What We Can Learn About Public Space From Cuba

由专筑网李韧,王雪纯编译

本文最初发表于“CommonEdge”,标题为“景观设计师与城市设计师能从古巴公共空间学习到什么。”

我来到这里的目的,是坐在宽阔的鹅卵石台阶上,看着人们在公共场所玩耍互动。在古巴8月的一天下午,我在一排树下休憩,我作为一名景观设计师,工作主要面向城市公园、街道、校园等等,因此我想观察古巴的开放空间。

这些场景让我想起著名的城市规划者、理论家凯文·林奇,他的《城市意象》一书对后人产生了重大的影响。在五十年前某个充满阳光的午后,那是我第一次开始管理项目,所以我查阅了很多前辈们留下的资料。在凯文·林奇生命的最后时光里,他把各种草稿、草图、速写都赠与麻省理工学院,它们现在都保还留在档案馆中。我的老板是Richard Burck Associates的负责人,他对凯文·林奇的城市感知理论和景观设计十分感兴趣。因此,我的任务便是查遍林奇档案的每一页,然后不断地记录下各种信息。

在8号盒子里有一些照片,地点与摄影师都不得而知,但是图像的意义十分明确。其中有两种人物形态,即工人、大学生,或是酒鬼,他们躺在小岛上,周围是树木与草坪。图像很明确,表达的就是遮阳的人们,这张图像很清晰地印在了我的脑中。

This article was originally published on CommonEdge as "What Landscape Architects and Urban Designers Can Learn About Public Space From Cuba."

It was certainly what I had come for: I was sitting on broad, cobbled steps, watching people interact in the public realm. It was an August afternoon in Cuba, and I had found temporary respite from the harsh sun beneath a haphazard array of trees. My design work as a landscape architect focuses on urban parks, streetscapes, and academic campuses, and I wanted to see how differently the open spaces of Cuba might function.

Something about the scene immediately reminded me of Kevin Lynch, the great urban planner and theorist best known for his influential 1960 book, The Image of the City. A half-decade before that sun-drenched afternoon, I was just starting to manage projects for the first time, so it seemed like a diversion to be rummaging through the contents of a dead man’s filing cabinet. At the end of his life, Lynch’s various manuscripts, papers, and sketches were bequeathed to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where they are now housed in an archive. My boss, principal of Richard Burck Associates, was interested in Lynch’s theories of urban perception and how they might overlap with the legacies of landscape design. As a result, I was tasked with flipping through nearly every page of the Lynch archives, taking notes, and filling out a multitude of reproduction-request forms.

One loose photograph in Box #8 stood out. Neither the location nor the photographer is documented, but the significance of the image leaps from the print. Two human forms—perhaps day laborers, college students, or drunks—lie supine in the small island of shade cast by a young tree in an otherwise open lawn. Reading as clearly as a diagram, the image captures landscape inhabitants seeking refuge from the beating sun, and the clarity of this snapshot lodged itself in my mind.

在2016年的夏天,我来到古巴哈瓦那,这里是俄罗斯导弹和美国经典汽车的发源地,二战时期曾经禁止运送货物,禁止人出境。我当时第一次来到古巴,逐步意识到自己脑子里的文化压力,但是这种压力很快就消散了。从入境以来,我并未感受到冷漠,古巴人的真诚让人感觉很温暖。

10天以来,我穿梭在风景线之中,以各种方式游览这个城市,步行、公共汽车、出租车等等,我逐渐感受了古巴的当地特征,这些场所色彩情感都很丰富。旅行中,我经过Matanzas省、Clara别墅、Sancti Spiritus、Cienfuegos、 La Habana,在这里我看到了城市与乡村、海滩与田地、山脉与天空,街道两侧混杂着现代与殖民建筑。

在我旅行那段时间内,美国公民享受着短暂的假期,因此,我们可以在古巴进行自由研究旅行,但是仍然需要一些官方文件。因此,我在这里进行着“全方位公园与公共广场的古巴式景观设计策略的研究”,当我漫步在烈日下,我花了好几个小时来观察古巴的街道、广场、廊道的设计方式。大约在某天的中午,我突然有些领悟。

Then, in the summer of 2016, I arrived in Havana, Cuba. Land of Russian missiles and classic American cars. Cold wars and cold shoulders. An embargo of goods and of people, consequently, frozen in time. As an estadounidense entering Cuba for the first time, I became aware of the cultural baggage I was carrying and quickly saw it slough off. From the immigration desk forward, I did not encounter a trace of this forewarned coldness. Cuba was all warmth in its sincerity of smiles and the height of its mercury.

For 10 days I followed the scenic loop I had plotted through the island’s countryside villages, traveling by foot, bus, modern taxi, and, of course, Cuba’s famed almendrones, which were just as muscular, colorful, and bondo-ed together as my guidebook had promised. The trip was by no means long enough, but across the provinces of Matanzas, Villa Clara, Sancti Spiritus, Cienfuegos, and La Habana I was able to see urban and rural; beaches, farm fields, and mountains; and streets flanked with a contradiction of modern buildings and famed colonial architecture.

At the time I traveled, U.S. citizens were enjoying a brief window during which we were permitted to conduct self-guided research trips to Cuba, but the preparation of certain bureaucratic paperwork was technically required. Ostensibly, I was in the country to “research, on a full-time basis, unique Cuban approaches to landscape architectural design of parks and public squares.” As I sweat through my new guayabera, this notarized statement I kept on my person was not far from the truth. I spent hours observing the many ways in which Cuba’s streets, squares, and promenades were being used. Around noon one day, I had an embarrassingly late epiphany under the blazing sun.

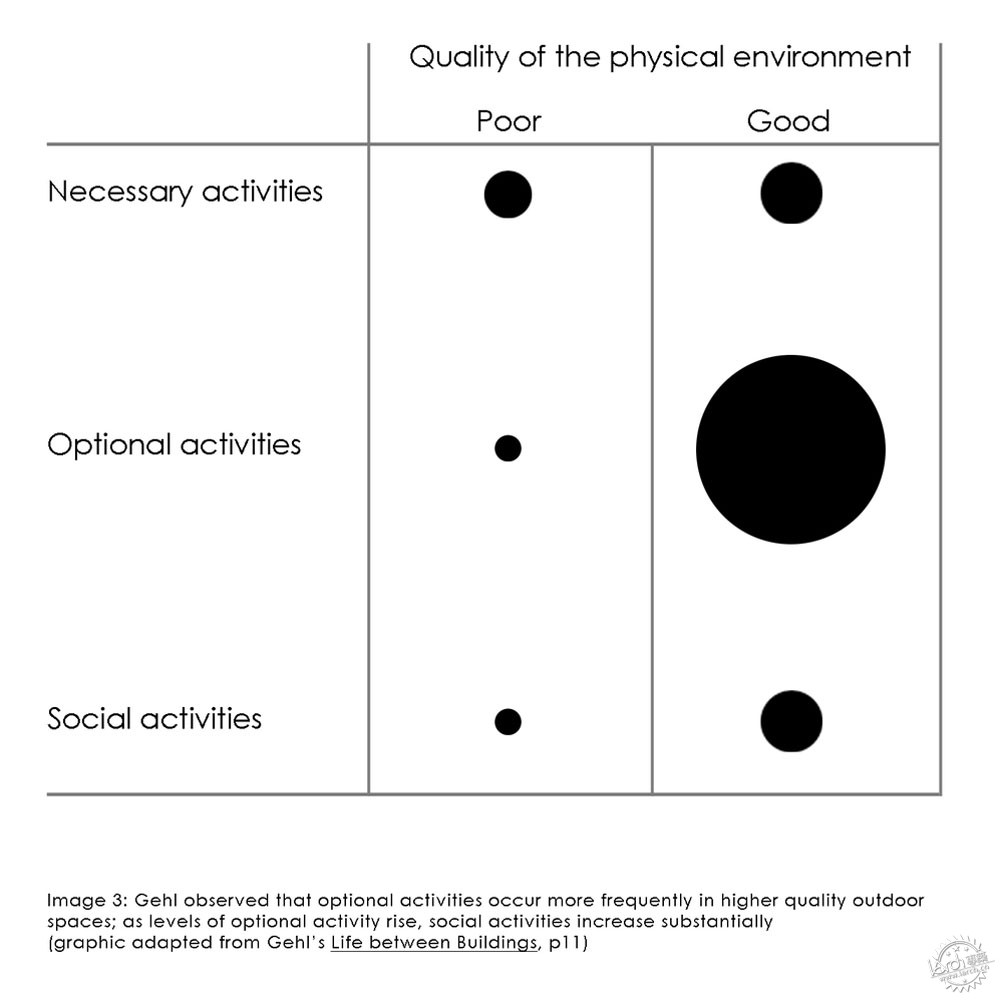

城市理论家Jan Gehl在《建筑之间的生活》的第一章节就将所有人们的室外活动分为了三个类别,即“必要活动、可选活动,以及社交活动。”必要活动室指人们上班、上学所必要的通勤日常,亦或是寄快递等目的性任务地点,可选活动的意思是步行或跑步,人们“享受生活,或是坐着享受日光浴,”这类事项发生在特定的天气、地点之中,而社交活动则建立在二者的基础之上,其中有“儿童玩耍、人们交谈、社区聚会,亦或是单纯地旁观。”

Urban theorist Jan Gehl, in his first chapter of Life Between Buildings, streamlines all human outdoor activity into three categories: “necessary activities, optional activities, and social activities.” Necessary activities include pedestrians’ requisite commutes to work and school, delivering mail and packages, and point-to-point errands. Optional activities, which include walking or jogging for exercise, “standing around enjoying life, or sitting and sunbathing,” occur only when “weather and place invite” people to perform them. Social activities, which build upon the presence of other people partaking in the necessary and the optional, include “children at play, greetings and conversations, communal activities … [and] the most widespread social activity … simply seeing and hearing other people.”

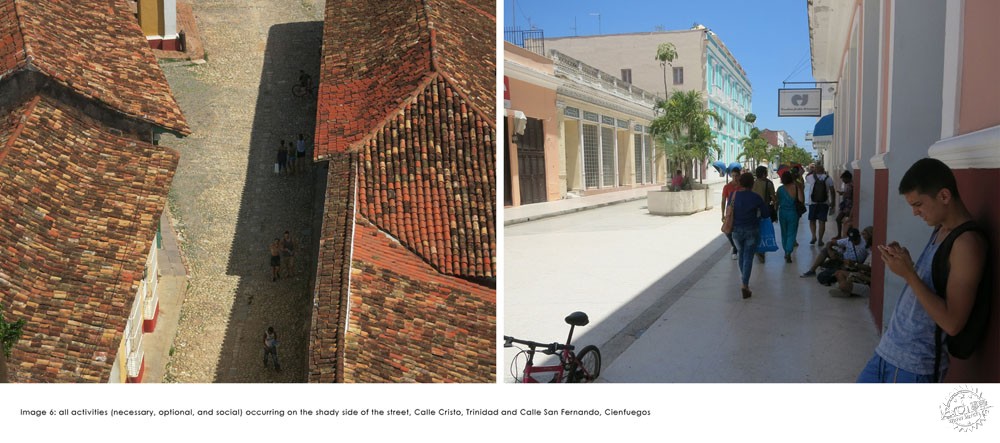

古巴烈日当头,开放的空间中承载了Gehl所描述的各项活动。在Trinidad镇上的一个中午,游客们都在Mayor广场的边缘行走,这里单层殖民建筑为他们遮挡了烈日,他们就于这块阴凉处进行各项活动。几个小时之后,太阳向西边走了一些,于是这一片的阴影区就不见了,因此广场上的人也少了一些,他们都去往了树荫底下。

With a hard Cuban sun overhead, the open spaces sorted out Gehl’s activities like a sieve before my eyes. At midday in the town of Trinidad, visitors lounged together on the edges of Plaza Mayor, participating in a mixture of optional and social activities on a tall curb shaded by a single-story colonial building. Hours later, with the sun a bit to the west, the sliver of shade had disappeared, and the same piece of plaza had become inhospitable. Now the only people to be seen were in the distance, bunched beneath the shady sanctuary of trees.

如果通过图像来表达Mayor广场的日光,那么可以明显看出,由于阳光的照射,场地东北侧地区会逐渐变得热闹与有趣。广场向上倾斜,看起来有点像罗马的西班牙大台阶,一些树木种植在鹅卵石台阶上,这个画面我在文章一开始就描述过。在这里,人们慵懒地玩着手机,从图上可以看出来,树木投影所形成的区域就好像有免费WIFI一样吸引着大众。

While Plaza Mayor was tracing a simple diagram of comfort vs. discomfort due to solar exposure, things got even more interesting in the northeast corner. The surface of the plaza turns uphill, reminiscent of Rome’s Spanish Steps, and a half-dozen trees sprawl benevolently over the cobbled terraces, the place I described in my opening sentences. Here, people were hunkered over their phones in something of an organic Venn diagram, drawn where the visible outline of the trees’ shadows overlapped with the invisible radius of a public WiFi hub.

当行人沿着城市街道行走时,道路的设计就存在着规则。无论是曼哈顿还是墨尔本,一些无意识的设计策略让人们能够自行沿着街道行走。这些街道我已经经历了10年,但是在Havana却不同,我在人行道上看到了大汗淋漓的人们。

我没有很深刻地去了解人们行为的逻辑性,但是当地人很有耐心。我之前感受到的那种微妙却深刻的感受,是在炎热的天气下,人们的流动性会更大一些,换句话说,古巴的人行道似乎遵循着这样的规则,“请靠右行走,但烈日当头时除外。”

When a person walks along an urban streetscape, there are tacit rules of the road. The orientation may be flipped from Manhattan to Melbourne, but these unwritten—and often unconscious—regulations enable masses of strangers to move in (relatively) smooth currents along streets and sidewalks. As an urbanist, I have been cognizant of them for a decade, and yet there I was, bumping into pedestrians on the sidewalks of Havana, feeling like a fish out of water.

Despite my failure to pick up promptly on the local logic of human movement, the habaneros were patient. For a time I was left with a subtle but deep-seated unease, but once I learned my lesson it stuck: extreme sun exposure calls for an improvisation of pedestrian flows. To put it more bluntly, Cuba’s unwritten sidewalk rule is as follows: “always keep to your right … unless the sun is too hot.”

Gehl明确地指出,可选活动、社交活动与环境质量息息相关,而我看到的是在高温环境下,即使是必要活动,即使需要步行很久,人们也会选择在阴凉地点进行。

小时候我在佐治亚州生活,我大概有一些印象,“聪明的小狗会躲在树荫下乘凉”。我并没有忘记这个概念,其实我所分享的内容都只是人类的常识和本能反应。太阳对于人们的生活有着重要的作用,但是在建筑设计等过程中,是否有过于强烈的阳光则是必要的考虑要素。

全世界的人大概都听说过极权主义政府,但是古巴的公共空间似乎没有那么多约束,这里会更加灵活一些。不那么正式的公共空间和半私人的场所有时可以混合交杂,与低速的步行街道相结合,服务于城市中心,提供活跃且自由的各项活动场地。

While Gehl makes clear that optional and social activities are dictated by environmental quality, what I saw was extreme heat and glare diverting even the necessary pedestrian travel into the shade, even when it required a pedestrian to take a longer route with extraneous street crossings.

From my childhood in Georgia, I can only fuzzily recall some idiom about “even dogs being smart enough to sit in the shade.” It is not lost on me that all of the observations I am sharing here could be labeled common sense. However, despite the clear influence that the sun has on human comfort, solar-exposure analysis all too often comes as an afterthought to grand pattern-making, architectural expression, and materiality.

In spite of the totalitarian government the world hears so much about, the Cuban public spaces I observed appeared less prescriptive, more flexible, and—unless it was all a complex ruse—far more democratic than the majority of parks and streetscapes in the U.S. There was an informal and imperceptible blending of public ways to semiprivate stoops that, coupled with low-speed, pedestrian-prioritized streets, made for socially active, flexible urban centers.

公共空间的设计不仅要呼应使用者,也要呼应大自然。人们可以在宽敞、灵活、多样的景观之中寻找遮阳场所,当然如果是在冬天的波士顿,人们就需要寻找阳光,因此这些空间对于人们来说非常重要。阳光决定了公共开放空间是否成功,如果城市规划者、建筑师、景观设计师忽略了阳光,那么一定会造成相应的后果。这就像凯文·林奇那张照片一样,我在古巴学到的东西深深刻在我的脑海中,并且和实际作品相结合,阳光与人类不可逃避,更不可分割。

图片:Sam Valentine

The design of the public realm should respond not only to people and not only to nature. Broad, flexible, and varied landscapes preserve the ability of pedestrians to informally drift and seek shade (or, as in Boston during the winter, seek sun), and this is critical to the casual lingering of users. The sun all but determines the success of an open space, and when urban planners, architects, and landscape architects ignore its impacts, they do so at their own peril. Like Lynch’s striking photo, the lessons I learned in Cuba have burned into my memory and carried into my professional practice: The link between the sun and the humans who depend on it is undeniable and inescapable.

|

|