卢森堡爱乐音乐厅|Luxembourg Philharmonie, Luxembourg, 2005. Image © Wade Zimmerman

克里斯蒂安•德•包赞巴克:只有建筑师能解决当代城市问题

Christian de Portzamparc: “No One But an Architect Can Solve the Problems of the Contemporary City”

由专筑网邢子,韩平编译

在普利兹克奖获奖者名单中,1994年的得主克里斯蒂安•德•包赞巴克可能是媒体报道最少的。 然而,这种相对较低的曝光机会掩盖了他对建筑和城市问题的微妙关系的洞察力和理解,他几十年前提出的曲线 ——自20世纪80年代初以来一直在发展的社会主义原则,现在在建筑界广受欢迎。在最新的Vladimir Belogolovsky的“思想城市”专栏,包赞巴克解释了导致这种独特的建筑风格的思想过程。

Of the Pritzker Prize’s illustrious list of laureates, the 1994 winner Christian de Portzamparc is perhaps the least covered by the media. However, this relatively low profile belies the subtle and insightful understanding of architectural and urban issues that in many ways puts him decades ahead of the curve – with the sociologically-led principles he has been developing since the early 1980s now becoming widely popular in architectural circles. In this interview, the latest in Vladimir Belogolovsky’s “City of Ideas” column, Portzamparc explains the journey that led to this unique take on architecture.

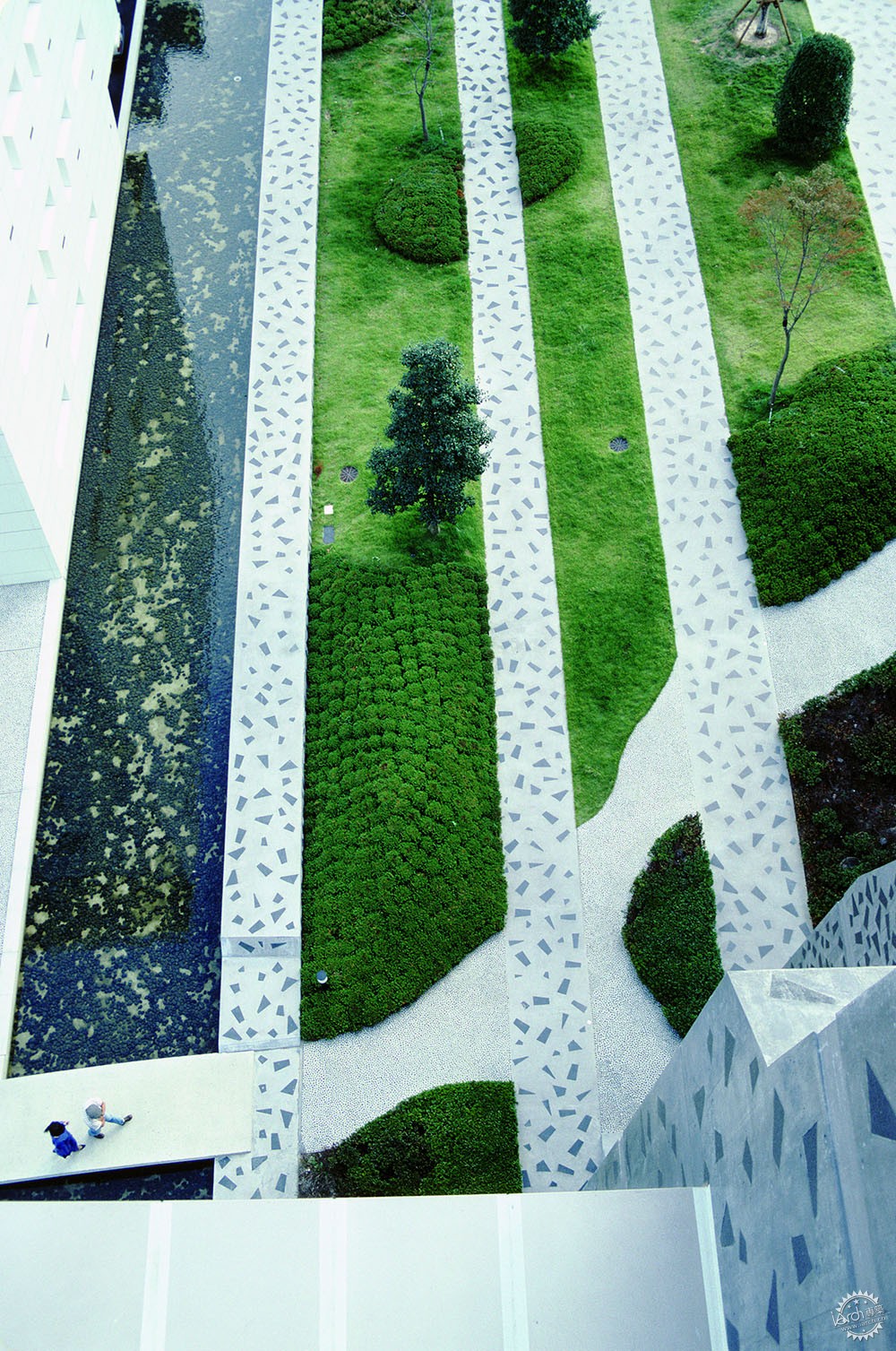

苏州文化中心|Suzhou Cultural Center Proposal, Suzhou, 2017. Image © Christian de Portzamparc

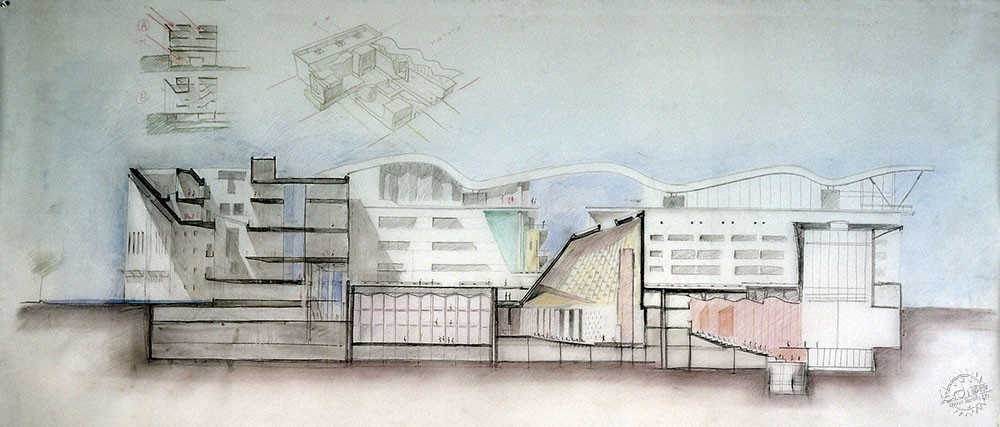

Christian de Portzamparc:...建筑设计过程中经常出现有争议的事情,比如绘画。 在六,七十年代,我们绘图。后来我去了巴黎的美术学院,绘画就结束了。 但在现代教学中绘画被认为是不重要的,建筑会被绘画所影响。 我一边思考和一边勾画草图。 事实上,绘画可能会在一个特定的想法发生之前就开始了。

Christian de Portzamparc: …Architecture often comes out of a controversial matter, drawing. In the 60s and 70s, we were contesting the drawing. I went to the Beaux-Arts school here in Paris, in which drawing was an end in itself. But in the Modern teaching to draw was viewed as dangerous, meaning to be absorbed and seduced by the quality of the drawing itself. I was thinking and drawing at the same time. In fact, a drawing may come before a particular imaginative idea sparks.

Vladimir Belogolovsky:这对你来说是一个潜意识的过程。

CP:也许...它不一定与思考和表达有关...

Vladimir Belogolovsky: A drawing to you is a subconscious process.

CP: Maybe… It is not necessarily associated with thinking and explaining…

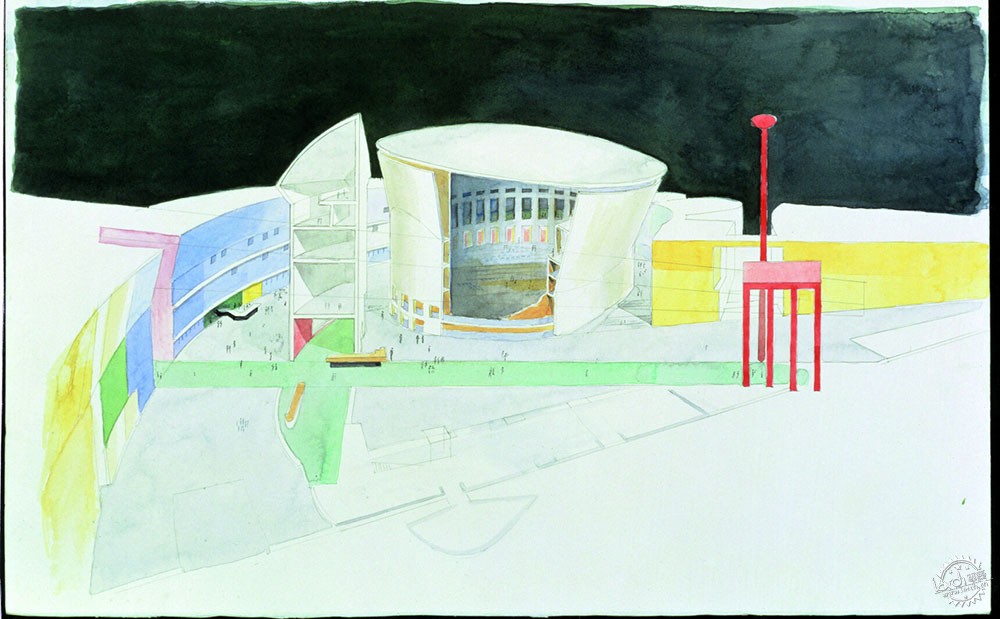

巴黎音乐城|Cite de la Musique West Wing, Paris, 1990. Image © Christian de Portzamparc

VB:从设计到项目的工作是否有连续性? 你这样认为吗?

CP:当然 我总是被新的东西所吸引,我不断关注我感兴趣的事情。 当我从事新项目工作时,我经常意识到我正在解决一个我五年或十年前想解决的问题。 一些想法或问题一次又一次地出现。

VB: Is there continuity in your work from project to project? Do you see it that way?

CP: Sure. I am always attracted to something new but I think about things that interest me continuously. And when I work on new projects I often realize that I am solving a problem which I tried to resolve five or ten years before. Certain ideas or formal relationships come up again and again.

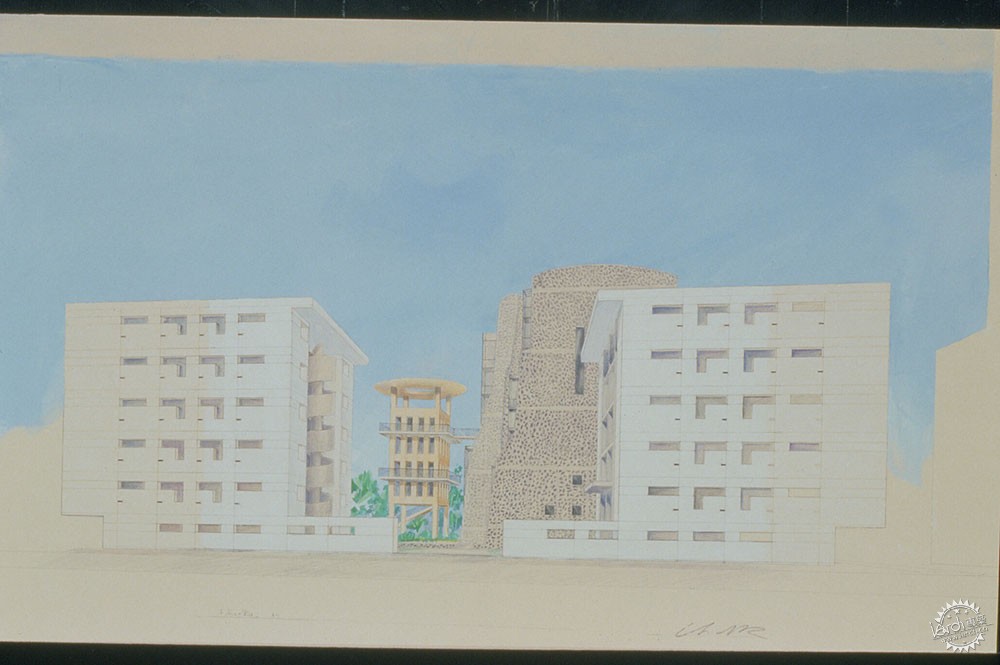

巴黎歌剧院舞蹈学校|Paris Opera Ballet School, Nanterre, 1987. Image © Atelier Christian de Portzamparc

VB:什么引发了您对建筑最初的热情?

CP:当我15岁的时候,我发现了勒柯布西耶的绘画和建筑。 他的绘画和昌迪加尔的形象给我一个最初的印象。 在此之前,我画图,但是我并没有意识到绘图的内容可能是一个地方,一幅绘画可能会变成真实的东西,是人们可以生活或工作的东西。 所以我也被城市迷住了。 在布列塔尼的雷恩市周围,我住的地方,我看到新的、白色的、理性的建筑作为一个城市的新概念表达,他们就像一个反对旧概念的军队。 就像柯里西耶1922年提出的“La ville sans lieu”,这个字面上翻译为“没有空间的城市”。

VB: What sparked your initial interest in architecture?

CP: Well, when I was 15, I discovered drawings and projects by Le Corbusier. His Open Hand drawing and images of Chandigarh made an impression on me. I was drawing and painting before that, but I did not realize that a drawing could be a place, that a drawing could become something real; something in which people can live or work. I was also fascinated by the city. Around the city of Rennes in Brittany where I was living, I saw new, white, rational buildings arriving as a new concept of a city; they were like an army fighting against the old concept. There was a clash of old and new, like Le Corbusier’s famous 1922 proposal “La ville sans lieu” for three million inhabitants, which literally translates as “The city without place.”

迪奥首尔旗舰店|Flagship Dior, Seoul, 2015. Image © Nicolas Borel

VB:你是否反对这个与众不同的想法?

CP:不是。 在1966年,当我住在纽约,后来当我和社会学家一起工作时,我开始研究居民对这些城市变化的反应。

VB:我了解到,在20世纪60年代,你有兴趣发现新的社区和序列的想法,以及城市和电影之间的关系——城市是“情景”。你能谈谈吗?

CP:回到纽约以前,我对新的完美城市的想法感到兴奋,但我意识到,构想未来不一定是擦除过去,这是勒柯布西耶的座右铭。 在Jean-Luc Godard和Michelangelo Antonioni的影片中,我发现了一个真实现代城市的形象:摄像机记录从理想化的米兰和巴黎开始,一直到郊区转和历史街区。 六十年代,在巴黎,城市规则是扩大道路,适应汽车,并为新房创造空间。 传统的街道受到攻击,但这些街道已经有数千年的历史了,比我们更强大。

VB: Did you revolt against this radically new vision?

CP: Not at all, not then. It was only in 1966 when I was living in New York and later when I worked with sociologists that I started learning about the inhabitants’ reactions to all these urban changes.

VB: I read that in the 1960s you were interested in inventing new neighborhoods and the idea of sequences, as well as the relationship between the city and the film – the city as “scenario.” Could you talk about that?

CP: Going back to before the time I was living in New York, I was excited about the ideas for new, perfect cities but I realized that imagining the future is not necessarily about erasing the past, which was the motto of Le Corbusier. In the films by Jean-Luc Godard and Michelangelo Antonioni from this period I found an image of the real modern city: the camera was moving from the idealized, perfectly geometric suburbs of Milan and Paris, towards historical neighborhoods and back. In the 60s, here in Paris the urban rules were to widen the roads to adapt to the automobile and to clear space for new housing. The traditional street was under attack, but the idea of the street has been around for thousands of years and it is more powerful than we are.

巴西Cidade Das Artes艺术馆|Cidade das Artes, Rio de Janeiro, 2013. Image © Nelson Kon

VB:大概在1966年左右,你开始觉得“独一无二的建筑与城市的现实生活是无关的”。而在1967年,你甚至决定完全退出建筑。 你当时只有23岁.发生了什么事,什么让你选择继续从事建筑?

CP:1966年我在纽约呆了一年。在那里,我参与了绘画,音乐,戏剧,阅读等艺术,我在考虑成为一个画家或作家。 当时我想体验很多的可能性。 我本应该在建筑事务所工作,会见保罗•鲁道夫和爱德华•拉拉比•巴恩斯,但是我改为选择在第57街工作兼职作为调酒师,比我在办公室做一个绘图员可以赚到更多的钱, 我就可以享受这个城市,遇见很多人。 我不再相信我会是一位建筑师。 我对建筑的兴趣通过我对政治和社会学的兴趣而被重新启发,关注在拥挤的社区和幽闭公寓中不开心的人们。 我从来没有停止把空间视为一种艺术媒介。 除建筑师外,别人也不能解决当代城市的问题。

VB: Around 1966 you began to feel that “architecture alone was dry and unrelated to real life in the city.” And in 1967 you even decided to quit architecture altogether. You were just 23. What happened and what made you stay with architecture?

CP: I was in New York for a year in 1966. There I was, involved in artistic life such as painting, music, theater, reading, and I was thinking about becoming either a painter or a writer. It was the time when I wanted to experience many possibilities. I was supposed to work in an architectural office, meetPaul Rudolph and Edward Larrabee Barnes, but then instead I chose to work part-time as a bartender on 57th Street, making more money than I could possibly make as a draftsman at an office, so I could enjoy the city and meet many people. I stopped believing that I would be an architect. My interest in architecture was reignited through my interest in politics and sociology, concern for people who were not happy in their crowded neighborhoods and claustrophobic apartments. And I never stopped perceiving space as an artistic medium. I understood that no one else but an architect could solve the problems of the contemporary city.

巴西Cidade Das Artes艺术馆|Cidade das Artes, Rio de Janeiro, 2013. Image © Nelson Kon

VB:你明白建筑不仅仅是一个对象。

CP:恰恰相反,但不止于此。 当我1965年来纽约时,我的印象是建筑师已经过时了。 我认为未来的城市将由社会学家和电脑设计。 房屋将组装在工厂,人们会购买他们喜欢的东西,社会学家将组装它们。 那你为什么要建筑师呢? 这一切都将像一个生活过程一样,就像Archigram和代理人所设想的一样。 这就是为什么我对建筑失去兴趣。 我不想成为组装这些插件城市的工程师。 然后,通过在法国的新城市发展和访问新城市,我意识到空间是一个观念的问题,这与概念艺术不同,这也是我的兴趣。 我明白,在街道消失的新世界和汽车无处不在的地方,空间的想法至关重要,人们现在感到迷失了。

VB: You understood that architecture could be more than just an object.

CP: Exactly, but more than that. When I came to New York in 1965, I was under the impression that architects were obsolete. I thought the city of the future would be designed by sociologists and computers. Houses would be assembled in factories, people would buy what they like, and sociologists would assemble them. Why would you need architects then? It would all become like a living process, just as Archigram and the Metabolists envisioned. That’s why I was losing interest in architecture. I didn’t want to become an engineer to assemble these plug-in cities. Then by working on new urban developments in France, and visiting new cities, I realized that space is a problem of perception, which is not far from conceptual art that was also my interest. I understood that the idea of space is crucial in the new world where the street has vanished and cars are everywhere, and people now feel lost.

巴黎音乐城|Cite de la Musique West Wing, Paris, 1990. Image © Nicolas Borel

巴黎音乐城|Cite de la Musique West Wing, Paris, 1990. Image © Nicolas Borel

巴黎音乐城|Cite de la Musique West Wing, Paris, 1990. Image © Nicolas Borel

VB:当你在1994年获得普利兹克奖时,陪审团引用说:“每一个渴望伟大的建筑师必须在某种意义上重构建筑。”这是你尝试做的吗? 你的工作是关于改造还是更微妙?

CP:我记得从1966年到1971年,我还在寻找并不断地提出这个问题 ——什么是建筑? 而且我以为一位不问这个问题的建筑师不是一个有趣的建筑师。 你必须明白为什么做你所做的事情,它有多么有用。 是什么让你在艺术或社会学上充满热情? 一旦你明白了,你就有机会被其他人理解。 我想我在七十年代初理解为什么我想做这个项目,以哪个方式。 但重新创造是一个非常自负的立场。 相反,我们通过几代人和思想之间的激烈对话来重现事物。 让建筑再次开始。

VB: When you won the Pritzker Prize in 1994 the Jury citation said, “Every architect who aspires to greatness must in some sense reinvent architecture.” Is that something that you try to do? Is your work about reinvention or is it more subtle?

CP: I remember that from 1966 to 1971, I was still searching and constantly asking this question – what is architecture for? And I thought that an architect who is not asking this question is not an interesting architect. You have to understand why you do what you do and how useful it is. What is it that makes you passionate artistically or sociologically? Once you understand this, you have a chance to be understood by others. I think I understood in the early 70s why I would want to do this project and which way. But reinventing is a very pretentious position. Instead, we recreate things through an intense dialogue between generations and ideas. We start again.

巴黎欧风路(RUE DES HAUTES-FORMES)209户住宅设计|Les Hautes Formes Housing, Paris, 1979. Image © Nicolas Borel

VB:你会说你觉得有能力带来另一个愿景,这是一个个人的立场?

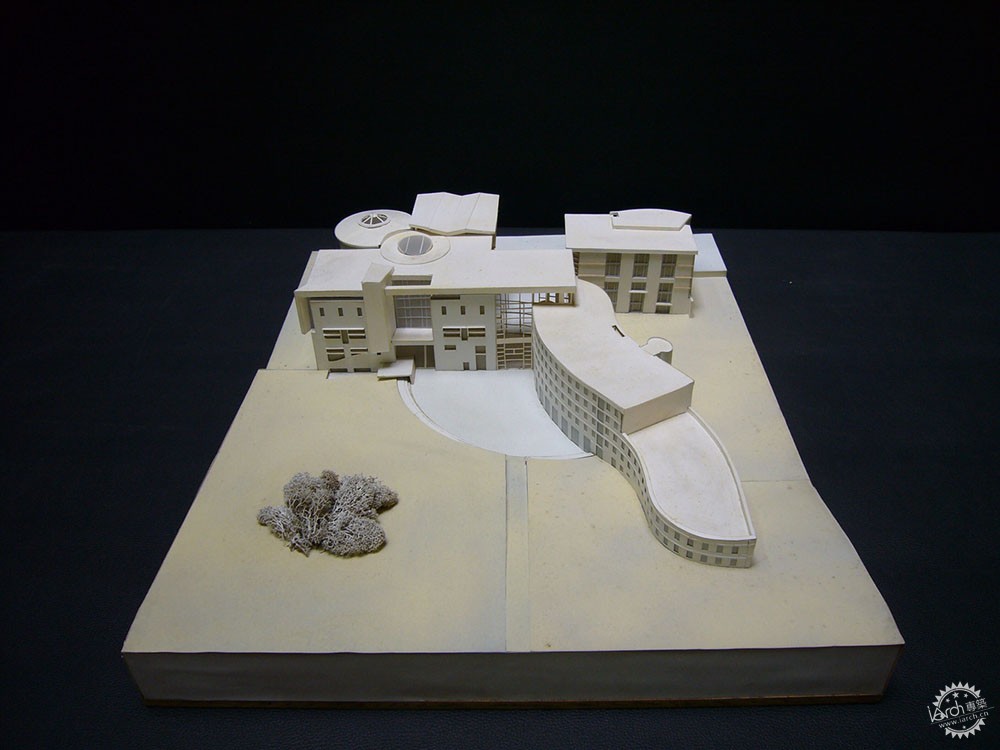

CP:是的 我当时没想到我会有个人的愿景,但是我以为我有一个愿景,如何让空间感觉到,在新的发展中失去了一些东西; 我们如何能够整合新的与旧的,我们如何可以改善现有的城市。 在过去,建筑成为一种单一建筑的形式,这些建筑物如何沿着街道和广场周围排列。 1975年,在我在Rue des Hautes Formes的一个住宅区的竞赛项目中,没有像我的竞争对手那样提出一个建筑,而是提出了七个。 他们计划围绕一个被组织成走道和小广场的空间。 其实我一直认为空间是空的。 老子在他着名的经文中说:“我的家,不是地面,不是墙壁,不是屋顶,是所有这些元素之间的空间,因为它正是我呼吸和我居住的地方。”

VB: Would you say that you felt capable of bringing another vision, a personal stand?

CP: Yes. Well, I did not think then that I had a personal vision, but I thought I had a vision for how to make space perceivable, something lost in new developments; how we could integrate new with old, how we could improve the existing city. In the past, architecture succeeded as far as a form of a singular building and how these buildings would line up along the street and around the plaza. In 1975, in my competition project for a residential complex on Rue des Hautes Formes I proposed not one building, as my competitors did, but seven. They were planned around a void that was organized into walkways and small plazas. In fact, I always thought of space as void. In his famous verse Lao Tseu said, “My home – it is not the ground. It is not the walls. It is not the roof. It is the void between all these elements because it is exactly where I breathe and what I inhabit.”

巴黎欧风路(RUE DES HAUTES-FORMES)209户住宅设计|Les Hautes Formes Housing, Paris, 1979. Image © Christian de Portzamparc

VB:换句话说,一个空间不仅仅是一个限定,更是经验。

CP:当然,敏感性和传统价值观很重要。 但是对于现代主义者来说,建筑就是一个tabula rasa。现代主义对于柯布西耶,就像基督教对于圣保罗。 以前不被容忍的事情出现了,我意识到,如果我们继承这个20世纪这个艺术旗帜词“现代”,它的意义就会消失。 这句话与Apollinaire在一个世纪前宣布的一样:“我从来不想停止对机车的惊讶”。我们不能拥有与柯布西耶所说的相同的基本经验:“我们是历史上的第一位看到机器的人“,”现代“一词的意思必须重新发明,现代主义是现存的一个中断,我们生活在一个不断变化的时代,尝试项目的重新发明,我相信,最好的项目就是重塑人们对未来的信心。

VB: In other words, a void is not a mere definition, but experience.

CP: Sure, and sensitivities, and traditional values are important. But to Modernists, architecture was a tabula rasa. Modernism to Le Corbusier was like Christianity to Saint Paul. There was no tolerance for anything that was existing before. I realized that if we have inherited this word "Modern," the artistic banner of the 20th century, its meaning is lost. This word cannot have the same meaning now as when Apollinaire declared one century ago, "I never want to stop being amazed by the locomotive.” We cannot have the same basic experience that Le Corbusier had when asserting: “We, the first in history, saw the machine.” The meaning of the word "Modern" has to be reinvented. Modernism is a disruption in something existing and we live in an era of constant change and willingly or unwillingly architecture reinvents tomorrow from project to project. I believe that the best projects are about reinventing this confidence in the future.

里昂信贷银行大厦|Credit Lyonnais Tower, Lille, 1995. Image © Nicolas Borel

VB:在你之前的一次采访中,你说过,“看到l个人对集体主义的表达的一个根本的演变”。你现在觉得我们的社会越来越不愿意提倡个性? 你怎样认为建筑师的声音变得越来越不明朗,越来越难以区分,越来越少个性化的事实呢?

CP:提倡个性来自于Andy Warhol这样的艺术家,他用这个讽刺的方式普及了这个观念。 在建筑中,表达个性的愿望始于过去,在现代主义停止,并成为唯一的模式。1978年普利兹克奖的颁发,标志着国际风格的终结,使建筑师成为著作者。

VB: In one of your earlier interviews, you said that you “see a fundamental evolution in which the expression of individuality over collectivism is coming to the fore.” What do you think about this now that our society is less and less willing to celebrate individuality? What do you think about the fact that architects’ voices are becoming less pronounced and more and more indistinguishable and less personalized?

CP: The celebration of the individual came with such artists as Andy Warhol who popularized this notion with his irony. In architecture, the desire to express individuality started in the past, when Modernism stopped being the only model. We may see the inauguration of the Pritzker Prize in 1978, marking the end of International Style. It was meant to celebrate an architect as author.

福冈Nexus II 住房|Nexus II Housing, Fukuoka, 1991. Image © Nicolas Borel

福冈Nexus II 住房|Nexus II Housing, Fukuoka, 1991. Image © Nicolas Borel

福冈Nexus II 住房|Nexus II Housing, Fukuoka, 1991. Image © Christian de Portzamparc

VB:即使在普利兹克之前,文图里还有他的《复杂性和矛盾性》一书,首先在1966年吹捧了这种崇拜宗教信仰的现代主义模式。

CP:是的。普利兹克在20世纪40年代或50年代不可能存在。 当建筑师开始质疑一切时,文图里和普利兹克都在建筑中开创了一个新的时代。 这是一个新的发展方向,与勒柯布西耶或阿尔托的建筑非常不同。

VB: And even before the Pritzker, it was Venturi with his Complexity and Contradiction book that first blew up this model of puritanical, religiously obeyed Modernism back in 1966.

CP: Absolutely. And the Pritzker could not have existed in the 1940s or 50s. Both Venturi and the Pritzker unleashed a new epoch in architecture when architects began questioning everything. It was a new evolutionary turn, very different from the architecture of Le Corbusier or Aalto.

巴黎欧风路(RUE DES HAUTES-FORMES)209户住宅设计|Les Hautes Formes Housing, Paris, 1979. Image © Nicolas Borel

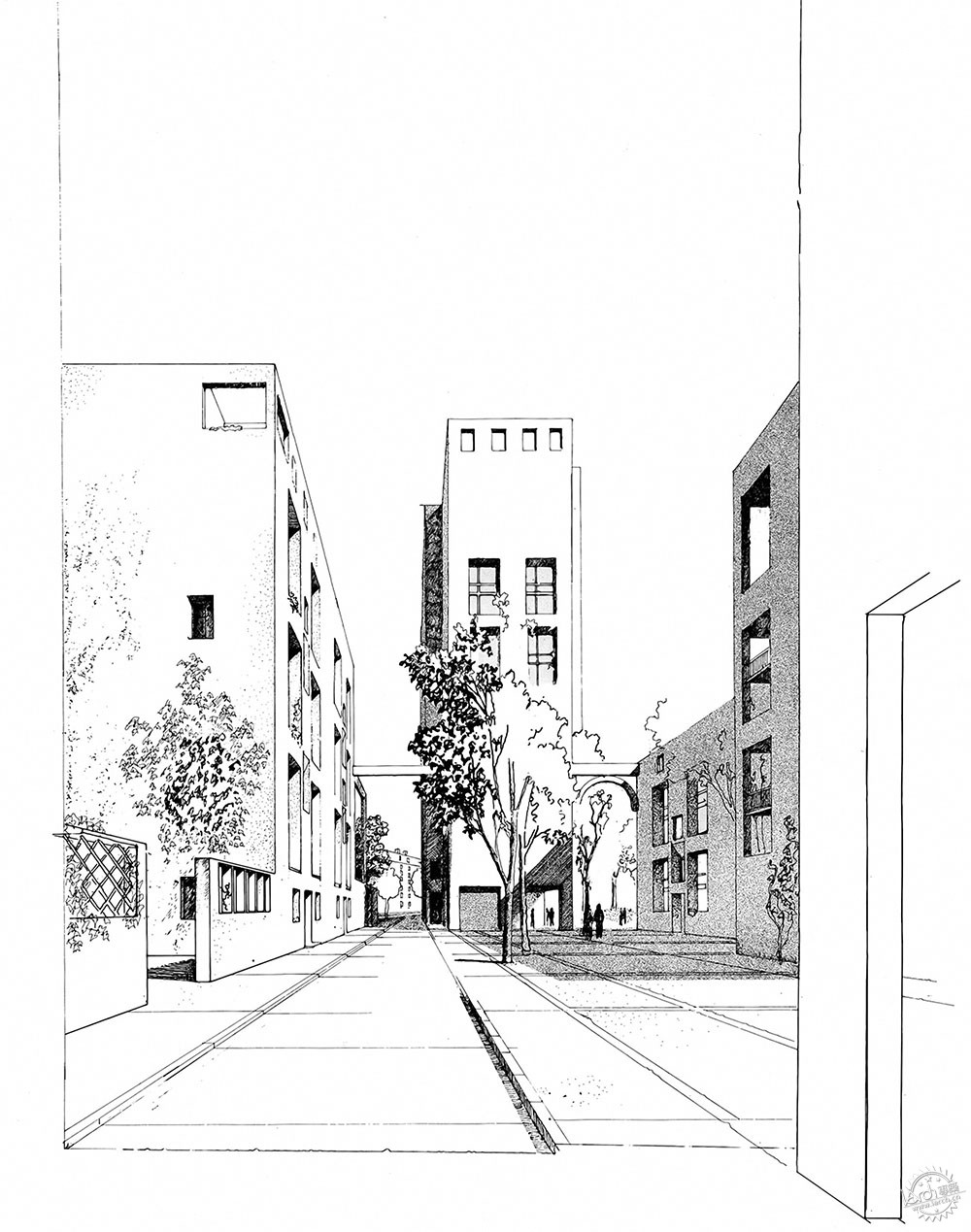

VB:让我们回到Rue des Haute Formes的住宅项目。 这也是你试图摆脱建筑的隐匿性格的尝试吗?

CP:完全正确。我试图提供不同类型的住房与几种不同类型的窗户和阳台。我认为人们在复合体内识别自己的位置很重要。有一个改变我想法的老师乔治•琼斯说,如果你正在设计一个住宅区,你需要为每个人提供完全相同的情况和条件,平等是一个主要的切入点。是的,平等是一个理想主义的概念,但你学习建筑和城市主义,你意识到,通过同等对待事物,平等遗弃一切。你必须提供各种不同品质 - 更多的花园或更多的出入口等等。只有当你适应地点的特殊性并承认其不同的品质,你才能提供丰富性和品质。这种对种类的冲动来自1968年,个性越来越受到认可。在这个第一个住宅项目中,如果我有几种类型的窗户,这对我的承包商来说是一个挑战,10-15年后,我可以有很多变化,但不再是一个挑战,现在几乎任何事情都是可能的!

VB: Let’s go back to your residential project on Rue des Haute Formes. Was that also your attempt to break away from the anonymous character of architecture?

CP: Exactly. I tried to provide different types of dwellings with several different types of windows and balconies. I felt it was important for people to identify with their place within the complex. There was a shift. My teacher Georges Candilis taught that if you are designing a residential block, you need to provide exactly the same situation and condition to everyone. Equality was a major concern. Yes, equality is an idealist notion but you learn with architecture and urbanism, and you realize that by treating things equally you ruin everything. Equality ruins everything because east and west is different from north and south. You must provide a variety of qualities – more gardens or more openings, etc. Only if you adapt to the specificity of the place and acknowledge its different qualities will you provide richness and character. This urge for varieties came out of 1968, which exploded this thinking; individuality became more and more acknowledged. In this first residential project if I had several types of windows it was a challenge for my contractor and 10-15 years later I could have as many variations as I wanted; it was no longer a challenge. And now almost anything is possible!

卢森堡爱乐音乐厅|Luxembourg Philharmonie, Luxembourg, 2005. Image © Wade Zimmerman

VB:如果你要描述你的建筑,你会怎么描述?

CP:序曲,开幕式,不同的开放的解释,开放的,柔和的,平静的,连续性的,特定的,幸福的,个性的。

VB:你提到了普利茨克奖。 奇怪的是,在这个时候,普利兹克不再给有关个人特质的建筑师给予的奖项。

CP:即使是我们现在分享的关于我们的地球和生态的关切之情,还有公共财政的情况,这个创造性个人成就还是一个荣耀。 在我自己的工作中,我关心的是如何修复和继续建设我们的城市——如何使他们可以适合每个人。

VB: If you were to describe your architecture what words would you choose?

CP: Overture, opening, opening in different interpretations, open block, softness, pacification, continuity, site-specific, happiness, individual character.

VB: You mentioned the Pritzker Prize. Curiously, at this time the Pritzker is no longer giving its coveted prize to architects concerned with individual character.

CP: It is still a glorification of one creative individual achievement, even if it is the concern we all share now about our planet and ecology, and the situation with public money, which is lacking everywhere. In my own work, my concern is in how to repair and continue building our cities – how to make them accessible and livable for everybody.

纽约LVMH大厦|LVMH Tower, New York, 1999. Image © Nicolas Borel

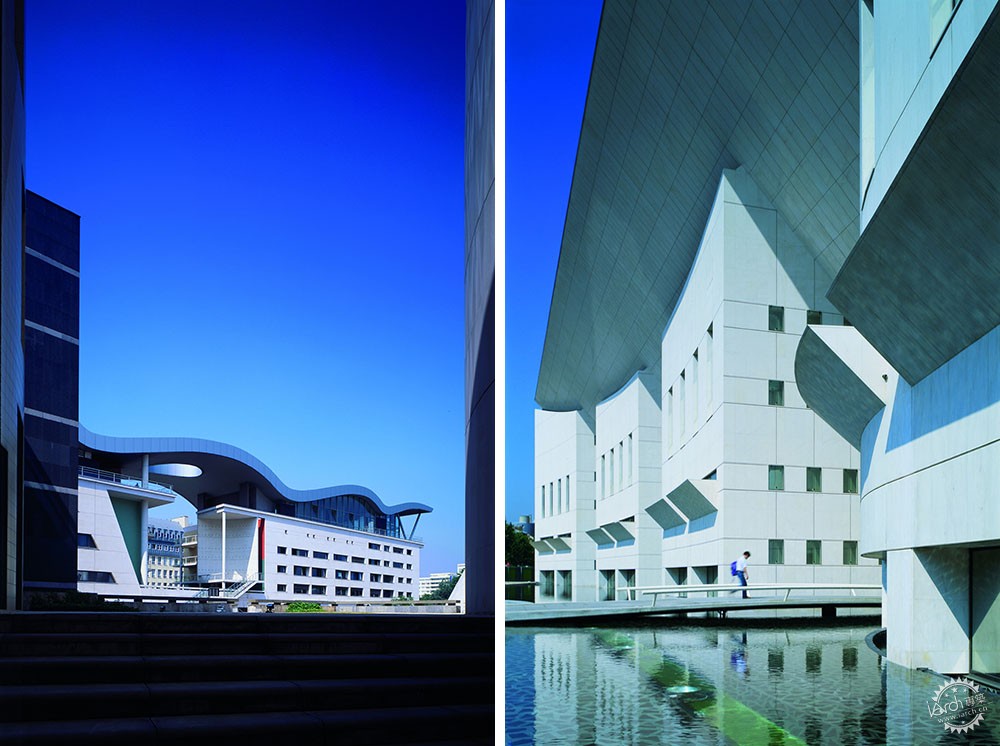

VB:然而,您将这些关注与诸如首尔的奢侈品牌Christian Dior的雕塑建筑或苏州和上海的歌剧院的雕塑建筑结合在一起。

CP:我们同时做在巴黎工作的城市居民区和经济适用房。 顺便说一下,这些项目我们在亏损,但我在这里看不到冲突。 每个项目都提供了解决技术问题或艺术表现的机会。

VB: Yet, you combine these concerns with work on such pleasure projects as a sculptural building for a luxury brand Christian Dior in Seoul or Opera houses by the Lake of Suzhou and Shanghai.

CP: We do both. And we continue working on urban neighborhoods and affordable housing here in Paris. By the way, we are losing money on these projects. But I don’t see a conflict here. Every project presents opportunities for solving technical problems or expressing artistically.

巴西Cidade Das Artes艺术馆|Cidade das Artes, Rio de Janeiro, 2013. Image © Hufton + Crow

巴西Cidade Das Artes艺术馆|Cidade das Artes, Rio de Janeiro, 2013. Image © Nelson Kon

巴西Cidade Das Artes艺术馆|Cidade das Artes, Rio de Janeiro, 2013. Image © Nelson Kon

VB:你说:“建筑的存在不能用语言描述。 在设计一个项目时,我认为在空间、形象、距离、阴影和光线等方面,作为建筑师,无法通过语言描述思想领域的工作。 我正在考虑用一些形式和数字来表达。”

CP:当我画画的时候,我不试图说出我的想法和喜好,并不总是需要说明为什么某些事物是按照设计的方式设计的。 当我让我的团队交流我的想法和开发项目时,语言变得很重要。 建筑不能简化为语言。 语言是关于沟通,但空间是关于存在,是一种原始、古老的与世界相关联的方式,并表达我们的想法。 建筑可以沟通,因为它超越了语言。

VB: You said, “The raison d'être of architecture is not to be found in language. When designing a project, I think in terms of space, figure, distance, shadow and light. As an architect, I work in an area of thought which is not accessible through language. I am thinking directly in terms of forms and figures.”

CP: When I draw or paint, I don’t try to reason my moves and preferences. It is not always necessary to tell why certain things are designed the way they are designed. Language becomes important when I involve my team to communicate my ideas and develop projects. Architecture cannot be reduced to language. Language is about communication but space is about presence, a primitive, ancient, and archaic way to relate to the world and express how we see it. Architecture can communicate because it goes beyond language.

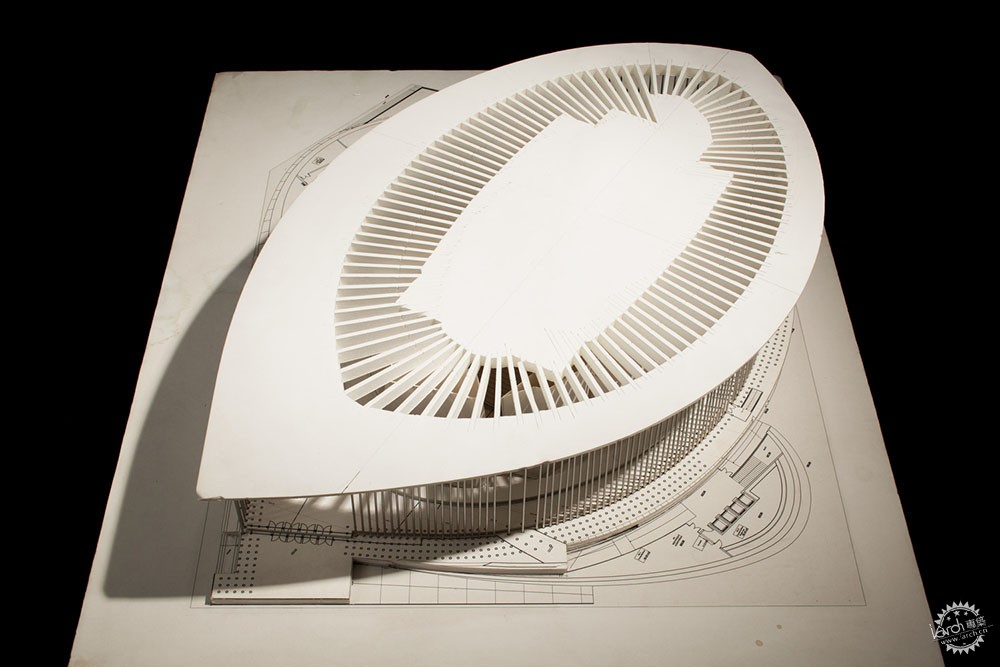

法国塞纳-马恩省水塔剖面图|Section of water tower, Seine-et-Marne, 1974. Image © Christian de Portzamparc

VLADIMIR BELOGOLOVSKY是纽约非营利策展人项目的创始人。 他曾在纽约库珀联盟(Cooper Union)担任建筑师,撰写了五本书,其中包括与名人时代的建筑师对话(DOM,2015),Harry Seidler:LIFEWORK(Rizzoli,2014)和苏联现代主义:1955-1985( TATLIN,2010)。 在他众多的展览:Anthony Ames:Casa Curutchet,La Plata,Argentina(2015)的对象型景观; 哥伦比亚:转型(美国之旅,2013-15); 哈利•塞德勒:建筑绘画(2012年以来的世界巡演); 和第11届威尼斯建筑双年展俄罗斯馆象棋游戏(2008)。 Belogolovsky是柏林建筑周刊SPEECH的美国记者,并在20多个国家的大学和博物馆讲课。

Belogolovsky的“思想之城”专栏介绍了ArchDaily的读者与来自世界各地最具创意的建筑师进行了持续的对话。 这些亲密的讨论是策展人即将到来的展览的一部分,以及2016年6月在悉尼大学首演的同名会议,思念城市展览将前往世界各地,探索不断变化的内容和设计。

VLADIMIR BELOGOLOVSKY is the founder of the New York-based non-profit Curatorial Project. Trained as an architect at Cooper Union in New York, he has written five books, including Conversations with Architects in the Age of Celebrity (DOM, 2015), Harry Seidler: LIFEWORK (Rizzoli, 2014), and Soviet Modernism: 1955-1985 (TATLIN, 2010). Among his numerous exhibitions: Anthony Ames: Object-Type Landscapes at Casa Curutchet, La Plata, Argentina (2015); Colombia: Transformed (American Tour, 2013-15); Harry Seidler: Painting Toward Architecture (world tour since 2012); and Chess Game for Russian Pavilion at the 11th Venice Architecture Biennale (2008). Belogolovsky is the American correspondent for Berlin-based architectural journal SPEECH and he has lectured at universities and museums in more than 20 countries.

Belogolovsky’s column, City of Ideas, introduces ArchDaily’s readers to his latest and ongoing conversations with the most innovative architects from around the world. These intimate discussions are a part of the curator’s upcoming exhibition with the same title which premiered at the University of Sydney in June 2016. The City of Ideas exhibition will travel to venues around the world to explore ever-evolving content and design.

巴黎音乐城|Cite de la Musique East Wing, Paris, 1995. Image © Nicolas Borel

巴黎音乐城|Cite de la Musique East Wing, Paris, 1995. Image © Nicolas Borel

巴黎音乐城|Cite de la Musique East Wing, Paris, 1995. Image © Christian de Portzamparc

卢森堡爱乐音乐厅|Luxembourg Philharmonie, Luxembourg, 2005. Image © Mathieu Faliu

卢森堡爱乐音乐厅|Luxembourg Philharmonie, Luxembourg, 2005. Image © Nicolas Borel

法国巴黎议会大厦|Palais des Congrès extension, Paris, 1999. Image © Atelier Christian de Portzamparc

法国巴黎议会大厦|Palais des Congrès extension, Paris, 1999. Image © Nicolas Borel

出处:本文译自www.archdaily.com/,转载请注明出处。

|

|