Image © Pedro Kok

居住组团:设计联系情感

Socially-Organized Housing: Design That Establishes Emotional Ownership

由专筑网王雪纯,曹逸希编译

该文章由Nikos A. Salingaros,David Brain,AndrésM. Duany,Michael W. Mehaffy和Ernesto Philibert-Petit撰写,提供了一套基于现实依据的最优廉租房实践方法,且普遍适用。文章在拉丁美洲的背景下分析了不同的案例。适应性解决方案致力于实现长期可持续发展,并帮助居民了解其建筑环境。

随后,文章提出了对复杂性科学的新见解,比如对于Christopher Alexander关于如何成功地发展城市形态一文的思考。文章通过应用“模式语言”和“生成代码”的概念工具,表达了对其他人先前提供的解决方案的支持,虽然这些解决方案从未以可行的形式提出。

世界各国政府之前所青睐的标准廉租房类型是失败的,因为它是不人性化的,是不可持续的。而文中提出的新方法则提供了一种新的替代方案。

这一系列文章概述了廉租房新的解决方案。文章是一位巴西作者NAS所编写的综合报告,适用于整个拉丁美洲。其中一位作者AMD正在牙买加和加勒比地区的其他地区设计廉租房。其中两位作者AMD和MWM直接参与了美国南部卡特里娜飓风灾难后的重建工作,该地区面临着与廉租房类似但不完全相同的处境。另一位作者EPP正在研究城市结构的行人连通性,并参与了墨西哥政府援助的住房解决规划。而作者DB长期研究城市形态对社会福祉和社区可持续性的影响,这也是文中讨论的一个关键因素。

Developed by Nikos A. Salingaros, David Brain, Andrés M. Duany, Michael W. Mehaffy, and Ernesto Philibert-Petit, this series of articles offers here a set of evidence-based optimal practices for social housing, applicable in general situations. Varying examples are discussed in a Latin American context. Adaptive solutions work towards long-term sustainability and help to attach residents to their built environment.

They propose, then, new insights in complexity science, and in particular the work of Christopher Alexander on how to successfully evolve urban form. By applying the conceptual tools of “Pattern Languages” and “Generative Codes”, these principles support previous solutions derived by others, which were never taken forward in a viable form.

New methodologies presented here offer a promising alternative to the failures of the standard social housing typologies favored by governments around the world, which have proven to be dehumanizing and ultimately unsustainable.

This series of articles outlines promising new solutions for the future of social housing. It has been prepared as a comprehensive report by one of the authors (NAS) for Brazil, and is generally applicable to all of Latin America. One of us (AMD) is designing social housing in Jamaica and elsewhere in the Caribbean. Two of the authors (AMD & MWM) are directly involved with the reconstruction after the hurricane Katrina devastation in the Southern United States, which faces similar, though not identical, realities. Another author (EPP) has researched the pedestrian connectivity of the urban fabric, and is involved in providing government-assisted housing solutions on a massive scale in Mexico. The remaining author (DB) has long studied the influence of urban form on social wellbeing and community sustainability, a crucial factor in our discussion.

Image © Ana Cecilia Garza Villarreal

如果一个项目得到居民的维护和喜爱,那么该项目就是成功的

全世界的城市化进程导致廉租房面临着挑战,我们希望在此提出一种全面的方法,从根本上改善其效果。项目是否成功,取决于居民的身心健康。我们认为,如果一个项目得到居民的维护和喜爱,并且城市结构以健康和互动的方式建立,那么项目就会成功。相对的,我们认为被居民憎恨的项目是不成功的(因此是不可持续的),导致项目失败的原因可能是在初始建设和维护中浪费了资源,导致社会退化,使居民与社会隔离,从而使项目在短时间内就衰弱下去。

A project is successful if it is maintained and loved by its residents

The challenge of social housing is a major component of world urban growth, and we wish to present here a comprehensive methodology for radically improving its performance. Success will be measured in human terms: i.e., the physical and emotional wellbeing of the resident. We consider a project to be successful if it is maintained and loved by its residents, and also if the urban fabric joins in a healthy and interactive way to the rest of the city. On the other hand, we consider as unsuccessful (and hence unsustainable) a project that is hated by its residents for a number of different reasons, wastes resources in initial construction and upkeep, contributes to social degradation, isolates its residents from society, or decays physically in a short period of time.

Image Cortesía de Natura Futura Arquitectura

这里介绍的方法的实质是应用可持续的过程,而不是只是用特定的形式(IMAGE)来设计和建造,即根据准备好的图像来建造和排列建筑。相比之下,我们的方法从一开始就没有特定的形式:它从过程本身出现,只有在一切都完成后才会清晰。

我们可以借鉴Christopher Alexander(提出城市结构应该遵循有机范式的先驱者之一)的思路,或者可以借鉴一些由于各种原因未被广泛应用的理论和实践工作,从而提出更彻底和令人满意的解决方案。根据几个世纪以来传统实践的许多例子的事实依据,刚好可以证明我们的方法可行。相反,政府敲定的方案往往是那些会使得居住者对廉租房结构产生敌意的方案。我们将分析造成这种敌意的原因,以便将来防止这种情况的发生。这里介绍的解决方案是相对简单的,也是通用的,虽然背景是拉丁美洲,它仍然可以被世界其他地方采纳,只需稍加修改即可。本研究概述了普遍适应于哪怕由于当地情况不同而出现的造房不同的设计策略。

The essence of the approach presented here is to apply a sustainable PROCESS rather than a specific IMAGE to design and building. The way it was done in the recent past is to build according to a prepared image of what the buildings ought to look like, and how they should be arranged. By contrast, no image of our project exists at the beginning: it emerges from the process itself, and is clear only after everything is finished.

We can move toward a more thorough and satisfying solution by drawing upon Christopher Alexander’s work — one of several pioneers who proposed that urban fabric should follow an organic paradigm — and can include theoretical and practical work that for various reasons is not widely applied. What we offer is supported by the evidence from many examples of traditional practice over centuries. Governments instead choose to impose schemes and typologies that ultimately generate hostility for the fabric of social housing from its occupants. We will analyze the reasons for this hostility in order to prevent it in the future. The relatively simple solutions presented here are generic. Therefore, though geared to Latin America, they can be adopted by the rest of the world with only minor modifications. This study outlines ideas that are general enough to apply to countries where local conditions that produce housing might be very different.

Image © Ana Cecilia Garza Villarreal

我们可以从政府资助住房的创新方法中学习,这些住房是由独立团体在不同环境条件下开发的。在几十年来建成的许多项目中,根据我们对居民身心健康的标准,很少有项目是真正“成功”的。那些极好的解决方案往往被忽略,因为它们无法满足某些标志性特征(我们将在本文后面详细讨论)。事实上,我们还借鉴了开发可持续高收入社区所采用的成功类型学。

利用“复杂性管理”方法

本文结合了两种互补的方法(并将这些方法与现有方法进行对比)。一方面,我们将为建设廉租房提供一些明确的实践准则。任何即将开始建设廉租房的团体或机构都可以通过适当的修改将这些准则融入进当地的建设。另一方面,我们将提出社会住房及其文化含义的一般哲学和科学背景。这个理论的目的是“允许”常识论证、创造条件,以安全和自然的方式提高效率。本地居民其实早就懂得几千年来先辈们成功建造住房的方法:将住房作为健康居民建造社区生产的一部分。

We can learn from innovative approaches to government-sponsored housing, developed by independent groups in many different settings and conditions. Out of many projects built over several decades, very few can be judged to be truly successful using our criteria of the residents’ physical and emotional wellbeing. Those few excellent solutions tend to be neglected because they fail to satisfy certain iconic properties (which we discuss in detail later in this paper). Perhaps surprisingly, we also draw upon successful typologies developed for sustainable upper-income communities.

Utilizing a “complexity-managing” approach

This paper combines two mutually complementary approaches (and will contrast these with existing methods). On the one hand, we will give some explicit practical rules for building social housing. Any group or agency wishing to get started immediately may implement these — with appropriate local modifications — on actual projects. On the other hand, we will present a general philosophical and scientific background for social housing and its cultural implications. The aim of this theoretical material is to “give permission” for common-sense arguments; to create the conditions that will safely allow and support what in effect comes naturally. People, acting as intelligent local agents, may then apply methods that evolved during millennia of successfully performing owner-built housing — as part of the production of healthy resident-built communities.

Image Cortesía de Archivos T3 ALBORDE

该方法通过利用“复杂性管理”方法,而不是 “自上而下”的线性方法,从而识别并结合历史上最强大的人类住区的自组织特征。我们建议在我们管理的系统中引导设计人才和招揽本身有能力的当地人来组织领导,这个系统只是为了帮助生成和指导其不断变化的复杂性。在这种方法中,尽管在基于先前经验的约束内,但也能允许“自下而上”过程有机地发展。另一方面,“自上而下”的干预必须通过仔细的实验(即通过反馈)来进行,允许与较小规模的“自下而上”过程进行更多的互动。

This methodology recognizes and incorporates the self-organizing features of the most robust human settlements throughout history, by utilizing a “complexity-managing” approach, rather than a linear, “top-down” approach. We propose channeling the design talent and building energy of the people themselves, acting as local agents, within a system that we manage only to help generate and guide its evolving complexity. In such an approach, “bottom-up” processes are allowed to develop organically, though within constraints based upon prior experience. On the other hand, “top-down” interventions must be done experimentally and carefully (i.e., with feedback), allowing more interaction with smaller-scale “bottom-up” processes.

Image Cortesía de Archivos T3 ALBORDE

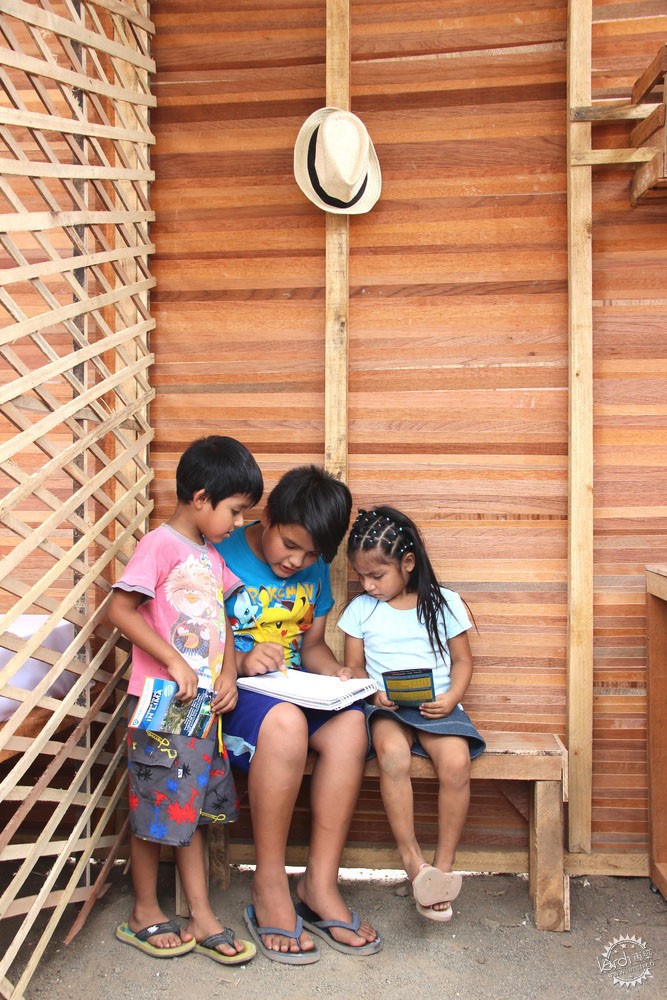

我们的愿景不只在于业主如何去浇筑混凝土,如何去修建建筑,还在于他们设计和构建建筑的过程。业主需要与住宅建立联系,并参与设计过程。这样的愿景的重点是让业主能够适应,所以这个过程必须是足够灵活的,且可以确保不会受到不平等的社会动态驱动的影响从而导致项目失败。最重要的是,该流程可以利用技术和专业知识。我们提出的不仅仅是让人们自给自足,我们希望赋予他们对新技术和对城市形态的理解。

过时的早期工业模式

正如许多先驱的描述(例如Alexander(1977),Jacobs(1961),Turner(1976)等人),已经落成的那些规划更像是过时的早期工业模式。这种模式出现在20世纪20年代,在二战后被广泛采用。它基于分层的“自上而下”命令和控制范例,从而起到预测的作用并提供规划范本。经过研究充分证明,这种模式并不能反映城市问题,因为该模式忽视了作为一个成功的城市结构所需要的庞大物理和社会复杂性。此模式甚至没有解决人类与建筑环境的互动,其导致的故障和意外后果是有详细记录的。随着科学的发展,人们可以用更精密和更准确的研究工具来研究这种自组织现象(包括城市中的现象),对于当下而言,提出一种激进的新城市主义是有必要的。我们希望以最近的城市研究为事实依据,向人们说明这种新方法的权威。

Our proposal goes beyond housing that is literally owner-built In the sense that owners hammer nails and pour concrete. It is important that they experience the process of design and building as THEIR process. It’s all about establishing connection and engagement. The key point is a process that accommodates real engagement, that is agile enough to be responsive to adaptive processes, and that can engage without being driven by the social dynamics of inequality into unfortunate directions. Most important, the process can take advantages of both technology and expertise. We are proposing something far more than letting the poor fend for themselves — we wish to empower them with the latest tools and a highly sophisticated understanding of urban form.

An outmoded early industrial model

As many authors have described previously (e.g. Alexander et. al. (1977), Jacobs (1961), Turner (1976)), established planning practice has tended to follow an outmoded early industrial model. That model arose in the 1920s, and was widely adopted in the period following World War II. It was based upon a hierarchical “top-down” command-and-control paradigm, leading to predict-and-provide planning. Research amply demonstrates that this model does not sufficiently reflect the kind of scientific problem a city poses, because the model ignores the tremendous physical and social complexity of successful urban fabric. Incredibly, it does not even address human interactions with the built environment. The resulting failures and unintended consequences are well documented. As science develops more fine-grained and more accurate research tools for the analytical study of such self-organizing phenomena (which include cities), it is necessary now to propose a radical new urbanism. We wish to empower people with the authority of a new methodology, grounded in recent urban research.

Image © The Photographer. Vía Wikimedia, licensed by CC BY-SA 3.0

城市存在的问题不仅在于缺乏物理复杂性。城市场所建设的关键在于空间形式的复杂性与社会过程的复杂性之间的关系。如果它只是物理复杂性的问题,可以想象出可以创建一个自上而下的过程来模拟这种复杂性—— 就像计算机算法一样。关键的一点是,这种物理复杂性表达并体现了社会生活。在某些方面,它会通过文物和建筑空间之间的关系等类似的方法来体现一种社会关系。所以,答案是首先将建筑环境构思为社会过程,而不仅仅是产品或容器。“维护”是很重要的一点,因为居民只有在真正入住后才会去开始“维护”。

生态系统类比

这是一个基本上不相容的矛盾:有机城市结构是人类生物学的延伸,而有计划的结构是人类对自然强加的人造视觉。前者充满了生命,虽然可能是贫穷和不卫生的,而后者往往是干净有效且无菌的。这两种截然不同的城市形态中皆有利弊,但它们都可以达到某种平衡共存(如拉丁美洲大部分地区)。在“自建”运动中,政府允许业主建造自己的房屋,并提供培训和建筑材料,帮助建立电力,水系和污水处理系统。

The problem isn’t just the lack of physical complexity. The key to urban place making is really the relationship between the complexity of spatial form and the complexity of social process. If it were just a matter of physical complexity, one might imagine that a top-down process could be created to simulate that complexity — say, a computer algorithm. The crucial point is that this physical complexity embodies and expresses social life. It is, in certain respects, social relations by other means (e.g., artifacts and built spaces). To some extent, the answer begins by re-conceiving the built environment itself as social process, not just as product or container. This becomes important later when we talk about maintenance, since the processual character of this kind of ownership merely begins when residents move in.

The Ecosystem Analogy

Here is a basic incompatibility: organic urban fabric is an extension of human biology, whereas planned construction is an artificial vision of the world imposed by the human mind on nature. The former is full of life but can be poor and unsanitary, whereas the latter is often clean and efficient but sterile. One of these two contrasting urban morphologies can win out over the other, or they could both reach some sort of equilibrium coexistence (as has occurred in most of Latin America). In the movement for “self-construction”, the government accepts that owners will build their own houses, and provides materials and training to help establish the networks of electricity, water, and sewerage.

© Hogar de Cristo. Via Wikimedia, licensed by CC BY-SA 4.0

“廉租房”通常被理解为由政府或非政府组织建造的资助项目。住户可以购买他们的住宅,通常的做法是以补贴后的低租金租用,甚至免费提供。在后一种情况下,居民的生活空间受到不同程度的限制。而前者会容易导致住户非法扩建的行为。由于擅自占地的居民点是非法的,政府一般会拒绝住户合法购买土地的请求。在大多数情况下,政府同样不允许这些住宅连接到城市其他地方的公用电网(电,水和污水处理系统)。结果,那里的生活条件是和平时期定居点中最差的。

“Social housing” is usually understood as a project for housing the poor, built and financed by a government or non-governmental organization. Occupants could purchase their units, but a usual practice is to rent them at low subsidized rents, or even to provide them for free. In the latter instances, the residents live there by courtesy of (and are subject to varying degrees of control by) the owning entity. A “squatter settlement”, on the other hand, is a self-built development on land that is not owned by the residents, and which is frequently occupied without permission. Since squatter settlements are illegal, the government generally refuses to provide the means of legally purchasing individual plots of land. In most cases, it also refuses to connect those residences to the utility grid (electricity, water, and sewerage) of the rest of the city. As a result, living conditions there are the worst among peacetime settlements.

Image © Solène Veysseyre

全世界中,十亿以上贫困人口是居住在廉租房和平房区等地区。我们将并肩讨论这两种城市现象,并提出解决两者之间的思想和空间矛盾。作为一个基本出发点,贫困人口住房处于世界城市生态系统的最低水平。人类社会中的不同力量产生了两种类型的城市体系:政府支持的廉租房,或者是平房区。 Christopher Alexander(2001-2005),Hassan Fathy(1973),N。J. Habraken(1972),John F. C. Turner(1976)以及其他先驱认同了这样的构想,并提出了两种系统的适应性。Turner在秘鲁和墨西哥建立了几个项目,并提倡其他人在全球范围内实施这些想法。

自建平房与政府廉租房之间的竞争

生态系统的类比也在一定程度上证明了政府对于非法营建的行为的警惕性。非法营建者如果不受法律限制和直接干预,会迁入私人和公共土地。我们所面对的是同一可用空间的物种竞争(来自城市类型学中的理论)。每个物种都希望取代所有其他物种。如果不受管辖,棚户区可以占领整个城市(例如,在开罗,他们已经占领了商业建筑的平屋顶;在美国,人们在公园和高速公路立交桥下建造临时避难所)。反过来,政府希望清除所有的非法营建。世界各国政府都认为他们必须建造有计划的住房来取代非法营建的住房。然而这样的巨额花销是难以承受的。

如果没有中央控制,一个城市能像真正的有机系统一样,自然会更好。然而,适应竞争的城市系统从未有过标准做法。虽然关于传统定居点的基本思想已经到位,但传统思想缺少一些关键要素。我们现在提供住房专业知识作为DYNAMIC流程(通过将模式语言与生成代码相结合:见下文)。新住房项目需要从头开始进行干预。同样,这种动态过程也可以应用于已建成的环境,通过寻求一个可使他们满意的生活条件水平来改善非正式的无计划住房项目(贫民窟或其他)。

Social housing and squatter settlements are regions where more than one billion of the world’s very poor live. We are going to discuss these two urban phenomena side-by-side, and offer to resolve the ideological and spatial competition between the two. As a basic starting point, housing for the poor represents the lowest level of the world’s urban ecosystem. Different forces within human society generate both types of urban system: either government-sponsored social housing, or squatter settlements. Christopher Alexander (2001-2005), Hassan Fathy (1973), N. J. Habraken (1972), John F. C. Turner (1976), and others recognized this competition before us, and proposed an accommodation of the two systems. Turner helped to build several projects in Peru and Mexico, and advised others on implementing such ideas worldwide.

Competition between owner-built settlements and government-built social housing

The ecosystem analogy also explains and to a certain extent justifies the vigilance by which governments prevent squatter settlements from invading the rest of the city. If not restrained by law and direct intervention, squatters move into private and public land. We are describing a species competition for the same available space. Each species (urban typology) wants to displace all the others. Squatter settlements can take over the entire city if allowed to do so (for example, in Cairo, they have taken over the flat roofs of commercial buildings; in the USA people build temporary shelters in public parks and under highway overpasses). The government, in turn, would like to clear all squatter settlements. Governments the world over assume that they must construct planned housing to replace owner-built housing. That is too expensive to be feasible.

Like all truly organic systems, cities are better off without central control. Accommodating competing urban systems never became standard practice, however. Although the basic ideas about traditional settlements were in place, several key elements of understanding were previously missing. We are now offering expertise in housing as a DYNAMIC process (by combining pattern languages with generative codes: see later sections). Interventions are needed, starting from scratch in new housing projects. The same dynamic process can also be applied to already built environments, in seeking to adapt a large number of informal unplanned housing projects (favelas or others) by bringing them up to acceptable living conditions.

Image © Solène Veysseyre

竞争发生在使用城市土地或从中获利的所有经济阶层(“物种”)之间。在拉丁美洲,城市土地的投标留下了大量未开发的土地,所有已经到位的服务都被浪费掉了。然而最贫困的人口只能去郊区找土地,并为水和其他服务支付高昂的价格,并没有办法享受住在他们的主要收入来源(中心城市)生活的好处。这给政府带来了严重的问题。比起将这种做法描述为“不公平”(不会导致任何变化),我们更愿意为政府指出这会导致未来的巨大累积成本。

多年来,在试行的各种社会住房计划中,人们普遍认为非法营建的贫民窟令政府感到尴尬,必须尽快用推土机将其推平。然而这种想法是错误的。很少有权威人士考虑现有棚户区的经济优势。建筑物,地块和街道模式的几何形状在很大程度上是有机地发展(演化)的,公正地说,这种自组织其实提供了许多非常理想的特征。贫民窟有着严重的缺陷,也正因如此,它为居民提供了经济,高效,快速的自发示范。

贫民窟有自我修复机制

贫民窟的缺点不是城市系统本身所固有的。它们的有机几何形状非常完美,但同时,它也因为其集合形状被强烈拒绝。它根本不适合渐进式城市结构应该类似的刻板印象——整洁,光滑,矩形,模块化和洁净。贫民窟的有机几何与蹲坐的非法行为有关,并且几乎是普遍存在的现象。几何形状本身代表了政府理论中“进步的敌人”。在我们克服偏见之前,我们无法建立生活都市面料(或保存现有部分)。大多数自上而下的社会住房计划缺乏自我修复机制。有机增长也在自然过程中修复着城市肌理,事实上没有任何住房项目是完全刚性的。

Competition occurs among all economic strata (“species”) that either use urban land, or profit from it. In Latin American cities, urban land speculation leaves a large amount of undeveloped land with all the services already in place wasted. The poorest population then has to find plots on the outskirts, and pay steep prices for water and other services, without having the benefit of living close to their main source of income (the central city). This creates a severe problem for the government. Rather than characterizing the practice as “unfair” (which does not lead to any change), we point out its tremendous cumulative costs for the future.

Throughout all the various schemes for social housing tried over the years, it is widely accepted (with only a few exceptions) that the unplanned owner-built favela is embarrassing to the government, and has to be bulldozed as soon as possible. Yet that assumption is wrong. Very few in a position of authority seem to consider the urban and economic advantages of existing shantytowns. The geometry of buildings, lots, and street patterns has for the most part developed (evolved) organically, and we will argue here that this self-organization affords a number of very desirable features. With all its grave faults, the favela offers an instructive spontaneous demonstration of economic, efficient, and rapid processes of housing people.

The favela has a self-healing mechanism

The favelas’ disadvantages are not inherent in the urban system itself. Their organic geometry is perfectly sound, yet it is precisely that aspect which is vehemently rejected. It simply doesn’t fit into the stereotyped (and scientifically outmoded) image of what a progressive urban fabric ought to resemble — neat, smooth, rectangular, modular, and sterile. A favela’s organic geometry is linked with the illegal act of squatting, and with a pervasive lawlessness. The geometry itself represents “an enemy to progress” for an administration. We cannot build living urban fabric (or save existing portions) until we get past that prejudice. The favela has a self-healing mechanism absent from most top-down social housing schemes. Organic growth also repairs urban fabric in a natural process, something entirely absent from geometrically rigid housing projects.

Image © Sara Ulloa

具有讽刺意味的是,贫民窟的有机几何形态通常与现代国家左翼和右翼的命令不一致,因为它可以以适当控制的方式回应社会问题。一些对控制的兴趣与社会控制相关的理性行政秩序有关。这反映出国家需要通过证明其合理性来使其干预合法化,或者需要在分配公共资源时维持官僚机构的问责制,或者尊重私有财产惯例。它也可能是一种真诚的关切人民的改革理论,以民主原则为动机,以一种既有效又程序公正的方式提高贫穷人口的生活水平。

有序几何图形给出了对建筑的控制形成的图像。无论这是故意(显示国家的权威)还是潜意识(从建筑书籍中复制图像),政府和非政府组织都倾向于通过建筑来看待他们自己的“理性”。偏离这一类型会被认为是忽略权威。它提出了关于资源分配合法性的可能问题,这些问题不受严格的官僚会计程序的约束。

这两者都被避免了,因为它们往往侵蚀了国家的权威,特别是私有财产权是法律和监管制度的重要组成部分。形态复杂的棚户区通常完全不受政府控制。主张控制权的一种方式是将居民迁移到政府建造的住房。而这种方式有时显得很令人悲伤,比如非洲的各个政府定期推翻了平房,让他们的居民在露天之下生活。

Ironically, the organic geometry of the favela is typically at odds with the imperatives of both the Left and the Right in a modern state, given its interest in responding to social issues in a manner that is appropriately controlled. Some of that interest in control has to do with a literal interest in the kind of rational administrative order that is tied to social control. Nevertheless, much of it may reflect either the state’s need to legitimate its interventions by demonstrating its rationality, or its need to maintain the bureaucratic rituals of accountability when distributing public resources, or its respect for the conventions of private property. It could also be a sincere reformist concern for elevating the living standards of the poor in a way that is both efficient and procedurally fair, in a manner motivated by democratic principles.

An ordered geometry gives the impression of control invested in the entity that builds. Whether this is intentional (to display the authority of the state) or subconscious (copying images from architecture books), governments and non-governmental organizations prefer to see such an expression of their own “rationality” through building. Departure from this set of typologies is felt to be a relaxation of authority; or it raises possible questions regarding the legitimacy of distributions of resources that aren’t subject to careful bureaucratic accounting procedures.

Both of these are avoided because they tend to erode the authority of the state, particularly under regimes where the rights of private property are an important part of the legal and regulatory systems. Morphologically complex squatter settlements are usually outside the government’s control altogether. One way of asserting control is to move their residents to housing built by the government. In a sad and catastrophic confirmation of our ideas, various governments in Africa have periodically bulldozed owner-built dwellings, driving their residents to live out in the open.

下一章摘要

在下一篇中,我们将进一步描述当下的设计和施工过程、政治和非政府机构参与规划过程和改造贫民窟的细节。我们还将描述一个明确关于在绿地或开放的棕地上建立廉租房的理念。

本文非常复杂,涉及很多问题,因此我们需要一一论述。第1节提供背景并批评当前的做法。第2节将回顾了自上而下的社会住房计划的标准做法和类型,并建议用自下而上的程序取代它们(或至少补充它们)。第3节指出了政府的“几何控制”使平房区变得不人道,并破坏了其建筑肌理。

之后的内容将提到了特定的设计工具。第4节描述了建筑环境建立情感联系的机制。 “Biophilia”,也就是说建筑直接连接到植物生命的需要,是一个至关重要的组成部分。我们还讨论了宗教空间及其在建立社区方面的作用。第5节回顾了Christopher Alexander的作品,特别是他最近关于生成模式的著作。第6节反对固定的总体规划方法,建议采用迭代的规划过程。第7节回顾了Christopher Alexander模式,并概述了其向生成代码的过渡。第8节以最广泛的术语给出规划的解决方法。我们建议获得实践许可,而不是纸上谈兵。第9节包含一组明确的模式,用于生成社会住房项目中的服务中枢。第10节通过描述这样一个项目所需的模式来介绍补充设计工具。

Summary of subsequent essays

In subsequent essays, we will develop the present methodology further to describe the design and construction process; the involvement of political and non-governmental agencies in planning; and details for retrofitting favelas. We will also include an explicit generative sequence for building social housing on a greenfield or open brownfield.

This paper is very complex and deals with many issues, so we need to map out its exposition. The first sections provide background and criticize current practices. Section 2 reviews the standard practices and typologies of top-down social housing programs, and recommends replacing them (or at least complementing them) with a bottom-up procedure. Section 3 pinpoints how a “geometry of control” ruins even the best-intentioned schemes by making them inhuman.

The next sections offer specific tools for design. Section 4 turns to mechanisms for establishing emotional connections with the built environment. Biophilia, or the need to connect directly to plant life, is a crucial component. We also discuss sacred spaces and their role towards establishing community. Section 5 reviews the work of Christopher Alexander, especially his recent work on generative codes. Section 6 argues against the fixed master plan approach, suggesting instead an iterative back-and-forth planning process. Section 7 reviews Alexandrine patterns and outlines their transition to generative codes. Section 8 gives, in the broadest possible terms, our methodology for planning a settlement. We suggest getting building permission for a process rather than for a design on paper. Section 9 contains an explicit set of codes describing the armature of services in a social housing project. Section 10 introduces the complementary design tools by describing the generative codes needed for such a project.

第二章即将发表:拉丁美洲社会住房的反模式。

本文最初由N.A.S.为巴西和伊比利亚 - 美洲社会住房大会的主题演讲,位于巴西,Florianópolis,诺波利斯,2006年。

Soon, the second chapter: Antipatterns of Social Housing in Latin America.

Originally presented by N.A.S. as a keynote address to the Brazilian and Ibero-American Congress on Social Housing, Florianópolis, Brazil, 2006.

参考

- Christopher Alexander(2001-2005)秩序的本质:第一至第四册(A Pattern Language,加利福尼亚州伯克利)。

- Christopher Alexander,S。Ishikawa,M。Silverstein,M。Jacobson,I。Fiksdahl-King&S。Angel(1977)A Pattern Language(牛津大学出版社,纽约)。

- Hassan Fathy(1973)Architecture for the Poor(芝加哥大学出版社,芝加哥,伊利诺伊州)。

- N。J. Habraken(1972)Supports: an Alternative to Mass Housing(城市国际出版社,伦敦和孟买)。

- Jane Jacobs(1961)“美国大城市的生与死”(Vintage Books,纽约)。

- John F. C. Turner(1976)Housing by People(Marion Boyars,伦敦)。

References

- Christopher Alexander (2001-2005) The Nature of Order: Books One to Four (Center for Environmental Structure, Berkeley, California).

- Christopher Alexander, S. Ishikawa, M. Silverstein, M. Jacobson, I. Fiksdahl-King & S. Angel (1977) A Pattern Language (Oxford University Press, New York).

- Hassan Fathy (1973) Architecture for the Poor (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois).

- N. J. Habraken (1972) Supports: an Alternative to Mass Housing (Urban International Press, London & Mumbai).

- Jane Jacobs (1961) The Death and Life of Great American Cities (Vintage Books, New York).

- John F. C. Turner (1976) Housing by People (Marion Boyars, London).

|

|