even more tenants.[8,9]

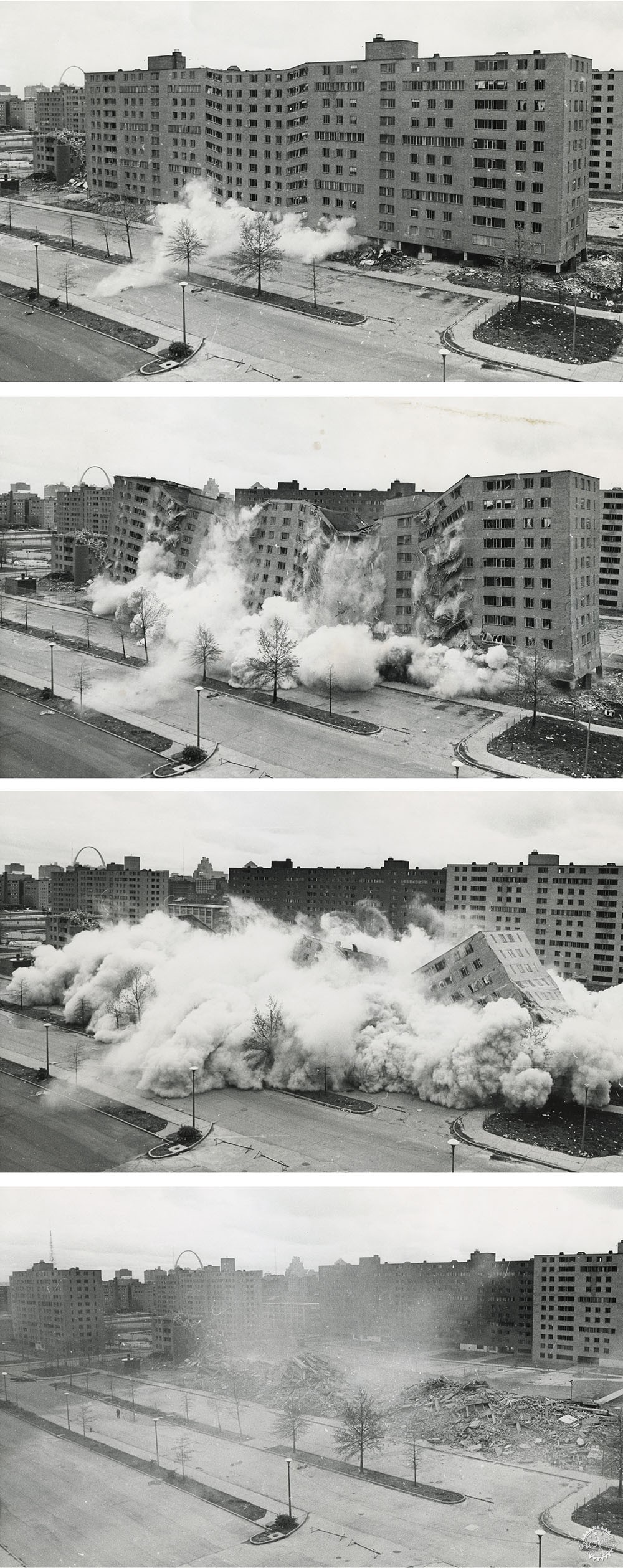

伴随着犯罪和维护问题不断增加,20年之后,普鲁特艾格最终在1972到1977年之间被拆除/After two decades of crime and increasing maintenance issues, Pruitt-Igoe was ultimately demolished between 1972 and 1977. ImageVia pruitt-igoe.com

Courtesy of Wikimedia user Cadastral (Public Domain)

正是在这种气氛下,普鲁特艾格变成了犯罪活动的温床。本来为提供安全的社区空间而建的走廊和楼梯间反而变成了黑帮的领地,居民们称这些走廊为“夹道鞭笞”,因为人们在这些走廊上常常会遭到骚扰甚至侵犯。因此,小区的声誉急剧下降,以至于一些维护员和快递员都拒绝进入。直到1958年,圣路易斯住房管理局请求联邦政府拨款改造普鲁特艾格。虽然山崎实的一些最初设计概念随后在1965年建成,但后来的改造并没有从根源上解决问题,普鲁特艾格仍然迅速陷入更加惨淡的窘境。[10]

1972年,联邦政府最终决定拆除普鲁特艾格。于是接下来的几年里,33栋塔楼通过火药爆破的方式被逐一拆除,从此在圣路易斯的城市里留下了一片广阔的废弃地面,这片区域直到今天还空着。拆除命令下达的时候,小区里只住了600人,比最初设计时期望的10000人相差甚远。普鲁特艾格的衰落变成了一个标志:这不只代表着一个住房项目的失败,也不只代表着这类项目总体上的失败,而是代表着现代主义建筑本身的失败。广为流传的是建筑评论家查尔斯•詹克思(Charles Jencks)的说法:“1972年7月15日下午3点32分,现代主义建筑死于密苏里州圣路易斯市。”在《建筑评论》的一篇采访中,关于普鲁特艾格,山崎实只是轻描淡写地说道:“这个项目当初还不如不做。”[12]

It was in this atmosphere that Pruitt-Igoe became a hotbed for criminal activity. The galleries and staircases meant to provide safe community spaces instead became the dominion of gangs; residents nicknamed the galleries “gauntlets,” treacherous passages in which they were harassed or even assaulted on their way home. The complex’s reputation soured so dramatically that some maintenance and delivery workers refused to enter. By 1958, the St. Louis Housing Authority petitioned the federal government for funding to renovate Pruitt-Igoe; although some of Yamasaki’s originally-intended amenities were subsequently installed in 1965, the renovation failed to address the deeper social and fiscal issues which had caused Pruitt-Igoe’s prompt nosedive into squalor.[10]

In 1972, the federal government finally determined that Pruitt-Igoe was beyond rescue. Over the next few years, the 33 towers were demolished by means of dynamite implosions, leaving behind a vast urban wasteland in the fabric of St. Louis which, to this day, has yet to be filled. Only 600 residents had been left when the order came, a far cry from the 10,000 originally expected to fill the complex. The fall of Pruitt-Igoe came to be seen as symbolic: more than the failure of one housing project, and more than the failure of the such projects in general, it was touted as the failure of Modernist architecture itself. Architecture critic Charles Jencks famously declared, “Modern architecture died in St. Louis, Missouri on July 15, 1972, at 3.32 pm.”[11] In an interview for Architectural Review, Minoru Yamasaki said simply of Pruitt-Igoe: “It’s a project I wish I hadn’t done.”[12]

电视直播的普鲁特艾格的爆破画面激发了大众对于导致了该项目如此失败的原因的广泛讨论/The televised demolition of Pruitt-Igoe sparked widespread discussion over what precisely caused the project to fail so dramatically. ImageCourtesy of Wikimedia user Cadastral (Public Domain)

归根结底,普鲁特艾格的失败不能全怪建筑设计,但是也与建筑设计息息相关。是不合时宜的设计方式,加上根深蒂固的种族思想,再加上混乱的住房政策,最终导致普鲁特艾格的20年乱局。从此以后,一片树林茁壮生长在这曾经耸立着33栋塔楼的土地,掩盖了这片20世纪70年代拆除之后留下的大地裂痕。但是,这些塔楼毕竟曾经存在过,不论人们把普鲁特艾格的衰落归咎于何种原因,“普鲁特艾格”这个名字仍将成为设计哲学上整体失败的代名词。

In the end, it is as unfair to place sole blame for Pruitt-Igoe’s failure on its architectural design as it would be to completely exonerate it. It took the combination of unfortunate design choices, deep-seated racism, and poorly-structure housing policy to produce the twenty-year fiasco that was Pruitt-Igoe. A forest has since grown on the land where the 33 towers once stood, disguising the physical rift they left after their destruction in the 1970’s. Their legacy is not so easily disguised, however, and whomever one chooses to blame for its eventual downfall, the name Pruitt-Igoe remains synonymous with the failure of an entire design philosophy.

引用参考

[1] Bauman, John F., Roger Biles, and Kristin M. Szylvian. From Tenements To The Taylor Homes: In Search Of An Urban Housing Policy In Twentieth-Century America. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2000.

[2] Sennott, R. Stephen. Encyclopedia of 20th Century Architecture. New York: Fitzroy Dearborn, 2004. p1066.

[3] Bauman et al, p186.

[4] Frishberg, Hannah. "The Failed Paradise: Pruitt-Igoe." Atlas Obscura. November 26, 2013. [access].

[5] Sennott, p1066.

[6] Sennott, p1066.

[7] Marshall, Colin. "Pruitt-Igoe: The Troubled High-rise That Came To Define Urban America – A History Of Cities In 50 Buildings, Day 21." The Guardian. April 22, 2015. [access].

[8] Bauman et al, p201.

[9] Frishberg.

[10] Bauman et al, p201.

[11] Frishberg.

[12] Marshall.

References

[1] Bauman, John F., Roger Biles, and Kristin M. Szylvian. From Tenements To The Taylor Homes: In Search Of An Urban Housing Policy In Twentieth-Century America. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2000.

[2] Sennott, R. Stephen. Encyclopedia of 20th Century Architecture. New York: Fitzroy Dearborn, 2004. p1066.

[3] Bauman et al, p186.

[4] Frishberg, Hannah. "The Failed Paradise: Pruitt-Igoe." Atlas Obscura. November 26, 2013. [access].

[5] Sennott, p1066.

[6] Sennott, p1066.

[7] Marshall, Colin. "Pruitt-Igoe: The Troubled High-rise That Came To Define Urban America – A History Of Cities In 50 Buildings, Day 21." The Guardian. April 22, 2015. [access].

[8] Bauman et al, p201.

[9] Frishberg.

[10] Bauman et al, p201.

[11] Frishberg.

[12] Marshall.

建筑设计:山崎实事务所

地点:美国密苏里州圣路易斯市卡斯大道2300号

主创建筑师:山崎实

项目年份:1954年

Architects: Minoru Yamasaki Associates

Location: 2300 Cass Ave, St. Louis, MO 63106, United States

Architect in Charge Minoru Yamasaki

Project Year: 1954

出处:本文译自www.archdaily.com/,转载请注明出处。

|

|